[ad_1]

A bleak edge of northern France is a strange place to listen to a homily on hope but, against all odds, you still are guaranteed to hear one here.

“People only need to have some little hope,” says the English graduate from Sudan, when I ask if he thinks he will make it across the Channel. The rain thickens, darkening the mud. I start shivering. He notices, laughs and says encouragingly, “A little hope is more than none!”

This is Rue de Judée, a ragged patch of ground on a dreary fringe of Calais. The adjacent woods and wastelands are home to men and boys from Sudan and Afghanistan. More than 100 have gathered this afternoon for a distribution of aid that includes morale-boosting mini-goalposts, a plastic cricket bat and stumps.

Although various organisations, including French and international Catholic charities, supply aid to Calais, a Union Jack might as well fly over the Rue de Judée this afternoon.

Everyone is here because the residents of the surrounding coppices long to be in Britain. The games are British. The Care4Calais charity doing the distribution is British. There is something queerly British about the way Afghan cricketers and Sudanese footballers ignore both the downpour and the police vans disgorging riot-armoured officers.

Even the police are oddly British, in that they are partly funded by UK taxpayers. Their daily raids into the scrub are the practical application of Franco-British immigration policy, which means the confiscation of tents and equipment, evicting occupants and denying people deemed illegal settlers any sense of security.

It may be the insistent November rain but the officers appear more dogged and less bullish than they did in February, when I first came to ask why so many people were risking their lives crossing the Channel in flimsy inflatable dinghies. Between January and June, at least 366 small boats made it through the 21 miles of waves, tides and shipping lanes that divide England from France. More would follow. I was astounded at the determination and the hazards involved. Why would you do it, I asked. Back then, every answer contained the most generous assessments of my homeland.

“Britain abolished slavery,” a man from Cameroon said. “British education!” cried an amused young man from Sudan. “When I have children I want them to go to school there. In the UK it is better,” he said, determinedly. A semi-circle of his friends agreed. Britain is not racist, they told me. It is a fair country, a good country. They knew people there who told them it was better.

So went the mantra. Since then, in the promised land across the water, a man has died at the Manston processing centre in Kent, where violence, squalor, overcrowding and outbreaks of scabies and diphtheria left the independent chief inspector of borders and immigration, David Neal, “speechless”. A far-right extremist has attacked a reception centre at Dover. One home secretary, Priti Patel, has tried to offshore asylum claimants to Rwanda. Her successor, Suella Braverman, who described the small boats as an “invasion” in a speech to parliament, told the Conservative party conference last month that resurrecting the policy is “my dream, it’s my obsession”.

Braverman recently signed away £63mn to pay for more police, more technology and more patrols on the beaches around Calais. It seems an apposite moment to ask the people here if any of this has made a difference to the Britain of their imaginings, or their resolve to get there.

Any who succeed will join 33,000 people who crossed the Channel in small boats between January and September this year. Any who claim asylum will join a processing queue that was 103,000 people long at the end of June, when figures were last published. The UK Home Office reports it has processed just 4 per cent of last year’s claims, granting refugee or similar status in 85 per cent of cases.

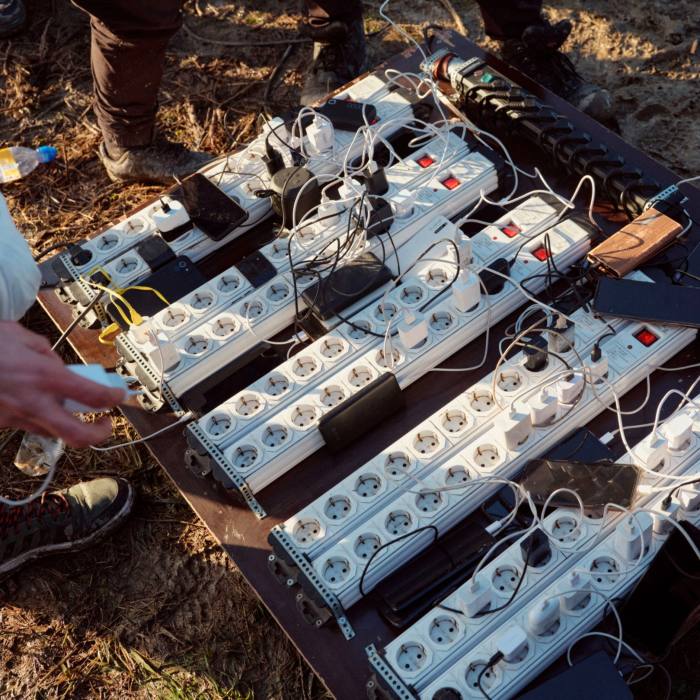

As the police set off to sweep the camps, men and boys mill around the Care4Calais volunteers, who provide them with sleeping mats and tarpaulins, tea and haircuts. The volunteers set up generators for phone-charging boards, and fold-out tables for children’s games.

Distributions like this are the only signs of kindness towards the people of the wastes, daily breaches in a painstakingly maintained hostile environment.

Although they have been doing this for years, the charities have only recently won the legal right to distribute food at fixed points — formerly the legal areas were switched at short notice, to disrupt their efforts. Even if they could be legislated away, their absence would leave the 3,000 people they estimate are sleeping rough around Calais and Dunkirk colder, hungrier and more desperate. It is hard to picture that going well. The French state makes the same calculation, endorsing one group, La Vie Active, which provides a meal a day.

I do not see the men I spoke to last time but I recognise the look among the people queueing for tea, charging their phones and playing Connect Four and cards: mostly young, warmly friendly, tracksuited and, despite the freezing rain, often flip-flopped.

One of the longest-serving charity volunteers, a veteran of two years’ work here, shakes her head. “They wear flip-flops because if their shoes get wet they will never dry.”

Almost no one I spoke to wished to be named — the veteran relies on the trust of people she calls “the guys”, who she says are wary of journalists — but, between the volunteers and the refugees, a picture of this battleground between hope and despair emerges.

The veteran is renowned in the camps and among the charities for her access to the settlements and her on-the-ground understanding of the people’s situation. She first took me around Rue de Judée and its adjacent camp, Old Lidl, named for the supermarket that once stood here, back in February.

Returning now, the dwellings strike you first, their blue tarpaulins the brightest splash in a colourless landscape. Below a motorway horizon and above a ditch, Old Lidl is a line of tents, many donated by music festivals in Britain, balanced on bits of pallets, scattered around with torn fragments, bottles, rotted trainers, cartons and toothbrushes.

Efforts are made to keep order — tins are stacked in rusty heaps, the path is clear and the cooking fires have makeshift seating. Amid acrid smoke people smile and say, “Hello!”.

The dereliction is profoundly upsetting. Civilisation seeks to separate roads, tents, wasteland, smoke, people and refuse. Here they are compacted.

At Old Lidl the men around the fires are overwhelmingly Sudanese. Along with the Eritreans camped at the site known as BMX, they are among the poorest groups. They do not have money for the boats but there are dozens of them, and so they occupy this ground because it offers access to the motorway, where Britain-bound lorries occasionally slow, and a truck parking area, which can be broken into.

“So many nights someone is injured trying to cross with the trucks. One man broke both his legs,” the veteran says. Volunteers and refugees I interviewed spoke of people beaten by police or drivers. Travelling with truck drivers earlier this year, I heard their counter stories of threats and intimidation.

“Calais is a nightmare,” says the volunteer. “It’s a trap. People arrive here normal, but so many lose their minds.” The result is a world haunted by hearsay, disappearances and uncertainties.

“On October 30 lots of people tried the boats — they launched from Sangatte,” the veteran says. “Some didn’t make it — people were in the water. One person lost his brother. The coastguard said they saved everybody but I know he was in the boat and he never came back. We went to the hospitals in Boulogne, in Calais, we went to the coastguard and checked with the police. I had to tell the family in Sudan. His mother has been crying for weeks.”

The International Organization for Migration’s records show 205 people attempting to cross the Channel have died or gone missing since 2014. The UK Home Affairs Committee’s estimate is “at least 166”. Neither includes the alleged missing person of October 30. A year after 27 people died in a single incident, marked this week in a candlelit vigil, the true numbers of the disappeared are unknown.

Some of those most likely to try the boats, the veteran says, are sleeping rough in Calais town centre. Each settlement has an unofficial name and an approximate ethnic make-up.

Old Lidl and Auchan are mostly Sudanese. Others are Old Jungle (Afghans, Iraqis, Iranians), Hospital Jungle (Afghan), and Unicorn (a mix of Ethiopians, Iranians, Pakistanis, Egyptians and Moroccans). While these are scrappy tent clusters partly hidden in thickets, Town Centre has populations of Syrians, Afghans, Yemenis, Iraqis and Iranians sleeping under bridges. It is raided frequently, but it offers access to the boats.

I ask about Albanian nationals, whose crossings have significantly increased this year. Few were seen in Calais — it seems they used other routes. Albanians have become the villains of the way this story is told in Britain: economic migrants, it is said, rushing to fill job vacancies or work for gangsters. In fact, over half of the Albanians who claimed asylum in the first half of this year received it.

The marketing of the boats and the collection of fares is organised at a distance. “The refugees who have no money do all the dirty jobs, find the people, get the money, give it to the smuggler. If anyone is caught it’s them, they go to prison, not the big boss,” says the veteran.

On the beach there is another hierarchy, she says. Those paying full fare, €2,000-plus, get a place on the boat. Poorer people pay less to go standby.

“If there’s no space, you wait, because you can only pay €800-€1,000, so you go to the beach many times and there is no space, so you wait.”

Waiting and hoping are Old Lidl’s specialities. It is hard to know whether to cheer at the resilience of the human spirit or despair at its quixotic insistence — either way, Britain in the winter of 2022 is as bright as it was in the spring in the residents’ imaginations.

“The English understand us,” the English graduate from Sudan says. “They have understanding of our history and our situation. They know about Darfur and Blue Nile province.”

I fail to contradict him. Instead I ask, “Have you heard of the economic crisis in Britain?”

“Of course! The rich nations are poorer and the poor ones are really poor,” he says.

And of course he knows about the Rwanda scheme, too. It has not deterred him. “We do not know our destiny! Only God! If someone has some hope, he will do anything,” he says.

The charity volunteers say Rwanda drove a wave of panic through the settlements in the summer. Managers at Care4Calais believe two suicides were connected to a general feeling of despair linked to the threat of deportation from Britain, along with an increased desire to get there.

“Rwanda made people want to cross faster,” the veteran says. “They didn’t care about the wind and the waves, they just wanted to go.”

“I have good reasons,” says a 26-year-old taxi driver and rapper from Sudan. A charismatic and charming man, he claims his protest song about the military regime in Khartoum provoked police raids on his home.

“In France and Italy, Africans like us cannot have good lives. People move away from you on the bus. The UK is not like this — I have my younger brother there and he says come, it is better. He wants me to look after him, so I must go as fast as possible.”

The volunteers accrue stories of people’s motivations. John Adams, who is on tea and sugar duty for Care4Calais and Calais Light, a Christian charity, says one man told him he was inspired by “Inspector Barnaby”. “It’s the title of Midsomer Murders in Germany,” Adams says. “That’s where he’d watched it and that’s why he wanted to go.”

If this seems extraordinary, it is in keeping with the mental landscape of Old Lidl. The English graduate says he is not here at all. “I don’t tell my mother I’m in the Jungle. I tell her I am in a flat. If you understand how language affects people, you don’t want your mother to worry and get ill.”

Many of the men now huddling under tarpaulins, as the rain refuses to slacken and the police trudge back to their vans, are “living in flats”, he says.

Before I even pose the “why Britain” question, the 17-year-old Afghan, who has been playing obsessively throughout the afternoon, cries, “Cricket, Cricket for England!”

He is a right arm fast bowler, and an all-rounder, judging by his controlled and fierce cover drives. At close of play he stows the equipment carefully in the charity’s van.

Standing alone, the rain soaking his hat and his jeans, is a young Sudanese web developer. “I have a masters in ICT!” he says, with an incredulous laugh at his situation. “My primary reason is language. To start in a new country with nothing is impossible if you don’t have the language. I have family in England — not close family. When I get there I will contact them and they will help.”

He does not look sure of this. He does not look sure of anything as he talks about hope and destiny and the light dies away. The volunteers pack the generators and phone-charging boards away.

“Do you know much about life in England?” I ask.

“I don’t know much about it,” he says, quietly. “I have to get there for my family,” he says, and he looks heartbroken as he speaks.

This is the biggest change between my visits. Britain remains as alluring as ever, the hope it offers undiminished, but with weather worsening and police sweeps intensifying, the damage to minds and bodies is palpable.

The veteran volunteer exudes a haunted exhaustion. “The human brain can only take so much. So much death, so much stress and death and worry. You are only thinking about the people, it gets worse, so you stay to help, and your phone rings all the time. You don’t think about the people you have helped, only the ones you haven’t, the things you didn’t have time to do.”

There is a sick man in Unicorn camp; he has medication but his condition is worsening. The veteran rings around her contacts. Messages come back — there is no bed for him, sorry, sorry . . .

Across the sea, British chancellor Jeremy Hunt is relying on a surge of migrant labour to fill 1.2mn job vacancies. “Only higher-than-expected immigration adds materially to prospects for potential output growth over the coming five years,” according to the Office for Budget Responsibility.

But no British politician will come here to explain to the information and communications technology graduate why he is the wrong kind of migrant. Instead, Britannia remains resolved to spend ever more money on breaking the spirits of people who long to give her everything they have.

Every nightmare, every hunger pang, every cough and shiver and desperate thought in the wastes of Calais tonight can be counted a British victory, if not quite the kind you would want to see beneath the Union Jack.

Horatio Clare is the author of ‘Down to the Sea in Ships: Of Ageless Oceans and Modern Men’ (Chatto & Windus)

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on Twitter

[ad_2]

Source link