In June, U.S. solar manufacturer Qcells became the second company in the world to register its solar panels with EPEAT, a labeling system that sets sustainability standards for electronics makers. By doing so, the company triggered an obscure regulation that requires federal agencies to purchase EPEAT-certified solar panels. If, say, NASA wants to build a solar farm to power a research facility, it must now purchase panels that meet EPEAT’s strict sustainability requirements — including a first-of-its-kind limit on the carbon emissions tied to solar manufacturing.

There’s just one problem: Although EPEAT launched its solar standards in 2019, as of today, there are only six EPEAT-registered solar panels on the global market. And there are currently no EPEAT-registered solar inverters, devices that convert the direct current electricity a solar panel produces to alternating current electricity, which the grid uses. That doesn’t leave a lot of choices for the federal government, or anyone else who wants to purchase sustainably-produced solar equipment.

That’s why, in October, the Department of Energy, or DOE, launched a new prize that offers up to $450,000 to U.S.-based solar panel and inverter manufacturers that achieve EPEAT certification for their products. As a new wave of domestic solar manufacturing kicks into high gear, the DOE hopes the prize will ensure that companies use efficient processes, sustainable materials, fair labor practices, and low-carbon energy.

“The fact of the matter is, not all solar [products] in their production are created equal,” said Patty Dillon, a vice president at the Global Electronics Council, the sustainable technology nonprofit that manages the EPEAT ecolabel.

Solar panels convert the sun’s rays into electricity in a process that emits no greenhouse gases, which makes them essential for fighting climate change. To achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, the International Energy Agency estimates that the world must add 630 gigawatts of new solar power annually by 2030 — up from the 135 gigawatts installed in 2020.

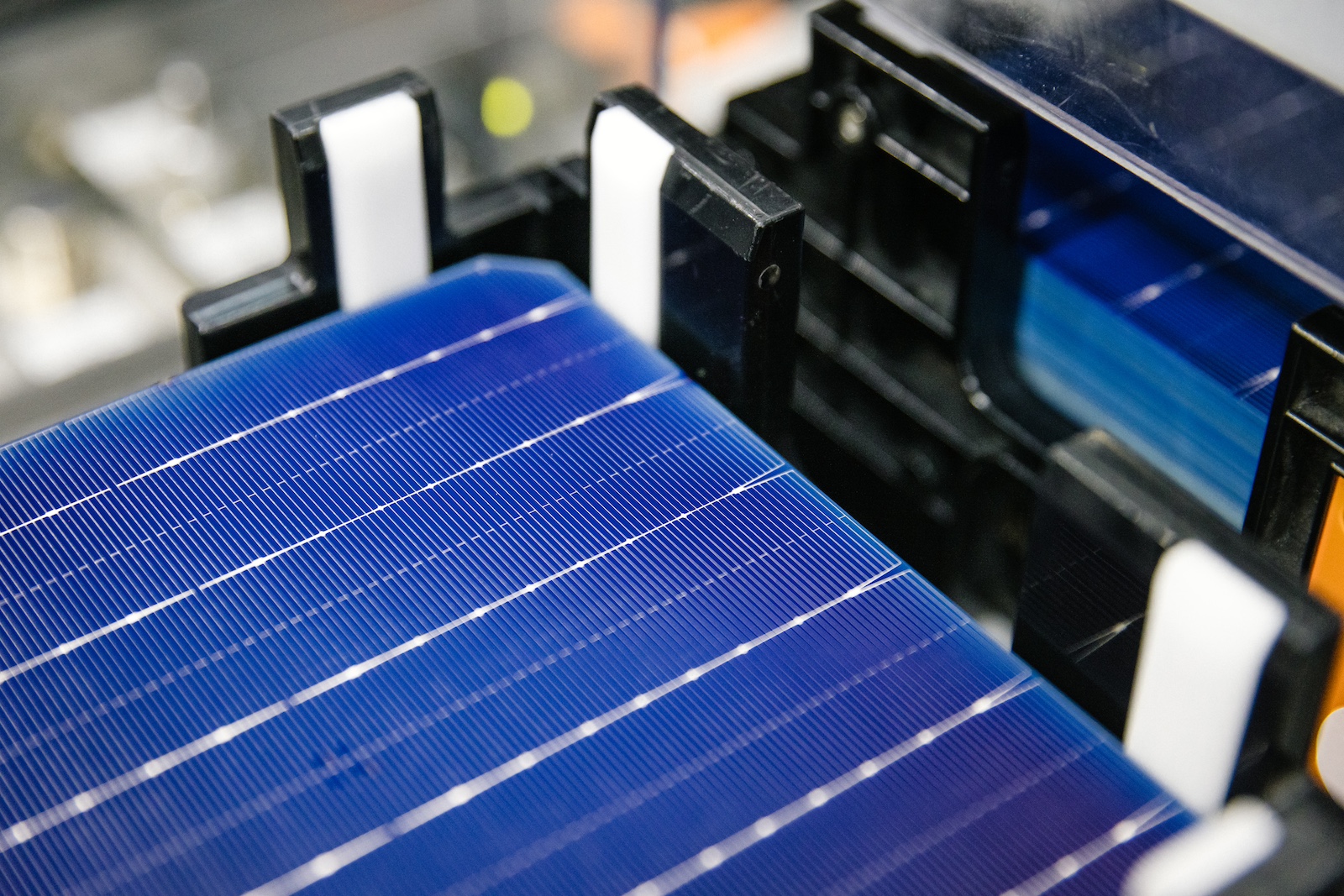

But some solar panels are more climate-friendly than others. Polysilicon, which is used to make the sunlight-harvesting cells inside silicon panels, is made using an energy-intensive process often powered by fossil fuels. The frames that hold solar panels together are made of aluminum, which is typically smelted in China using coal-powered electricity. The manufacturing processes that turn these materials into a solar panel also require energy, which can lead to more emissions. On a global level, the difference between solar panels manufactured using clean energy and those made with fossil fuels could amount to tens of billions of metric tons of carbon pollution by the middle of the 21st century.

CFOTO / Future Publishing via Getty Images

To minimize those emissions, along with other environmental challenges like the use of toxic chemicals and the disposal of solar e-waste, companies must take a hard look at their supply chains and, in some cases, engage in difficult clean-up work. The DOE’s new prize, “Promoting Registration of Inverters and Modules with Ecolabel,” or PRIME, encourages companies to do so by going through the EPEAT registration process.

“EPEAT certification enables companies to show how they have been taking the steps to have more environmentally friendly supply chains and manufacturing processes,” Becca Jones-Albertus, who directs the DOE’s solar energy technologies office, told Grist.

Solar companies seeking EPEAT registration must meet a list of criteria that span four broad themes: climate change, sustainable resource use, hazardous chemicals, and responsible supply chains. Depending on how many standards a manufacturer meets, it can receive an EPEAT Bronze, Silver, or Gold designation.

In addition, as of June, solar manufacturers registered with EPEAT are required to meet the industry’s first-ever criteria for embodied carbon, the emissions generated when a product is produced. For each kilowatt of power produced, no more than 630 kilograms of CO2 can be emitted during the production of an EPEAT-registered solar panel. The limit, Dillon says, represents about 25 percent fewer carbon emissions than the global average. Solar panels that fall below the “ultra low carbon” threshold of 400 kilograms of CO2 per kilowatt of power earn a special EPEAT Climate+ designation.

“That basically represents the best in class,” Dillon said.

It’s difficult to make a direct comparison to fossil fuel plants, since most of their emissions come from operations rather than building infrastructure. But other research has found that over their lifespan, solar plants are considerably more climate friendly, emitting roughly 50 grams of CO2 per kilowatt-hour of energy produced compared with about 1,000 grams per kilowatt-hour for coal.

Meeting EPEAT’s requirements isn’t easy, which might explain why there are only two companies — QCells and the Arizona-based First Solar — currently listed on the registry. And only two solar panels manufactured by First Solar have earned the ecolabel’s Climate+ badge. QCells, which manufactures two EPEAT-registered panels at a factory in Dalton, Georgia, spent about two years going through a “very extensive” certification process that involved collecting data across its supply chain and submitting to a third-party audit, corporate communications lead Debra DeShong told Grist.

Dustin Chambers for The Washington Post via Getty Images

“It’s not an easy task,” DeShong said. “It requires resources and it requires a will.”

Other companies may now be motivated to try. QCells’ additions to the EPEAT registry in June activated the Federal Acquisition Regulation, which requires the federal government to purchase goods that meet standards set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, except in limited circumstances where it’s impractical to do so. In the case of solar panels, that means EPEAT-registered products. The DOE’s PRIME Prize, which provides U.S. solar manufacturers $50,000 for starting the registration process and up to $100,000 per product for up to four products that complete it, offers additional incentive. Jones-Albertus told Grist that the prize was designed to “roughly offset the cost of collecting all the data and moving through the registration process.”

Solar companies “told us that they’re interested in EPEAT certification, but they haven’t gotten there yet,” Jones-Albertus said. “We’re hoping to provide incentives so that companies go through the EPEAT registration process sooner.”

Companies peering deep into their supply chains for the first time might discover they have to make some changes to meet EPEAT registration requirements. To slim down the carbon footprint of its panels, a solar manufacturer might have to switch to a low-carbon polysilicon supplier. (QCells, for instance, is purchasing polysilicon from a facility in Washington state that produces the stuff using hydropower.) Or it might decide to swap out virgin aluminum frames manufactured overseas for recycled steel ones built domestically by Origami Solar, a change that can reduce carbon emissions tied to the frame by upwards of 90 percent. To meet EPEAT’s optional recycled content criteria, a manufacturer could decide to start purchasing recycled panel glass from a company like SolarCycle.

Making these sorts of manufacturing supply chain alterations takes time and money beyond what the new DOE prize will provide. But Dillon, of the Global Electronics Council, is optimistic that more companies will start registering their products with EPEAT now that federal purchasers require it.

Erik Petersen, the chief strategy officer at Origami Solar, believes the Biden administration’s push for clean domestic manufacturing, combined with growing consumer interest in supply chain transparency, will spur more U.S. solar companies to ensure their products meet high sustainability standards.

“What’s exciting is all of these forces are coming together at the same time,” Petersen told Grist. “That really gives the industry an incentive to do the right things.”