Excerpted from Raw Deal: The Indians of the Midwest and the Theft of Native Lands by Robert Downes.

A little background: Detroit has a long history with the Indians of Michigan. It was established by the French in 1701 as a fortified trading post in the wake of 60 years of warfare between the Iroquois and the tribes of the Midwest. Dubbed “the straits” (détroit) by the French, early Fort Pontchartrain was intended as a friendly meeting ground to establish trade between various tribes who were no longer enemies. Acquired by the British during the French and Indian War, it was passed on to the United States after the American Revolution.

By the early 1800s, Detroit was still a dismal frontier outpost surrounded by swamps and far from the military power of the newborn United States. In 1812 a powerful confederation of tribes under Shawnee war chief Tecumseh gathered to reclaim their land with the help of British troops. Little did American authorities realize that the fall of Detroit was imminent…

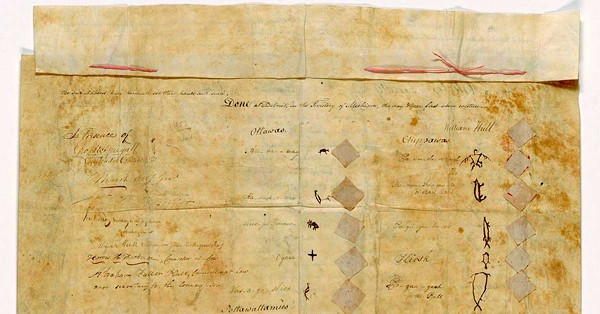

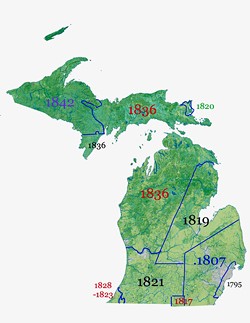

The carving of the Michigan Territory began in earnest with the Treaty of Detroit, signed in November, 1807 by 30 chieftains of the Odawa, Ojibwe, Potawatomi, and Wyandot along with Revolutionary War hero General William Hull, who was governor of the newly-created territory and its superintendent of Indian Affairs.

The treaty ceded a pie-slice of southeastern Michigan extending from present-day Toledo north to the state’s “thumb” and then west to what is now the city of Jackson. For this massive purchase of eight million acres, the U.S. Government paid just .0012 dollars per acre — a little over one-tenth of a cent — possibly the equivalent of about two-and-a-half cents per acre today. As was the case with other treaties signed with the Indians, the United States government paid pennies per acre — or less — to Indian tribes for their land and then sold the acreage at a huge profit to white settlers.

Written out in elegant script on two pages of parchment and approved by President Thomas Jefferson, the 1807 Treaty of Detroit guaranteed the Indians small parcels of land to live on within the ceded territory and provided them with “ten thousand dollars, in money, goods, implements of husbandry, or domestic animals…” The tribes were promised the services of two blacksmiths for a ten-year period. They were also guaranteed hunting and fishing rights on the ceded land, “as long as they remain the property of the United States.”

The treaty became a template for many treaties to come throughout the Midwest. It also became a template for broken promises, since Congress often fell far short of delivering the cash, supplies and services that had been agreed upon.

Robert Downes

Map shows the dates and territory taken from the Indians during the treaties starting with the 1807 Treaty of Detroit.

What could it hurt?

One might wonder why Native peoples opted to cede their ancestral lands when the threat of removal to west of the Mississippi was still more of a rumor than a reality. Simple economics forced the issue in 1807. Egged on by traders, the Indians had scoured southeastern Michigan clean of fur-bearing animals and there was nothing left to trade for muskets, kettles, blankets, tools, and other necessities except for their land. Then too, they had little understanding as to how many white settlers were waiting in the wings, or what ceding their land would actually mean. To some it may have seemed as nonsensical as the idea of ceding the sun or the wind; what could it hurt? In time, Native emissaries would travel to New York, Philadelphia, and Washington to learn to their dismay that the whites were as numerous as the leaves of the forest, but the ramifications of this onslaught may not have been anticipated by the Indians in 1807.

Not all of the Indians were happy with the treaty, however. Some of the Native signatories sided with the British soon thereafter as part of Tecumseh’s alliance in the War of 1812, while others stayed neutral, taking a wait-and-see approach as to which side would come out on top, the Brits or the Yanks.

Rebuilding Detroit

Sealing the deal in 1807 was one of the high points of Hull’s career. He had arrived in Detroit only two years earlier just after the whole town burned down as the result of sparks flying out of a baker’s pipe and igniting a pile of hay. Together with newly-arrived judge Augustus Elias Brevoort Woodward, the two masterminded the rebuilding of Detroit, with Woodward designing the streets arranged like spokes from the waterfront. From this pinnacle of achievement Hull’s career and reputation plummeted to the bottom five years later when he was duped into surrendering Detroit to a lesser force of the British and their Indian allies during the War of 1812.

The war had a number of causes. For years the British Navy had been kidnapping sailors off American merchant ships on the slimmest of pretenses, and then even from a U.S. warship, impressing them into lives of virtual slavery aboard their own ships. American trade with Europe was also suppressed amid the Napoleonic Wars, causing economic turmoil at home. Add to this, the Brits were rabble-rousing the Indians, who raided American settlements from the safety of British Canada. The administration of James Madison declared war after Britain refused to end its practice of plundering American ships. Unfortunately, news that Britain intended to end the impressment of American sailors arrived weeks after the war got underway.

Surrender at Mackinac Island

The capture of Detroit was preceded by the bloodless surrender of Mackinac Island on July 17, 1812.

In mid-July, fort commander Lieutenant Porter Hanks noticed that the normally-friendly Odawa had developed a certain “coolness.” A friendly Odawa also told him that large numbers of Indians from many tribes were gathering at the British fort on St. Joseph Island lying thirty miles to the north. Hanks dispatched Michael Dousman, the captain of the local militia company, as a “confidential person” to find out what was going on.

Dousman had paddled his canoe about 12 miles across the gray-green waters of Lake Huron when he spotted an armada of 70 war canoes flying pennants of eagle feathers and streamers of cloth and willow fronds, filled with 600 warriors painted for war. Accompanying them were 50 British soldiers aboard the schooner Caledonia and ten bateaux bearing 150 Canadian militiamen. Taken captive, he was pumped for information by British Captain Charles Roberts, whose force landed on the north end of the island at 3 a.m.

Wishing to avoid bloodshed, Captain Roberts sent Dousman to warn the residents of the town below the fort to take shelter, making him promise not to spill the beans to the American troops. Roused at 6 a.m. by Dousman knocking on their doors, the townspeople fled to a stout distillery for safety. Their flight was reported to Lt. Hanks by the post’s surgeon, who lived in town. Lt. Hanks mustered his troops and prepared to make a stand.

Meanwhile British Captain Roberts and his force made their way along a rough track across the island to the heights above the fort, setting up a 6-pounder cannon, which was capable of firing an iron ball about the size of a softball. Easily maneuvered and capable of knocking down walls, firing shrapnel or canisters full of slugs like a giant shotgun, or skipping a ball across a field of troops, the 6-pounder was the artillery of choice in battles ranging from the Revolution to the Civil War. Even so, its 870-lb. barrel and carriage of several hundred pounds hauled without the aid of horses or oxen made for a tough slog up the rough trail to the heights above the fort.

Down below, Lt. Hanks and his 61 men had seven cannon, but all of them were trained on the harbor, and in any event, their cannon could not fire uphill even if they’d been wheeled around. Nor was withstanding a siege possible, since the fort’s only well was located outside its walls. Later that day, three townspeople arrived and talked Hanks into surrendering — an easy decision, considering the odds. He and his men didn’t even know that war had been declared. As was a common practice at the time, Hanks and his men were set free by Captain Roberts after swearing a gentleman’s agreement that they would not take up arms against the British.

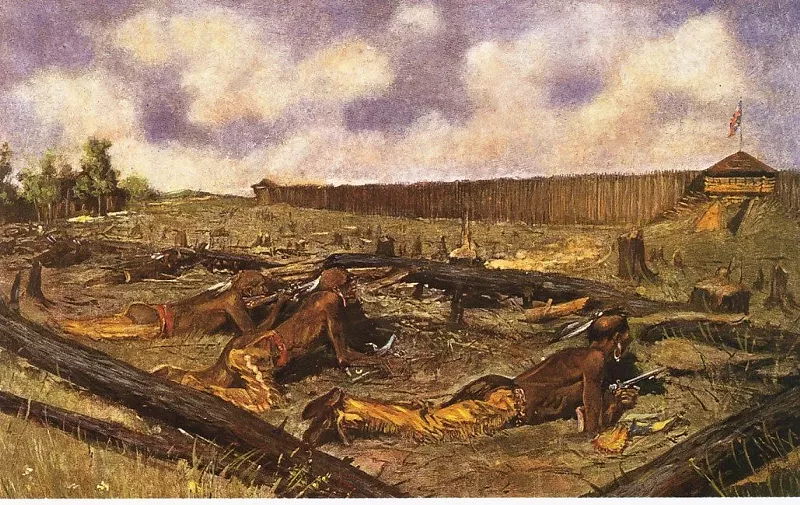

Frederic Remington, public domain

A depiction of the 1763 Siege of Fort Detroit by Frederic Remington.

Siege of Detroit

Weeks later in August, British Major General Isaac Brock laid siege to Detroit with a force of 1,300 soldiers, 600 warriors, and two gunships, bombarding the town from across the river in Canada. For his part, American General Hull had 2,500-3,000 troops and militia and 700 civilians sequestered behind Detroit’s palisaded walls. Alas, their supply lines were cut off and they were far from any hope of rescue.

Hull had accepted the order to secure Detroit with great reluctance, and then only because no other general was available. His orders included attacking the British Fort Malden at Amherstburg across the river in Canada. The American strategy called for conquering Canada in order to end Indian attacks on U.S. soil from their sanctuary beyond the border.

But Hull was the wrong man for the job. Nearly 60, he had suffered a stroke and was debilitated by additional health problems and personal tragedies. With supplies from Ohio cut off by Tecumseh’s warriors and British troops, Hull began to crack, speaking in a trembling voice and dribbling tobacco juice down his beard and clothes. Worse, 400 hand-picked men, the cream of his troops, had gone off to try re-opening the supply lines to Ohio and had elected not to return to Detroit’s defense.

Psychological warfare played a major role in the siege of Detroit. General Brock had arranged for a British courier to be captured along with a bogus document, which claimed that 5,000 Indians were preparing to attack the fort. Learning that the fort at Mackinac Island had been taken, Hull said its defeat “opened the Northern hive of Indians, and they were swarming down in every direction.” In a panic over the Indians and his blocked supply lines, he abruptly canceled the attack on Fort Malden, outraging his officers and crushing troop morale. “He is a coward and will not risque his person,” said one of his soldiers.

A good laugh

Huddled behind the log palisade of Detroit, Hull and his men watched as long lines of Shawnee war chief Tecumseh’s warriors paraded past the fort, uttering hideous war cries and gesturing with their weapons before sneaking around unseen behind a low bank of earth to repeat the charade. One can imagine the warriors had a good laugh back in their camp as the subterfuge went on.

Prior experience with Indian warfare had shown that native warriors might be content to simply plunder their foes and knock them about a bit if they surrendered, but a bloodbath was almost certain if they took losses in battle. Native war chiefs were far less cavalier about the loss of a single man compared to commanders in the Napoleonic and American Civil wars, who sent tens of thousands to their deaths in mass attacks and then slept well at night. The loss of a single warrior was devastating to his family and his band; for who then would care for his wife and children? A war chief was judged by how many men he brought home safely, perhaps even more than the victories he scored.

Of course, the slaughter of innocent non-combatants was hardly confined to that of Native warriors. Across the ocean amid the war with Napoleon, hundreds, if not thousands of unarmed Spanish citizens who refused to surrender to the British were killed by Lord Wellington’s troops at the towns of Badajoz and San Sebastian in an orgy of mass rape, murder, and arson that went on for days even while the war in America was being waged. An appalled British officer wrote that, “Men, women and children were shot in the streets for no other apparent reason than pastime; every species of outrage was publicly committed in the houses, churches and streets, and in a manner so brutal that a faithful recital would be too indecent and too shocking to humanity.”

Surrendering to the Indians in the hope of being spared was a reasonable option, and Hull would have learned that not a soul was harmed by the warriors at Fort Mackinac. Gen. Brock played on well-known fears of a massacre, advising Hull that he had little control over his Indian allies, whose blood was up. “It is far from my inclination to join in a war of extermination,” he wrote to Hull, “but you must be aware, that the numerous body of Indians who have attached themselves to my troops, will be beyond control the moment the contest commences.”

Horrified

“My God! What shall I do with these women and children!” Hull exclaimed on receiving Brock’s message. Horrified at the thought of a bloodbath, he was bamboozled into surrendering Detroit on August 16, 1812 without firing a shot or even consulting his officers.

Outnumbered two-to-one, British General Brock had nonetheless crossed the river with 330 British regulars, 400 militia, and 600 Indians. His force captured 2,500 American troops, thirty-three cannon, and the Adams brig of war, including the entire Michigan Territory. An admiring Tecumseh exclaimed, “Now this is a man!” But a man for only a short time; Brock was killed in battle at Niagara two months later.

Hull later claimed that Detroit had been running low on ammunition and cannon balls, but Brock’s troops were astonished to find more than five thousand pounds of powder and huge quantities of shot at the fort. Hull was court-martialed in 1814, convicted of cowardice and dereliction of duty, and sentenced to die by firing squad. He dodged those bullets, however, after President James Madison pardoned him in lieu of his age and service in the American Revolution.

One of the ironies of the fall of Detroit was that three days later, Hull’s nephew, Captain Isaac Hull, would capture the British warship, Guerriere while commanding the U.S.S. Constitution, sending shock waves through the mighty British Empire. Isaac Hull was hailed as a national hero, while his uncle’s reputation went “hull down.”

More information on the author can be found at robertdownes.com.