Sherry Shang could have pursued a comfortable career in media after graduating from a top university with a masters degree in journalism last June, but instead the 25-year-old headed for a tiny village in Hunan province where she enforces Covid-19 regulations and signs up locals to join the Chinese Communist party.

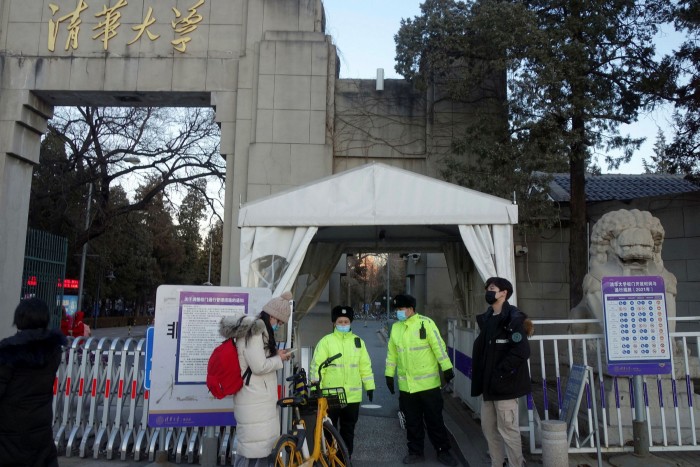

The Tsinghua University graduate had previously interned at tech titan Tencent and state broadcaster CCTV but found the work unappealing. “This job has allowed me to understand the di ceng [grassroots], to learn about real Chinese society,” she said.

Shang is just one of tens of thousands of graduates who have taken a job in China’s sprawling bureaucratic state. The new cadres are often deployed in the countryside, far from the megacities that have driven the country’s economic growth over the past few decades.

She joined an elite civil service scheme known as xuan diao or “recruit and transfer”. It takes ambitious youth from leading universities and turns them into administrators at the lowest rungs of government in townships and villages.

Applicants are recommended by their university and their local Communist party branch before sitting for an interview and written exam. After a few years as a political cadre, some graduates are fast-tracked to more senior roles with provincial and central governments.

Shang hopes to work for the Hunan provincial government after her stint in the countryside. “We [xuan diao students] can get promoted fast. I just want to do something for society, for the whole country,” she said.

Victor Shih, a professor of Chinese political economy at the University of California, San Diego, said that xuan diao was a breeding ground for Communist party leaders, especially now as the study of Marxism and ideology grows in importance in China.

“There’s a pretty high percentage of college students at elite universities who become party members in China. If the party mobilises people, there’s quite a bit of pressure to answer the party’s call,” he said.

A recruitment document for xuan diao hopefuls in Shanxi province stipulates that applicants must have “good political quality, a sense of political mission and lofty aspirations [and be] willing to serve the country and the people”.

While some students become village cadres out of a sense of duty and conviction, many others have chosen to embrace the “iron rice bowl” of secure state employment as China’s economy staggers under the burden of its strict zero-Covid mandate and slowing growth.

The job market is particularly tough for young people, with youth unemployment reaching 18.4 per cent, according to data from Japanese investment bank Nomura released in April.

“We’re seeing a larger number of students interested in these di ceng positions, even at the best universities in China,” said Shih. “You wouldn’t see the kinds of numbers we see this year without the job market being so poor.”

Katherine, another recent masters graduate who did not want to give her surname, struggled to find a job in the private sector and was relieved when she was recommended for the xuan diao programme.

“I felt excited to the point of tears to be accepted,” she said. “We’re from Tsinghua University, but when we apply to internet companies or media, there are so many students competing for just one position.”

This summer, 10.76mn students received their diplomas, the highest number in modern Chinese history, and a record 2mn graduates have applied to take government entrance exams, according to data analytics firm MyCOS.

The cadres are a bit like America’s “Peace Corps volunteers with executive powers”, said Shih of the University of California.

Katherine, who admitted that her new work was both repetitive and sometimes stressful, will eventually be sent to a rural area outside Beijing, where she expects to help farmers with ecommerce initiatives. According to MyCOS, her salary of about Rmb10,000 ($1,500) per month is significantly higher than the average starting wage of Rmb5,833 for graduates.

Some analysts said the scheme echoed the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s, when many young people from urban areas were “sent down” to live among rural communities. They included Xi Jinping, the Chinese president.

“This programme by the party-state to attract top students is more focused on the ideological correctness of the students,” said Mary Gallagher, a professor of political science at the University of Michigan.

“It also puts great emphasis on earning the experience and hard work that Xi Jinping has tried to encourage among the bureaucracy.”

One graduate with a PhD in public policy from a top university has begun his xuan diao training before being deployed to a rural county outside Shanghai next month.

The 27-year-old, who declined to be named, said he felt lucky to be accepted into the programme amid such fierce competition. “The Chinese think that going into government is a good job. The income is stable, the position is nice,” he said.

“But if I had majored in economics, I could have worked in the private sector. That’s where they actually create money.”