The sun is not yet up when Boots O’Neal starts his workday. As the 89-year-old cowboy readies his mount in the predawn quiet, he stuffs his hands into well-worn leather gloves. His dark chaps are decorated with fringe, a slight sheen on the right hip where his nylon rope has polished the leather over the years. He pulls down his silverbelly hat and grunts his way onto the saddle, planting his tall-topped boots in the stirrups. The horse he’s riding today is a dark sorrel named Cool. Together they wait, as the cowboy saying goes, just “cryin’ for daylight.”

This morning’s chore: Boots and three of his Stetsoned coworkers must round up some two dozen bulls scattered across a vast grazing pasture, drive them to a set of pens about a mile away, and load the one-ton beeves into a livestock trailer so they can be hauled to another division of the Four Sixes, the legendary West Texas ranch that sprawls across 260,000 acres.

As the cool blue light warms to an orange glow, the four riders trot north in a single column. Save for a radio tower blinking red to the south, the horizon is empty in every direction, just a big bowl of grass and sky. Out in the pasture, the men fan out among the hulking black bodies of the bulls. Boots looks more at ease astride his horse than he does afoot. He clutches the reins between his right thumb and index finger, his grip gentle and sure, as if he were holding a pencil. Working as a team, the cowboys cut a few head at a time out of the larger herd. Soon, nearly thirty Angus bulls are jogging toward the corrals like schoolchildren lining up for lunch. When a few start to stray, Boots lopes out to cut them off. “Ay, toro!” he calls as he and Cool push them back toward the others.

To an outsider, this might feel like a scene straight out of Lonesome Dove. For Boots, this is Tuesday morning. He’s repeated this task countless times—his career began during the Truman administration and has now spanned seven decades—but if given the chance to be doing anything on earth, this is what he would choose every time. That he’s been able to do it for so long makes him, to borrow a classic Boots-ism, “luckier than a two-peckered goat.”

Some years ago, Boots bought a lotto ticket with a possible payout of $90 million. His cowboy companions asked what he’d do if he won. When Boots failed to come up with anything, his wife, Nelda, answered for him: “He’d go to the barn and saddle up the next morning.”

Nelda knew her husband best. “If I was a little down or flusterated”—another Boots-ism—“or had some problem, Nelda used to tell me, ‘You need to just saddle up this evening and pull out down the creek.’ And when I’d get back, I’d be in good shape.”

These were among the tales Boots unspooled when I visited him at the Four Sixes in March. He’d canceled our first scheduled meeting a week earlier because he’d hurt his foot loading a trailer. As he saw it, the injury was no cause for complaint. “That foot swelled up to where you couldn’t hardly put a sock on it, but I could sit out here on the porch and see the horses come in ever’ morning, and that’s what’s important to me.” Still, he asked me to wait a while because he didn’t want to do the interview unless he could be horseback.

“There’s not very many people in the world who love their job,” Boots and Nelda’s daughter, Lauri Colbert, told me later. “I mean, people might like their job, they might tolerate it, but he loves it. When they give him the weekend off, he’s kind of mad about it.”

This devotion to his craft, coupled with the deep knowledge of ranching he’s accumulated over a stunningly long career—possibly longer than any cowpuncher alive—has propelled Boots to a level of fame practically unheard of for a working cowboy. He’s been inducted into just about every cowpoke hall of fame there is, and one could easily fill an entire Western art museum with nothing but paintings, sketches, and photographs of Boots.

Of course, part of his celebrity stems from the Four Sixes itself. Founded in 1870, when Samuel Burk Burnett purchased a hundred head of cattle marked with a “6666” brand (the origin of the brand is unknown), the Sixes is now one of the state’s most well-known ranches. It actually spans two disparate properties in the Panhandle and the Rolling Plains and is headquartered roughly halfway between Amarillo and Fort Worth, near Guthrie. This small community, population 151, made up almost entirely of ranch employees and their families, is where Boots has lived and worked for the past 32 years.

Agrarian types have long been familiar with the Four Sixes’ history of producing quality Angus beef as well as the innovative breeding programs that have yielded some of the finest quarter horses in America. But in recent years, the ranch has become a household name even among city slickers. It plays a key role in the latest season of TV’s most popular show, Yellowstone. Taylor Sheridan, the show’s cocreator, recently purchased the spread along with his business partners, and a spinoff series set on the Sixes is currently in development.

Despite the recent Hollywood attention, working cowboys and cattle are still the heart of the Sixes operation. And Boots has become the most iconic figure of the already iconic brand. Not that it’s gone to his head.

That March morning, after he and the cowboys finish loading the bulls, there’s plenty more to do: feed to deliver to cows miles away, in another part of the ranch; stock ponds to check; just-born calves and their mamas to mind. It’s a full day, yet Boots tells me I’ve actually caught them in a bit of a lull; the real work will pick up in a few weeks, during spring branding. He seems reluctant to quit when the chores are done, telling me, as he retreats to his bunkhouse for the evening, “I’ll go to sleep lookin’ forward to doin’ it again tomorrow.”

Left: Boots with a horse named Playboy. Photograph by Bryan Schutmaat

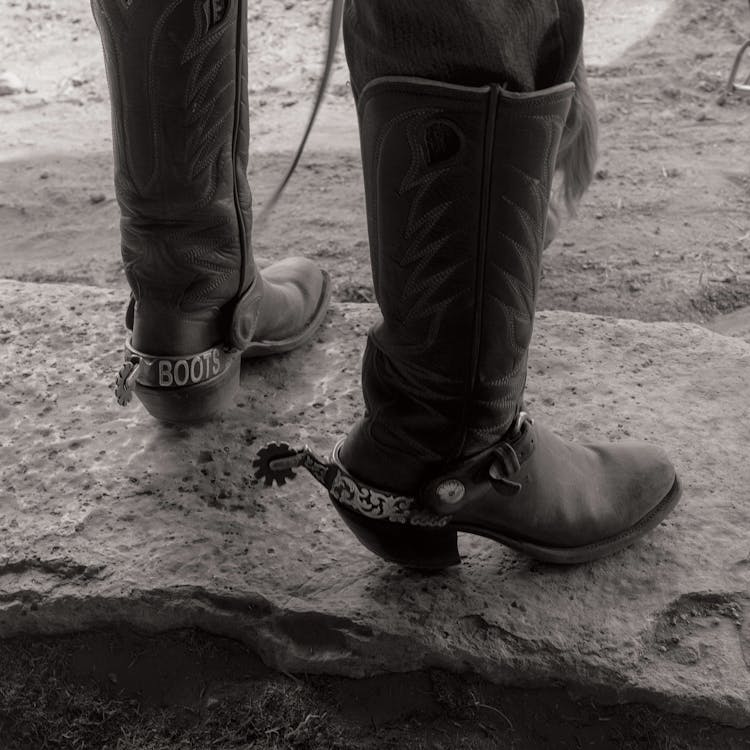

Top: A shot of Boots’s custom silver spurs, embossed with his name. Photograph by Bryan Schutmaat

So many Four Sixes visitors ask about Boots that a few of the workers at the ranch’s vet clinic made a pamphlet with a brief biography and some Boots trivia. (Favorite thing: Association with cowboys and ranching people. Second favorite thing: Western dancing. Favorite food: Beef.)

I was handed one of these flyers during a tour Boots gave me the day before the morning roundup. Wherever we went, folks stopped what they were doing to say hi. Between the stallion barn, the vet clinic, and the mess hall, we met no fewer than thirty people, and Boots hailed each of them by name, from the veterinarians and their interns to the stall muckers. He occasionally slipped into Spanish to greet some of the ranch’s forty-plus hired hands. At one point, we ran into an old colleague. “Tom Curtin, gosh a’ziggety!” Boots exclaimed. “I haven’t seen you in thirty years!”

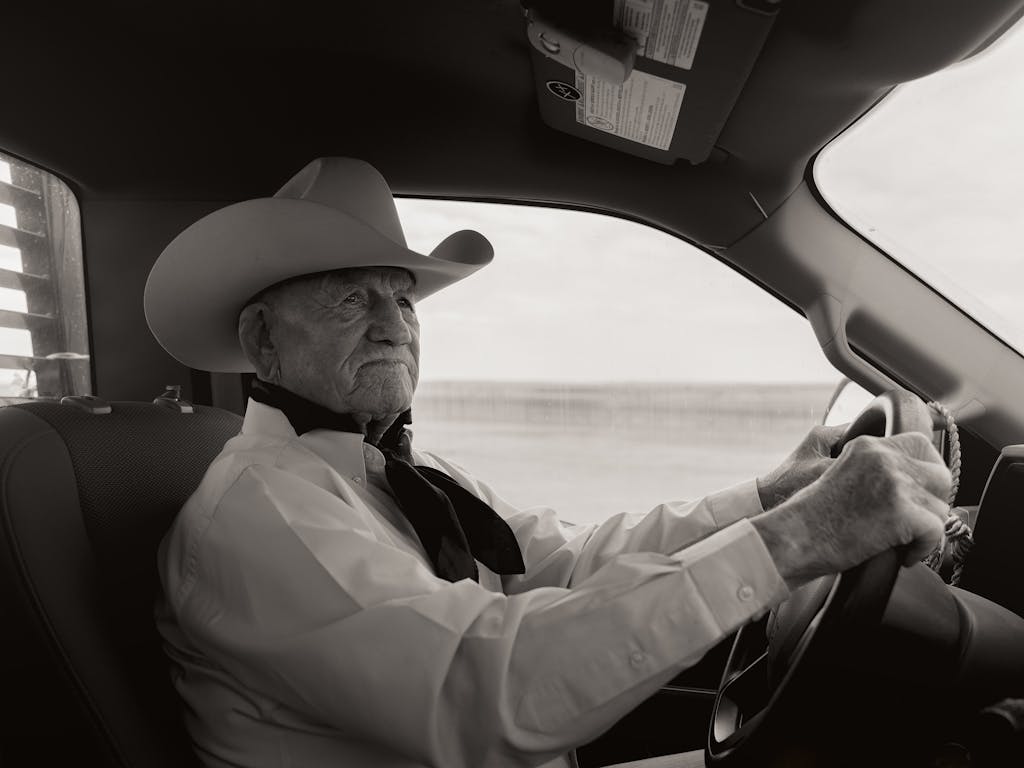

That afternoon, we loaded into Boots’s pickup, one of the many cherry-red F-350s that the ranch orders from Ford. Boots has customized his: he removed the headrests to accommodate his cowboy hat. We pulled up at a covered round corral where four cowboys were just about to start saddle-breaking a group of two-year-old horses. “Howdy, Bootsy!” the men called out as we approached.

Boots pointed at the wild ponies. “You gonna try to hem one up?” he asked the men.

True Burson, the 31-year-old wagon boss who oversees many parts of the operation, nodded as he readied his rope. “Gonna take ’em outside today. Wish they’d cut the wind off.”

These four horses had spent their entire young lives running free and untouched on the Four Sixes. Now it was time to learn to work—if they could be caught. The cowboys entered the corral, three on foot and one on horseback. The spooked horses ran. Their hooves churning the dirt, they became flashes of rust red swirling through the dust. Standing calmly in the center, True tossed a perfectly aimed Houlihan loop and caught one of the stampeding broncs by the neck. “Sure was purdy!” one of the cowboys complimented him. True repeated the motion three more times until each horse was subdued.

Boots leaned against the fence, his pale blue eyes taking in the scene. For a moment, he seemed far away. “I used to rope everything that run in front of me,” he said. “But now it’s extra duty for me just swinging a rope. I roped these horses like he’s roping them for thirty years.”

Cowboying has always been a young person’s game. The physical demands of the job take a toll: busted bones, warped fingers, stiffened gaits. Mounting health bills are compounded by relatively meager pay—the average cowboy earns around $30,000 a year, which doesn’t leave much for retirement. By their early forties, most cowpunchers will have taken on a managerial role, struck out on their own, or left the profession entirely. According to Boots, the oldest cowboy to ever be on the payroll at the Sixes was in his mid-seventies. “I’ve never known but one other man [that was older], and that was a feller named Tom Blasingame.” He was 91 when he died, in 1989, while still on the job at the JA Ranch, a historic spread in Palo Duro Canyon. His fellow cowboys found him lying in a pasture with his arms folded across his chest, his horse still saddled nearby.

Though Boots can no longer rope or stomp broncs like he once did, he still performs many of the tasks necessary to keep the ranch running, from feeding cattle to helping with roundups and branding. Plus, he’s proven an invaluable asset to Joe Leathers, the ranch manager, who consults with Boots about everything from range management to handling large herds.

With the dust mostly settled in the corral, the cowboys clucked and talked softly to soothe the horses as they slowly slipped a halter, then a blanket, and finally a saddle onto each.

“Horses are gentler now everywhere than they used to be,” Boots said. “The horses that we broke, at this stage they’d kick you or bite you if they could get a shot at you.” He explained why the cowboys have a vested interest in training these young broncs despite the trouble. Once a horse is considered saddle-broke, it is taken into the cowboy’s “mount,” a relationship that will likely stretch until the end of one or the other’s life.

At the Sixes, most of the cowboys’ mounts comprise seven to nine horses, which they rotate among throughout the workday, depending on the task. These new broncs will eventually replace a horse lost to injury, sickness, or old age. Though a cowboy doesn’t own the animal, that horse essentially belongs to him. “After you break him and take him into your mount, it would be very unorthodox for anybody to catch that horse and ride him,” Boots said. “Even the owners would ask you if it was all right to ride him.”

As the cowboys eased onto the backs of the horses for the first time, Boots’s excitement grew. “Them are looking mighty good, cowboys!” he hollered. The men made several laps inside the corral; then they opened the gate and headed out to try their fresh broncs in open pasture. As they filed past us, one called out, “See ya in the fall, if I see ya at all.”

“Hang on tight,” Boots told them. “And if you don’t make it back, I’ll tell ’em which way you went.”

When I asked Boots about some of the horse wrecks he’s been in, flashes of silver showed in his smile. He doffed his hat, turned around, and pointed to the white sickle-shaped line that curved up his scalp. “Can you see a scar right there on the back of my head? A horse bucked me off and kicked me in the head in 1950.”

He was just seventeen years old. Things didn’t get much easier from there. He’s had a few horses fall on him and some big steers smash him up. He’s broken ribs and both legs. There have been too many injuries to readily recall. About a decade ago—or maybe it was two—a steer collided

with his horse and wrenched his foot backward in the stirrup. “I could hear the bones break,” Boots said. “When I got out of the corral, I rode out and told the boys to help me hold that horse and catch me when I stepped down. They carried me to the hospital, cut that boot off. Of course, they x-rayed it and done surgery and put pins in from both sides.”

That injury might’ve slipped his memory, but the week just prior to our meeting, when he went in for an X-ray after hurting his foot, the doctor told him, “It’s not broke, but that thing is full of steel pins.” Boots was surprised. “Oh, I’d forgotten that, doc!”

But nothing came close to the morning in May 2014 when cowboying nearly cost him his life. He told me the story while we were parked on a hill overlooking rolling pastures mostly cleared of brush. Clumps of Black Angus grazed on grass in desperate need of rain. It was calving season, and a few coyotes hung around the edges of the herd, hoping for a quick, protein-rich meal of afterbirth. Boots pointed to the western horizon. About a mile in that direction is where the cowboys found him that morning eight years ago.

They’d realized something was wrong when Boots’s horse returned to the stable with an empty saddle. Several cowboys, including the ranch manager Leathers, went hunting for him. Boots was unconscious when they discovered him lying in the dirt. Best he can remember, he’d been on his horse driving the remuda back toward the corrals. “Them horses boogered, and my horse just blowed up and bucked me off right quick. Really stomped me up.” Boots was in bad shape and in far too much pain to be loaded into a pickup. “I just told them, ‘I can’t.’ I was really hurting. I told the boss, ‘Leave me here. I’ve had a pretty good life, and I don’t want to be moved.’ Joe said, ‘We ain’t going to leave you here.’ ’’

A medevac helicopter was called in and landed right there in the field. Boots was in and out of consciousness, but he recalls that on the flight to Lubbock, one of the medics radioed ahead to the hospital: “We’re coming with one that may not make it.”

At four that afternoon, his daughter, Lauri, got a call from Reggie Hatfield, who was wagon boss at the time. “I didn’t really understand at first how bad it was,” she said. Then Reggie put an EMT on the phone. Lauri asked him if she needed to go to the hospital. “Yeah,” he said, “you need to come.”

Boots had broken twelve ribs—one had punctured a lung. He had a fractured vertebra in his back, and the lower lobe of his brain was bruised and bleeding. Lauri wondered if this was the beginning of the end. But Boots wasn’t done yet. Lauri stayed by his side as, day after day, he got stronger. He was released after seventeen days. Just six weeks later, he was back in the saddle.

Boots was already well known and respected among cowboys, but his miraculous comeback pushed him into the realm of legend.

Left: A shelf inside Boots’s Four Sixes apartment. Photograph by Bryan Schutmaat

Top: On display in his ranch apartment: the Ranching Heritage Association’s Working Cowboy Award, which was specifically created to honor Boots. Photograph by Bryan Schutmaat

Cowboying was his birthright. Billy Milton O’Neal—his given name—grew up on the Mel B. Davis Ranch, in the Panhandle. An elementary school bus driver gave him the nickname “Little Boots,” a nod to his cowboy father, who was also called Boots. Little Boots was the eldest of eight and a child of the Depression; he grew up without electricity or indoor plumbing. In 1946, when he was thirteen, he and his brother Wes rode home one evening to discover smoke streaming out of the windows of their home. No one was hurt, but the local paper put the devastation simply: “The house was completely destroyed, without one article being saved.”

By then, Boots was already helping his dad on the ranch, but he knew he had to bring in some money of his own. He landed his first cowboying gig at sixteen. He and Wes spent one fall breaking twenty broncs for the nearby RO Ranch. At $20 per head, they pocketed $200 apiece (about $2,400 today). Boots was hooked. After his sophomore year, he quit school to hire on with the JA Ranch, which was cofounded by cattleman and Texas Ranger Charles Goodnight.

In those days, cowboys would often spend two-month stretches camping out with the chuck wagon wherever the crew was working. His third day on the job, Boots was given the grunt task of driving the wagon that carried all the bedrolls. While crossing the Prairie Dog Town Fork of the Red River, Boots attempted to roll a Bull Durham cigarette. He dropped one of the reins, and the two old bucking horses pulling the wagon took off, sending Boots and all the cowboys’ sleeping gear into the muddy river. Boots’s career could’ve been cut short right there, but the wagon boss kept him on, even though the cowboys grumbled about their soggy beds.

He spent the next four years doing what most young cowboys did at the time: he drifted, making the rounds from one large outfit to another—the Matador Ranch back to the JA and out to New Mexico at the Bell Ranch. In 1953 he was drafted into the Army and shipped off to Korea. Some of his fellow soldiers had a tough time adjusting to living outside and spending every night on the ground. Boots thrived and left the service two years later a sergeant.

West Texas was hard hit by drought when Boots returned home—not the best time for a cowboy to be searching for work—but he managed to hire on at the W. T. Waggoner Ranch, near Vernon, where he had worked before being drafted. (A few years later, his brother Wes would join him, and a few years after that, their brother Joe followed. Both would end up working the ranch for more than fifty years each.) At the time, the Waggoner was a massive operation: 225 horses in the remuda to work 14,000 head of cattle spread across eight hundred sections, a total of more than 500,000 acres. Cowboying was still done much as it had been for the past fifty years. The men camped out at the wagon year-round and worked seven days a week. But big changes were on the horizon.

“They started getting electricity out on these ranches in the country,” Boots said. “They started putting bathrooms in the house, got TV in the sixties. Had them little thirteen-inch black-and-white ones. I remember the first one I ever seen: one of the cowboys invited me down to his house, said we’d cook some calf fries and drink some beer and watch Cheyenne. It was a western on there. There was an ol’ boy that went with me, and he wanted to go back the next day and see it again. That cowboy told him, ‘It just comes on once a week!’ ”

The ubiquity of pickup trucks and gooseneck trailers were also transforming the way cowboys worked. Add the ongoing drought and a weak cattle market, and many of the once-sprawling ranches were downsizing. Boots decided to make a career change. In 1960 he went to work for the Texas and Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association as a field inspector. Now a licensed peace officer, he was tasked with hunting cattle thieves and checking brands at livestock sales. That’s when he met Nelda Young.

Boots clearly remembers the day he went to view the Cottle County brand book (a record of registered brands and their owners) at the yellow-brick courthouse, in Paducah. There, working in the office, was a trim, dark-haired woman. “I knew a lady who was assistant county clerk, and I walked over there and asked her who that was.” The clerk introduced them, and the two hit it off, despite an almost eleven-year age difference—Boots was just shy of thirty; she was nineteen. “The first time we went anywhere, we went to an ice cream supper out at the Triangle Ranch.” Three months later, in November 1962, they were married.

As a field inspector, Boots patrolled some twenty counties in a nice car. He wore good clothes. The job provided what most would consider a better life, but it wasn’t his true calling. One day, after inspecting a shipment of cattle on the Sixes, he stayed for dinner at the chuck wagon. Later, as he sped toward the highway, the cowboys mounted back up to ride. He knew he’d rather be with them. Boots turned over his badge in 1965 and went back to work for Waggoner Ranch, where he’d stay for the next eighteen years.

Shortly after, Boots and Nelda had their only child, Lauri. Growing up on one of the biggest spreads in Texas, Lauri never romanticized her father’s profession. “Cowboys lived in the bunkhouse that was part of our house,” she said. “They ate breakfast and lunch with us every day. They were around all the time. So I never thought, ‘Oh, he’s a cowboy.’ I mean, that somebody else’s dad wore a suit all the time never crossed my mind.”

For her part, Nelda did not share her husband’s enthusiasm for the cowboy life. “She was real ladylike,” Boots told me about Nelda. “Never was Western. Lived on these two ranches all her married life, but she just never did get into punching cows.” She wouldn’t let him buy her boots and wouldn’t wear a hat. “We had trouble over it,” Boots said, “because she loved to be in town or with people. She liked to have flowers and keep the lawn, and I didn’t like to do nothing like that. I just liked to ride.” Boots never played golf or hunted or fished. “I never did have no hobbies, all my life. All the time, when I had some time off or some slack, why, I wanted to ride somewhere with somebody.”

After branding some 10,000 head of cattle at the Waggoner, he’d have three weeks of vacation. So he’d head to the O RO Ranch, an old-school outfit in

Arizona, to work some more, just for fun. But this wasn’t Nelda’s idea of a good time. “We always took great vacations when I was younger, but then we always took separate vacations as well,” Lauri told me. The three of them would often do something together, but then Boots would peel off for Arizona while Lauri and Nelda headed to Denver to visit relatives. Once, the whole family stopped in Arizona to check out the O RO Ranch. Lauri and Nelda peeked into the bunkhouse, which had a woodstove and not much else. “Very primitive, very primitive,” Lauri recalled. Nelda started crying. “She was just so devastated that, you know, this is where he loved to be so much.”

Despite their city mouse–cowboy mouse dispositions, Boots and Nelda were happy together. Perhaps more than anywhere else, they found common ground on the dance floor. They would dance to country music, waltzes, and rags, and they loved to two-step. Besides, dancing gave Nelda an excuse to dress up.

One night in the sixties, they went to a gathering in a small ranching community. “They were playing a waltz as we stepped in the door. I said, ‘Let’s just get in that.’ And we waltzed. When the waltz was over, we was over by the men’s room. I told her, ‘I need to go in there. Go find us a table, and I’ll be out in a minute.’ Well, when I come out, she’s standing there in the middle of the floor. She said, ‘All right, smarty, that was a waltz contest, and we’re in a waltz-off with this couple standing out there.’ And I said, ‘Well, let’s just be real smooth and not try to be fancy and not make any mistakes.’ And we won it. Didn’t even know we was in it. It paid ten dollars. I donated it to the band.”

Eventually, Boots was promoted to foreman at the Waggoner, a position he held for eight years. But he never did feel right in upper management—he was frustrated spending more time in a pickup than in a saddle. In the early eighties, he resigned and went back to being a regular cowpuncher.

He and Nelda moved in 1986 to Vernon, about seventy miles northeast of Guthrie. For the first time, they purchased a home of their own. “That was a really big deal for both of them,” said Lauri, who’d gone off to college by then. “My mother loved to decorate, but they had always lived in ranch houses, and you couldn’t paint the rooms or do anything to them.” Nelda found work at the Waggoner National Bank, and Boots went into business with a few cattle of his own.

This might have been where Boots and Nelda spent the rest of their days, but then the Four Sixes came calling. It was one of the few big West Texas outfits Boots had yet to work for. In 1990 the ranch was looking for a seasoned hand who could also help with security issues involving missing cattle. Given his background as a field inspector, Boots was a perfect fit. The owner of the Sixes, the heiress and Cowgirl Hall of Famer Anne Marion, even got involved in recruiting him.

Nelda wasn’t so sure. She liked her life in Vernon. “Just two years,” Boots pleaded with her. She agreed to go to Guthrie, but they kept the house in Vernon, so Nelda could visit the town whenever she pleased.

Boots quickly made his mark at the Sixes, distinguishing himself even among a roster of great cowboys. He became good friends with Marion, whom he still refers to as “Miss Anne.” Those two years he promised Nelda turned into two more and then a couple more, until 1996, when Lauri and her husband, Darrell, who had settled in Vernon, had their daughter, Rachel. “My mom wanted to come home and be close to the grandbaby,” Lauri said. “And so she told Dad, ‘I’m going back. You stay as long as you want to.’ ”

Nelda returned to Vernon, where she got her old job back at the bank, and Boots moved into the Sixes bunkhouse. “Most marriages, that wouldn’t be a good situation, but for my mom and dad, it was great. Dad would come home on Friday night and go to church with us and then go back to Guthrie on Sunday afternoon. That was a really happy time for them because they were both doing what they wanted.”

Those good times lasted for a decade. Then, in 2006, Nelda was diagnosed with colon and liver cancer. She died in October of that year. Boots and Lauri endowed a scholarship in her name at Vernon College, where she’d worked her last few years. On her headstone, Boots had inscribed her name, birth date, death date, and right beneath, “She had class.”

After Nelda’s death, Boots kept doing what he’s always done—he kept working. That same year, he appeared in the IMAX movie Ride Around the World, which featured cowboys and horsemen from Patagonia to Morocco. In one scene, the Four Sixes cowboys are separating calves for branding. One starts to run, but Boots throws a quick loop to catch the calf before it can slip past them. Even at 72, he makes it appear effortless.

One afternoon, as we drove around the Four Sixes dropping off feed for the cattle, I asked Boots what set him apart from other working cowboys. He grew quiet.

“Really, I don’t know how to answer that question,” he said. “I’ve been recognized among the men as knowing cattle well and how to handle big herds. But there’ve been a bunch of them kind of fellers. Every crew I’ve ever worked with, there’s been somebody that I thought could rope better than I could or ride better than I could. I have never thought of myself in any way as being super.”

Boots embodies much of what is admirable in the working cowboy, traits that pop culture has long distorted, ever since dime novels recast the drudgery of driving cattle up the trail as epic adventures with more gunfights than long nights caring for vulnerable livestock. In fact, it is not so much swagger or rugged individualism that defines the working cowboy as humility and willingness to work, day in and day out, as part of a team. A cowboy’s ability to endure whatever nature throws at him, what might be mistaken for machismo, is matched by a deep reverence for animals and the land. “So many people think cowboys are rough,” Boots told me, “that they raise Cain when they get to town and get drunk and rowdy and loud. But some of the finest gentlemen that I’ve ever met are quiet, soft-spoken fellers that’ve punched cows all their lives.”

Boots has never taken to the spotlight, and the attention he’s received still puzzles him. He was candid when I asked if he’d grown weary of talking to reporters like myself. “Yeah,” he said. “I really don’t enjoy doing these, and I’ve told Joe Leathers that if people call and want to interview me, tell them I’m not doing it, because I don’t feel like I’m good at this, and I don’t . . . you know, I haven’t got a very good education.”

Lauri told me she thinks this article will be his last. “Even though he sometimes enjoys the fame and the accolades, he tells me ‘I don’t understand this. I have a ninth grade education.’ He’s very humbled by it all. Why him? He asks me that all the time.”

But you don’t have to hang around Boots for long to understand why he’s so beloved, which ultimately has little to do with his horsemanship or ability with a rope. When I stopped by the Supply House, the only store in Guthrie, Ellie Brandon, who’s twenty years old, was working the register. We got to chatting about Boots. “Every time I talk to him, he always has a huge smile on his face,” she said. She was relatively new to town, and at first Boots had trouble remembering her name. One day he told her, “Well, I wrote your name on a sticky note and put it on the visor of my truck. Every time before I go in the store, I look at it.”

“He’s just so intentional,” Ellie said. “He cares about people so much.”

For all the stories that have been written heralding the “last cowboys,” Boots is excited about the future of his trade. He says that working and living conditions are better than ever for an upstart cowpoke. Like the broncs, the cowboys have also settled down some. There are fewer drifting, single bachelors and many more family men—as well as women. “Now I get aggravated because they haven’t slept on the ground and they haven’t stayed two months out here in a camp with some ol’ boy eating sourdough bread and cooking supper on a woodstove,” Boots said. “But there are good cowboys now, and there always will be.”

Before I left the Four Sixes, Boots was kind enough to show me around his home. After Nelda died, Miss Anne had wanted to make him more comfortable, so she converted two rooms of the bunkhouse into a wing for Boots. She had it carpeted and furnished it herself. Boots remarked to one of the younger cowboys who was helping unload the furniture, “Jackson, I hope you see what can happen if you work hard and make a good hand for yourself.” To which Miss Anne quipped, “Work hard? Hell, it’s ’cause you got so old I fixed this up.”

While the space is nice for a cowboy’s bunkhouse apartment, it’s humble by almost any other standard. Boots has acquired few possessions that aren’t directly required for his trade. He doesn’t own a single short-sleeved shirt, much less a pair of shorts. The only decor in the living area is a table crowded with trophies, plaques, and commemorative firearms that Boots has been given over the years. His bedroom is even more spartan. On the dresser, he keeps a row of belts coiled with their buckles facing up. Above them, a program from Miss Anne’s 2020 funeral is stuck to the mirror. On the wood-paneled wall next to the bed hangs a single photograph of Boots with Lauri and Nelda.

This is the quiet reality of cowboying rarely depicted by Hollywood or in novels. Panhandle author and rancher John R. Erickson, famous for his Hank the Cowdog series, wrote in his 1980 nonfiction book Panhandle Cowboy, “A cowboy is one who breaks another man’s horses, feeds another man’s cattle, digs another man’s postholes, lives in another man’s house, and occupies a piece of earth that belongs to someone else.” Boots knew all this. But for him, the sometimes bitter drawbacks were well worth the rewards. He’s grateful he’s been able to lead this life for more than seventy years.

Of course, he hasn’t been able to do it alone. He has long been surrounded by others—Nelda, Miss Anne, the cowboys at the Sixes—who have made sacrifices of their own. Few cowboys are so fortunate.

Boots will turn ninety in September. There’s a lot he’s looking forward to, including serving as the grand marshal in the Abilene rodeo and traveling to Lubbock for his granddaughter’s wedding. The rehearsal dinner will be held at the National Ranching Heritage Center, inside one of the original Four Sixes barns, which Miss Anne had relocated in 1981.

But lately he and Lauri have had some hard talks about the future. Boots doesn’t like ice or air conditioning, and they both know a retirement home is pretty much out of the question. “My prayer is—and I’ve heard him tell people this—that his horse will come in without him sometime,” Lauri told me. For now, she’s grateful to the folks in Guthrie and at the Sixes for taking such good care of her father. He can eat breakfast and lunch in the ranch’s stone mansion, and “people are always bringing him homemade cookies and inviting him over when they’re going to cook out hamburgers.” The veterinarians keep an eye on him.

He and Lauri have also discussed what will happen after he’s gone. Boots tells me there’s a hill overlooking the ranch, and at the top sits the Four Sixes cemetery. “There are several cowboys in there that I’ve worked with. I wouldn’t want no big funeral. I would imagine that they’d just gather up there and maybe set out the chuck wagon and have some coffee and get it over with.”

But Nelda is buried in Vernon. There’s a space for Boots in the plot beside her, and Lauri wants her parents side by side. Yet when that day comes, she’s not so sure. It seems that Boots’s need to be in the country and Nelda’s love of town may follow them into the afterlife. “He always says that he and Mom talked about it, and that they’ll be together in heaven but they don’t have to be buried together,” Lauri told me.

Such concerns are mostly far from mind for Boots, especially when he’s out on horseback, prowling for cattle. Leaving the ranch, I thought back to the morning roundup. After the bulls were loaded, Boots dismounted and took a moment to scratch Cool’s neck. He leaned in close. No one else could hear, but he seemed to be whispering a word of thanks.

This article originally appeared in the June 2022 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Bronc-busting, Cow-punching, Death-defying Legend of Boots O’Neal.” Subscribe today.