A longer version of this essay first appeared in Art and Illustration for Science Communication © 2022 Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Art and science might be humankind’s two most noble enterprises, and they have lived culturally hand-in-hand ever since our first applications of paint to depict animals, people, and action on the walls of caves. The great mathematician-philosopher Jacob Bronowski argued that they share common origins within the human psyche, driven by two parallel and powerful inner forces: our persistent curiosity and our vivid imagination.

The symbol and the metaphor are as necessary to science as to poetry.

In Bronowski’s words, “The symbol and the metaphor are as necessary to science as to poetry” and, “the discoveries of science, the works of art, are explorations…of hidden likeness. The discoverer, or the artist, presents in them two aspects of nature and fuses them into one. This is the act of creation, in which an original thought is born, and it is the same act in original science and original art.”

As scientists, we organize and codify our explorations, building upon the organized curiosities of our forebears. As artists, we craft our “data of the senses” into expressions of curiosities and perceptions, interpreting and evoking human emotions. Both of these endeavors involve experimentation and vision, as well as mistakes and failures. Science advances by pushing the boundaries of observation, evidence, and logic while staying aware that ideas are vulnerable. Art advances along remarkably parallel tracks, relentlessly probing boundary zones between observation, interpretation, and imagination, sometimes achieving brilliance, and other times falling flat.

In 1505–06, for example, Leonardo da Vinci wrote Codex on the Flight of Birds, having studied how birds fly and imagining how humans might mimic them. His ideas about human flight were abject failures, but his copious illustrations became timeless masterpieces of imaginative engineering.

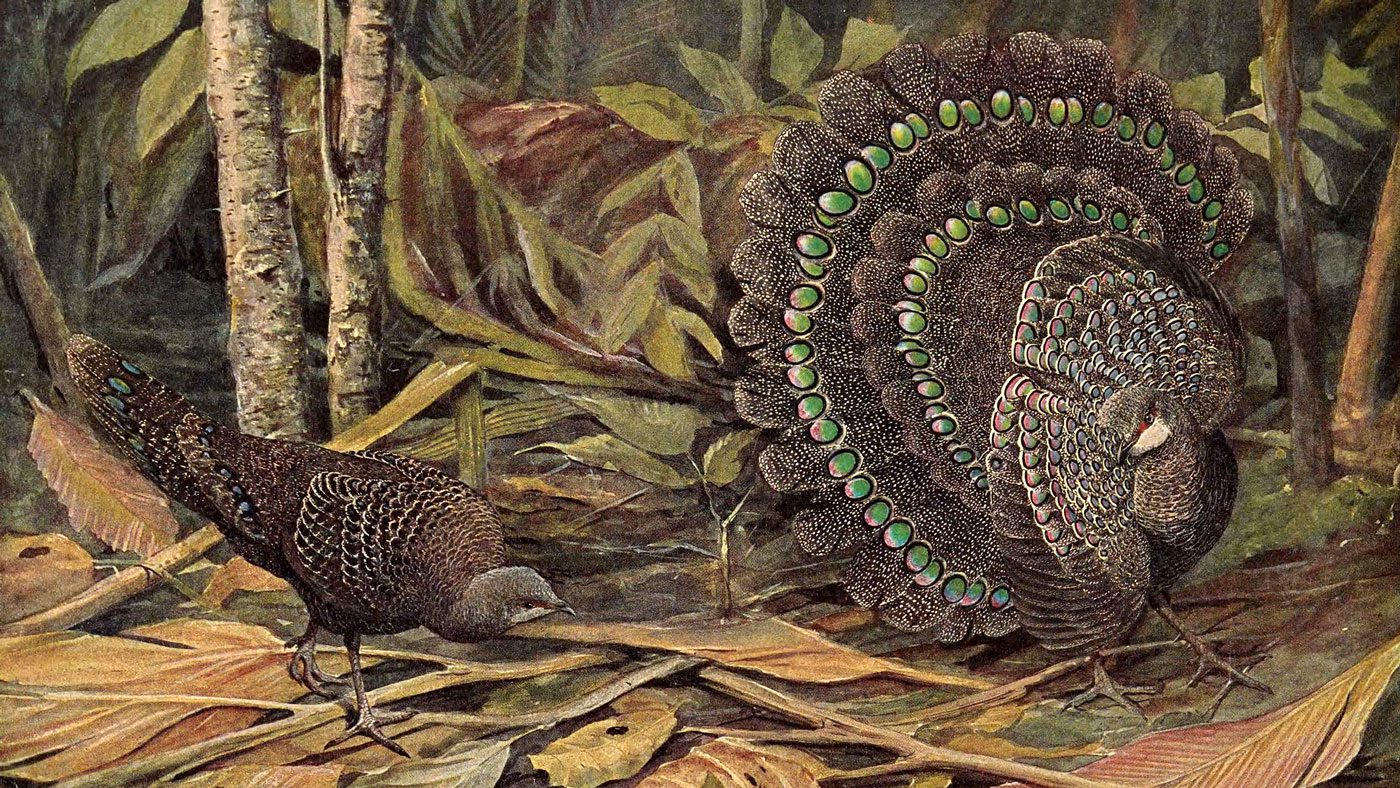

By the 18th and 19th centuries, ornithologist-explorers such as Mark Catesby, William Bartram, Alexander Wilson, and John James Audubon were making fundamental scientific contributions while also exploring previously uncharted artistic spaces. For example, it was the British Museum’s ornithologist John Gould—famous for ground-breaking lithographs largely created by his wife, Elizabeth—who first recognized multiple distinct species among finches and mockingbirds collected by Charles Darwin on the Galápagos Islands, helping pave the way for Darwin’s foundational insights into evolution by natural selection.

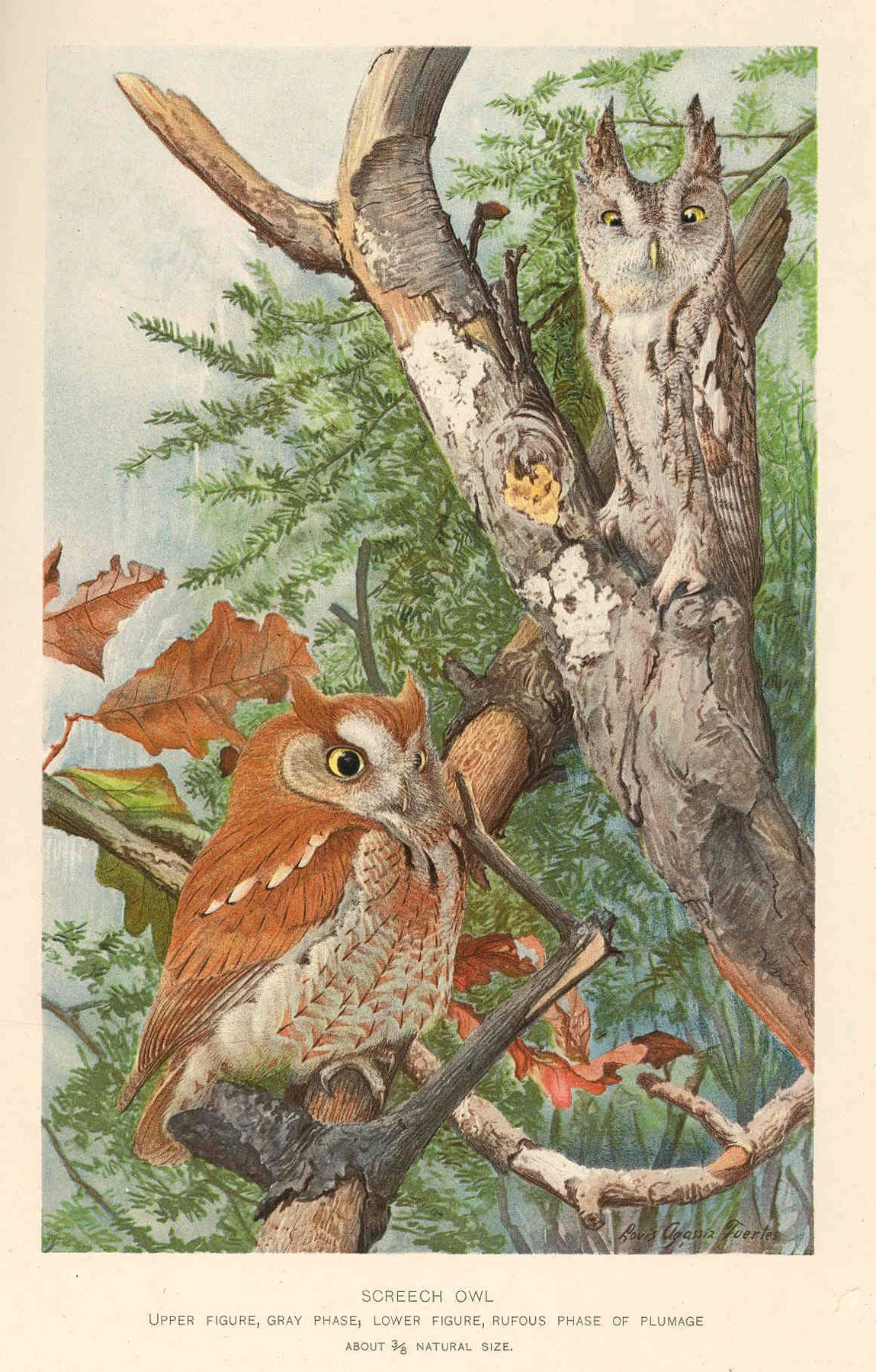

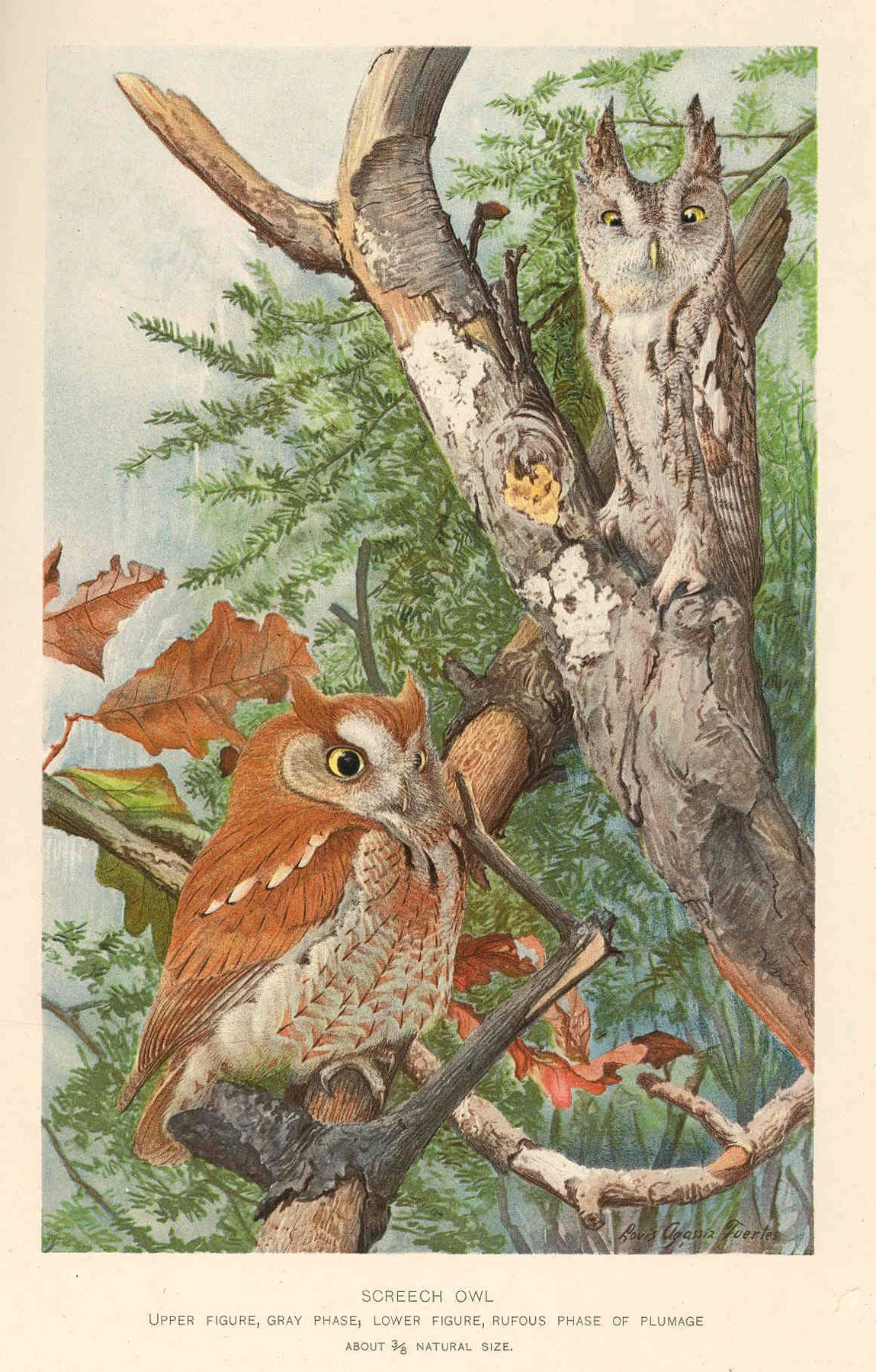

To this day the world’s great natural history museums routinely bring artists and scientists together in order to catalog and understand the natural world, and to inspire the public about its wonders. Pioneering naturalist painters of the early 20th century like Liljefors, Fuertes, Rungius, Jaques, Sutton, and Peterson graced both the walls of museums and the pages of influential books, effectively blurring the distinctions between science and art in our discipline.

Universal Accessibility and Striking Variety

The interweaving of art with science at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology owes its origins to a Cornell professor in the early 20th century. Arthur A. Allen, the founder and first director of the Cornell Lab, understood that birds possess two great powers: universal accessibility and striking variety, making them outstanding subjects for scientific breakthroughs about form, function, and ecological relationships. Equally, however, Allen appreciated how deeply birds appeal to the human imagination, thus making them focal subjects in painting, sculpture, poetry, song, and folklore through all ages and cultures.

As luck would have it, the junction of 19th and 20th centuries produced a gifted young bird artist named Louis Agassiz Fuertes, who is often referred to as “Audubon’s successor.” Fuertes lived in Ithaca, attended Cornell University, and became fast friends with Arthur Allen. This influential friendship helped reinforce Allen’s recognition of how powerfully birds stimulate the human psyche—both as subjects of science and as inspirations for art.

It is tempting to speculate that Allen, with his naturalist’s intuition, recognized that birds activate both sides of our brain. This idea gained currency much later as a popular concept in neurobiology—that the left-brain manages important features of intellect, speech, logic, and reasoning; while the right-brain handles less linear functions—the artistic, emotional, and spiritual components of our personality.

Birds commingle our intellect with our aesthetics. They capture both our minds and our hearts.

Birds possess the extraordinary power to light up both sides, often simultaneously. We study them, count them, learn nature’s secrets from them, even as we marvel at them, write songs and poetry about them, love them, and even worship them. Perhaps more than any other group of organisms, birds commingle our intellect with our aesthetics. They capture both our minds and our hearts.

As his long career at Cornell progressed, Arthur Allen increasingly focused on pioneering nature photography, natural history filming, sound recording, and studio productions for the general public. Among his dozens of students were talented artists such as Robert Mengel and George Miksch Sutton who incorporated sketches, technical illustrations, and color paintings into their publications. Allen’s launch of an annual journal called The Living Bird in 1960 was a milestone in ornithology, in large part because each issue interspersed dozens of line drawings, scratchboards, paintings, and even poetic verse among its dozens of technical papers.

Living Bird in its original form was a scientific and artistic success, but it circulated to only a few hundred scientists, supporters, and libraries. By 1981, when Charles Walcott arrived at the Lab to become its new director, birdwatching was gaining momentum as a popular outdoor pastime. Walcott made the bold move to convert Living Bird into the award-winning color quarterly magazine that it remains to this day. As the Lab’s signature magazine, Living Bird continues to pair extraordinary photography and illustration with top-flight science journalism written to stimulate, educate, and inspire a broad public audience about the wonders of birds and their places, habitats, behaviors, and vulnerabilities. In this way, every issue strives to be a quintessential melding of art and science.

art Finds a Home at the cornell Lab

Today the halls, walls, and grounds of the newly renovated Johnson Center for Birds and Biodiversity are adorned with paintings, prints, and sculptures by fine artists varying from the traditional realism of Louis Agassiz Fuertes and Frances Lee Jaques to the poignant sculptures of Todd McGrain and the witty, colorful avian graphics of Charley Harper. Two colossal murals grace our Visitors Center. James Prosek’s Wall of Silhouettes, inspired by Roger Tory Peterson’s iconic endpapers from A Field Guide to the Birds, pays homage to the role of birdwatching in the scientific study of birds and their habitats. Jane Kim’s From So Simple a Beginning is a monumental 2,500 square-foot mural presenting a stunning journey through 375 million years of evolution, beginning with the earliest marine tetrapods and ending with a vibrant celebration of modern birds and their global prevalence.

Maya Lin’s elegant Sound Ring is an interactive audio-sculptural component of her What is Missing? memorial to threatened and extinct biodiversity around the world. Todd McGrain’s evocative two meter tall Passenger Pigeon longingly faces skyward just outside the Lab’s entrance, one of five pieces in his dramatic Lost Bird Project. Hidden along a forested trail amidst Sapsucker Woods is a captivating, egg-shaped stone obelisk donated and constructed in situ by the artist Andy Goldsworthy. Closer to the building, a life sized, gleaming stainless steel Whooping Crane entitled “Invitation to the Dance,” by Kent Ullberg, was unveiled in 2018 to honor Dr. George Archibald for his research on cranes as a Cornell graduate student, and his subsequent founding of the International Crane Foundation.

the bartels science illustration program

Fine art of the highest caliber percolates through the Lab’s science and outreach, in no small part thanks to the vision of Phil and Susan Bartels. In 2003 they helped the Lab establish the Bartels Science Illustrators residency program. This unique and highly competitive annual fellowship has allowed the Lab to host a remarkable series of early-career artists who join us at our headquarters in Ithaca, usually for a year. Artists come from all corners of our country and beyond, challenging themselves and the many scientists around them to explore both sides of our brains.

Their styles and favored media are as varied as art itself, and over the years their contributions to the Lab’s scientific and public outputs have been prodigious. While learning from Lab experts and our scientific collections exactly how birds are shaped and feathered, Bartels Illustrators have given back to the Lab and the greater science communities by creating local field guides, participatory science materials, data visualizations, technical illustrations, playful cartoons, and even cover art for magazines and journals.

Many of us fell in love with birds because they stimulated our imagination and captured our hearts as well as our minds. As each Bartels Illustrator arrives at the Lab, their work reminds me that ornithology is an extraordinarily visual science. Their work reminds me of Bronowski’s profound insight that creativity and evolutionary progress in both science and art stem from the same, remarkably human union of curiosity and imagination. The very existence of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology is a celebration of this union.

About the Author

John W. Fitzpatrick served as the Executive Director of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology from 1995–2021. Read more about Fitz, including both his scientific career and his artwork, in this profile from Living Bird magazine.

About the Bartels Science Illustration Program

The Bartels Science Illustration residency supports illustrators who are just starting their careers to build their portfolios by working on projects at the Cornell Lab. Their work is published regularly in Living Bird magazine, our All About Birds website, participatory science materials, and in scientific publications.

View the work of the 30+ talented illustrators that have been part of the program since it began in 2003. For more information visit the Bartels Science Illustration Program website or contact program coordinator Jillian Ditner.