As if we need more dumbed-down histories. After panicking Texans banned “critical race theory” and books by Black, indigenous, people of color, and queer authors, Governor Greg Abbott signed the 1836 Project into law last September to create a “patriotic education” to assimilate would-be Texans. A nine-person committee chosen by the governor, lieutenant governor, and the house speaker—all Republicans—will create a pamphlet to be issued with every new driver’s license that “explains the significance of policy decisions by this state to promote liberty and freedom for businesses and families.”

Texas State Representative Tan Parker filed his 1836 Project bill last year because “the liberal agenda is not to tell the full history of this state or this nation.” He blamed attacks on his idea on journalists who “want to divide America.”

The guide promises to contain a “greatest hits” of Texas’ founding myths, including what’s become the now-standard glorification of the Alamo battle, promotion of theocratic “Christian heritage,” and possibly the falsehood that Texas joined the Confederacy in 1861 to defend states’ rights. The project came into effect without funding, but whatever the cost is, the Texas Education Agency and Department of Public Safety will pick up the tab. We won’t know what’s in the pamphlet until publication.

The committee first met in January, and between now and the deadline for their work on September 1, it will have a single day for public comment. Readers can find meeting updates on the Texas Education Agency website.

At the committee’s most recent meetings in March and April, members trumpeted liberty and freedom for all Texans and the state’s uneven economic wealth, but avoided discussing anything specific. Shalon Bond, the first Black president of the Texas Council for Social Studies, was one of five experts invited to speak at the committee’s March meeting.

“We would like to be your greatest asset for this project,” Bond said—to which former Land Commissioner Jerry Patterson asked for specific historical narratives that need revision, an encouraging signal the project may not be the total whitewash critics feared. Bond enthusiastically promised to gather ideas from TXCSS members and email a detailed list of neglected narratives. Yet two months later, Bond has not sent any recommendations to the committee. When I requested her list in May, she didn’t remember her commitment to advocating for a more inclusive 1836 Project, let alone sending marginalized histories to the committee—a discouraging lapse.

Based on some committee members’ views expressed in other venues, the end product will recapitulate our state’s same incomplete historical narrative.

Sherry Sylvester, a senior fellow at the conservative Texas Public Policy Foundation and a committee member appointed by Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, her former employer, denounced the media recently on an extremist podcast for warping the Disneyfied historical narrative she prefers.

“All of a sudden, our country is founded on racism, is riddled with racism; Texas is riddled with racism—everyone at the Alamo, according to them, fighting for slavery—which is completely wrong,” Sylvester said.

A moment later, she declared that the Black Lives Matter movement has made it a priority to destroy the nuclear family because it embraces transgender children. She explained that the goal of the 1836 Project was to educate new Texans about pro-business and conservative values.

“We want people who come in here to not California our state,” she said.

Named for the year of Texas’ independence, the 1836 Project is modeled on the Trump administration’s 1776 Project, which similarly promoted a “patriotic education” and pushed a Reaganesque view of the past. Criticized for historical inaccuracies and partisanship, President Joe Biden abandoned it the day he took office.

The 1836 Project is a rebuke to The New York Times’ 1619 Project, which seeks to reframe our national story by starting in August 1619, when the first enslaved Africans arrived in colonial Virginia, rather than 1776, and recognizes that the United States was built upon the whip-wounded backs of enslaved Blacks. Last year, Texas outlawed the 1619 Project curriculum from schools, taught in more than 5,000 classrooms nationwide.

“We want people who come in here to not California our state.”

The 1836 Project will perpetuate stubborn 19th-century myths that will not die: Texas, for instance, has always stood on the side of freedom and liberty. Hard work alone inevitably leads to success. “Business-friendly” tax breaks make for a prosperous populace without the need for a robust social safety net and social services.

In reality, thanks to its stingy government, Texas has the fourth-lowest literacy rate in the U.S., comes first in the rate of medically uninsured people nationwide, and ranks eighth on income inequality. The governor wants to stop teaching noncitizen children who attend public schools—an idea as cold-hearted as it is illogical and dumb. Forget our obesity epidemic, infrastructure failures, and militarized border.

The project is a politics of distraction. It’s designed to keep Texans from examining their true history, forget how the powerful are ripping them off, and stop them from pushing back against an extremist state government. For their children, the purpose is to further erode critical thinking skills. The long-term effect is a bifurcated electorate and an incongruent shared history. The myth of the Alamo, and by extension the Texan persona, is a ready-made and highly portable identity due to advertising and Hollywood’s John Wayne-like portraits. Yet, our state’s true history is only superficially understood by outsiders and even Texans themselves. Ask around and most adults in the state are surprised to learn the more accurate, nuanced history on which our culture stands. Texas is not the monoculture 1836 supporters want newcomers to adopt.

When the 1836 Project was only a bill, Donald Frazier, director of the Texas Center at Schreiner University in Kerrville, told The New York Times that “honest” historians must be on the committee to provide an accurate narrative of Texas history. In September, Governor Abbott appointed Frazier to the committee. Frazier told me he intends to counter misinformation like that peddled by the “dishonest journalists.” They, he said, tied Texas founders to white supremacy in the book “Forget the Alamo,” the story of the Texas founders’ revolt against Mexico to avoid taxes and keep slaves.

“Texans are suspicious of authority, and Texas is a particular expression of the American experience,” Frazier said.

This suspicion of authority apparently does not entail questioning the policies and laws that have made the state a national and internatinoal embarrassment. Unbridled gun ownership aside, Texans are not widely known to aggressively protest government intrusion into the lives of anyone except white Christians and property-owners. There was no defense of transgender children and their parents when Attorney General Ken Paxton deemed gender-affirming healthcare for trans kids as child abuse; Governor Abbott ordered social-service agencies to investigate their parents. Many Texans cheered when Abbott signed into law a new ban on 24-hour and drive-through voting, which targeted the working poor, who have limited time and means to participate in democracy before and after their work shifts—a class that is disproportionately people of color. Why any Texan suspicious of authority supports voting restrictions is beyond comprehension.

“No free person of African descent, either in whole or part, shall be permitted to reside permanently in the Republic.”

Kevin Roberts, a supporter of Trump and president of the right-wing advocacy group The Heritage Foundation, is chair of the 1836 Project. At the 1836 committee’s first meeting in January, Roberts cast doubt that the committee would be a neutral, honest, all-inclusive advocate for telling the state’s history:

“The United States,” he said, “Especially Texas, are places where we can live the dream of prosperity and liberty and flourishing better than anywhere else on earth.”

According to the Legatum Institute, a London-based conservative think tank, Texas ranked thirty-third of the fifty states on its 2021 United States Prosperity Index. The academics and researchers who constructed the index found Texas ranked 39 in personal freedom, 40 in living conditions, 42 in education, and 35 in health. The study ranked Texas 43 for “inclusive societies”—the index’s measure of “prosperity, where social and legal institutions protect the fundamental freedoms of individuals and their ability to flourish.” The Legatum Institute placed the United States 20th overall, behind the socialistic European countries, and 69th and 68th among 167 countries for security and health, respectively. The Center for Women and Politics ranked Texas last in the U.S. for the abysmal number of women elected to local offices here.

Roberts is not the only member who appeals to nostalgia. Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, a believer in the racist Great Replacement Theory—which claims political elites encourage illegal immigration in the hopes of gaining their votes, therefore replacing the white majority—appointed sentimental state Senator Brandon Creighton to the committee. Creighton proudly reminded his colleagues that Martin Parmer, a signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence and the chairman of the 1836 Constitutional Convention, was his five-time great-grandfather.

True to 1836 Project form, the senator skipped Parmer’s support for slavery. Parmer and 55 other insurrectionists signed the 1836 Constitution, which enshrined slavery as the economic engine of the economy shortly after the Alamo battle before the Texans defeated Santa Anna at San Jacinto and exchanged Santa Anna’s life for the territory. The founders prohibited the new legislature from emancipating enslaved people or allowing them to be exported farther east.

“No free person of African descent, either in whole or part, shall be permitted to reside permanently in the Republic,” the document read.

To curry favor from potential cotton markets in Europe, especially Great Britain, which abolished the transatlantic slave trade, Texans declared that importing humans from lands other than the U.S. was “forever prohibited, and declared to be piracy.” Nevertheless, the new Republic provided the most protections for its slaveholders in North America.

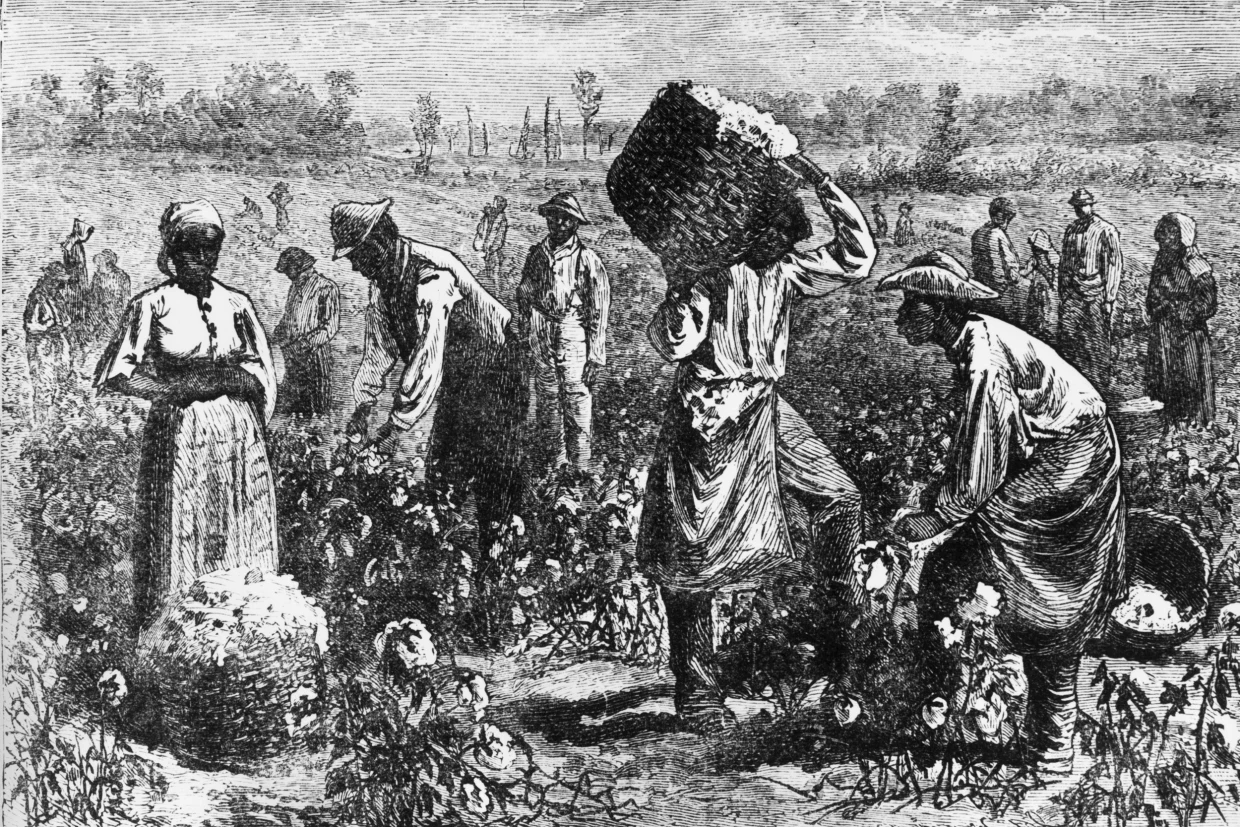

Too often, Texans like Creighton fetishize the Battle of the Alamo as a struggle between an oppressive Mexican dictator and righteous Anglo colonists and Trojans. As the sterile Alamo website summarizes, “freedoms worth fighting for.” Yet the three most famous rebel heroes—the saintly James Bowie, Williams Travis, and David Crockett—fought to preserve one “freedom” above all: the right to buy and keep slaves, which Mexico outlawed some years before. And if they and their Anglo compatriots could not legally bind Blacks to their plantations, the rebels would take Texas through violence. The Republic’s origin story, as it is popularly told now, negates the tens of thousands of Black, Indigenous, and Mexican lives exploited, abused, and snuffed out to enrich and build the state.

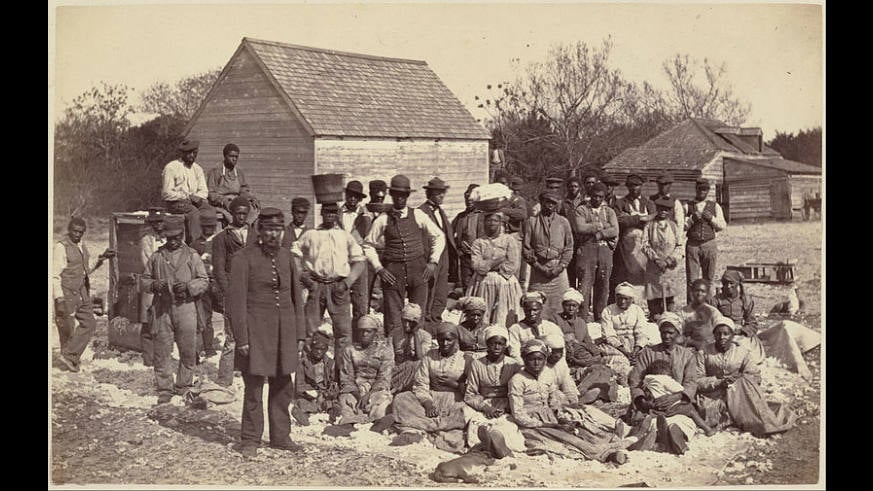

There is no debate: Texas was built on cotton and slavery. In the 1820s, Stephen F. Austin introduced American-style slavery to Texas in exchange for land and encouraged the importation of enslaved people to grow the nascent economy. According to Andrew J. Toget’s “Seeds of Empire,” the number of enslaved people and slaveholders tripled in the first three years of the Republic as the Cotton Empire expanded westward from the South. After 1836, as white migration increased, former Tejano allies were discarded, discriminated against, and disenfranchised from political leadership and property in the new nation after supporting the Anglo insurrection, most notably Juan Seguín.

After he fought to defeat Santa Anna and became the first Tejano state senator, Anglos accused Seguín of treason and chased him and his family out of the country. Historian Raúl Ramos discovered an 1837 pamphlet printed in Puebla that revealed how Mexicans viewed the Anglo rebels in northern Mexico: “inherently prone to enslaving people of other races and stealing land.”

Suppose the 1836 Project is to approach anything close to faithful and honest Texas history. In that case, the committee needs to invite professors like Ramos and Torget, a historian at the University of North Texas, to their meetings and incorporate their research into the final product.

An 1837 pamphlet printed in Puebla revealed how Mexicans viewed Anglo rebels in northern Mexico: “inherently prone to enslaving people of other races and stealing land.”

When the U.S. invaded Mexico and annexed Texas in 1846, a generation raised on warped slaveholder logic—the God-given superiority of the pale race over everyone else—was embedded in Texas culture. In its 1861 Constitution, as the state joined the Confederacy, Texans explicitly opposed the Founders’ ideal of equality.

“The situation in Texas was peculiar,” wrote W.E.B. DuBois in 1935. “During the [Civil] war, Texan produce had been seat to Europe by way of Mexico, and a steady stream of cash came in, which made slavery all the more valuable. At the end of the war, slavery was essentially unimpaired. Some of the planters set their Negros free when the Federal soldiers approached, and some Negros ran away. Still, most of the Negros were kept on the plantations to await Federal action, and there was widespread belief that slavery was an institution and would continue in some form.”

It wasn’t until 1870, five years after the Civil War, that Texas ratified the 13th Amendment to the Constitution and the formal end of chattel slavery—with one exception: prisoners.

Today, Texas is one of only five states that still exploits the Amendment’s prisoner loophole. Texas Correctional Industries, a for-profit department in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, hauled in more than $48 million last year with the help of slave labor. Inmates manufacture office furniture, high school gym lockers, bleachers, Lone Star-embroidered totes, garments, and shaving bags, among other items, for no pay.

A joint resolution proposing a state constitutional amendment to end all forms of forced labor was introduced in 2021 but has yet to get through the Texas legislature. It never made sense to keep the door cracked open for slavery, even less now that Texans know there is something we can do to end such cruelty. Civil rights and equality continue to lag the state’s boosterism. The Texas prison population is about 33 percent Black—nearly three times higher than the Black free population. The disproportionate minority inmate population is an injustice linked to the legacy of the 1836 Constitution and every anti-Black law and anti-democratic voting law passed since the Emancipation Proclamation.