Last year, the North Dakota House of Representatives overwhelmingly passed a bill that threatened tenure protections. It would have allowed the presidents of Dickinson State University and Bismarck State College to fire tenured faculty members without any review from a faculty committee.

The bill had high-ranking backers. Steve Easton, Dickinson State’s president, drafted a version of the measure for the leader of the House Republican supermajority, calling it the “Tenure with Responsibilities Bill.” Faculty members were alarmed and spoke out against it. Just after the House passed the measure, the State Board of Higher Education, which employs Easton and the other public college and university presidents, finally took a public stand against it.

Mark Hagerott, chancellor of the North Dakota University System, carried the message to state senators, telling them in written testimony that “The board feels strongly that the award of academic tenure” should stay under the board’s “constitutional authority.” The state Senate, which had only four Democrats (all in opposition) out of 47 members, ended up rejecting the bill by just two votes.

But that wasn’t all Hagerott had told senators. He also wrote in his testimony that the board, whose members are appointed by Republican governor Doug Burgum, was “willing to work with ND legislators to conduct a joint study to examine the post-tenure review process.” Now, roughly a year after the bill’s failure, a draft report from a board committee suggests the board may push for far broader reductions to tenure protections than the legislation would have implemented. The changes could affect 11 public higher education institutions, with a stated goal of fewer tenured positions specifically at the state’s community colleges.

“We are going to be, unless the board surprises me, reducing the number of tenured professors at the community colleges,” Hagerott told a legislative committee earlier this month. He connected this to another hot higher education topic, artificial intelligence, by saying he’s heard human lifespans will increase.

“So if you have 96 percent of your benefitted faculty at one of our community colleges have tenure and their longevity keeps going up, how do you get new blood in here, how do you get the new professors?” Hagerott said. “So we’re taking this on. It’s been quite tense, but we believe it’s the intent of the legislature [that] we look at this, and we’re working on that.”

The continued North Dakota tenure debate comes after multiple bills that would have diminished tenure protections were introduced, but failed, in multiple Republican-controlled state legislatures in 2023. But Indiana’s legislature passed one this year. Further, in response to political pressure, several state governing boards appear to be carrying out some of the GOP lawmakers’ wishes. (North Dakota only has regular legislative sessions in odd-numbered years, and leading lawmakers declined to say what they may be planning for tenure on their own in 2025.)

If tenured positions, or the protections that tenure affords, are ultimately reduced in North Dakota—by the board, the legislature or both—it will be part of a longtime rise in the share of non–tenure-track faculty members within higher education nationally. The American Association of University Professors says 68 percent of U.S. faculty members held what it calls contingent appointments in fall 2021, compared to about 47 percent in 1987.

A Goal to Drop Tenure Rates

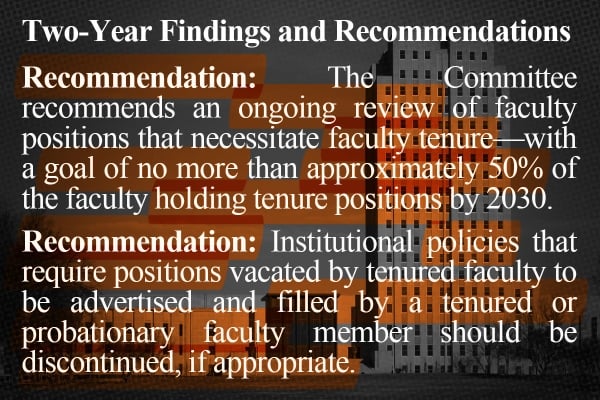

The draft report from the board’s Tenure/Post-Tenure Ad Hoc Committee makes some sweeping recommendations that could lead to double-digit decreases in the share of tenured and tenure-track faculty members at community colleges, along with reductions in the award of tenure on all state campuses.

For the two-year colleges, it suggests “a goal of no more than approximately 50 percent of the faculty holding tenure positions by 2030.” That would be a big change: Currently, only one public institution in the state has no more than 50 percent of its faculty in tenure or tenure-track positions, the report says. At one two-year college, the North Dakota State College of Science, the rate is 97 percent.

The report includes comparative information from other Upper Midwest states showing most of their community colleges don’t have high rates of tenure. “Little or no tenure was awarded to faculty at two-year institutions in Iowa, Montana, Nebraska, South Dakota or Wisconsin,” the draft says. “Conversely, Minnesota two-year colleges had the highest percentage of tenured faculty with nearly 100 percent either tenured or on a tenure track.”

Last month, a different North Dakota board committee temporarily held up tenure approval for a dozen more community college faculty members, according to Lisa Johnson, the university system’s vice chancellor for academic and student affairs. The full board ultimately approved them within a week.

At least one board member has been openly questioning the value of tenure, at least for nonresearchers in community colleges. The North Dakota Monitor quoted Kevin Black, an oil and gas industry executive, asking in a recent meeting, “How does tenure provide academic freedom in a technical education role?” and saying “this board needs to really think hard about the application and the validity of tenure in a purely instructional setting.” He was also quoted as saying, “I have not found anywhere that there’s discussion about tenure as a general concept.”

Black told Inside Higher Ed in an email that “I don’t have anything else to add other than what I’ve stated publicly, which represents my current thoughts on the matter. I’m closely watching the ad hoc committee and will provide my thoughts on that work and additional steps I would like to see.”

Academic affairs officials at four of the state’s five community colleges—Lake Region State, Williston State, Dakota College at Bottineau and North Dakota State College of Science—have, unlike Easton, the Dickinson State president, defended tenure at their institutions. “Faculty hired with the special appointment [non–tenure track] contract have almost zero job security from year to year as their contract is renewed only at the discretion of the institution’s president,” they wrote to the board.

Tenure, they wrote, is an important safeguard of academic freedom in teaching, not just research. “We believe in the importance of policy that guarantees academic freedom in teaching and research, provides for the faculty member’s security of position and recognizes their important contribution to shared governance,” they wrote.

At both community colleges and four-year regional institutions, the draft recommends that any policies requiring “positions vacated by tenured faculty” to be refilled with tenured or tenure-track faculty members “should be discontinued, if appropriate.”

The draft report also appears to advocate earlier intervention by presidents and provosts in deciding who should get tenure. Traditionally in the U.S., faculty members recommend who should and shouldn’t get tenure, and provosts, presidents and boards generally honor those recommendations at the end of the tenure review process. But the draft report recommends that “involvement of the campus president or provost in the review of probationary faculty must occur earlier in the process.”

The draft report also generally calls for more “rigorous” post-tenure review processes for faculty members. Some institutions’ presidents said they don’t even have a post-tenure review process currently. The draft says that “individual faculty productivity should be factored into” both pre-tenure and post-tenure review.

Timothy Mihalick, chair of the State Board of Higher Education and a member of the committee that produced the draft report, told Inside Higher Ed that he didn’t want to go into detail about the future of tenure in North Dakota until the report is finalized. Mihalick said there needs to be more discussion at the full board level, which could go in a different direction than what’s floated in the draft. “There’s nothing in concrete form,” he said.

It’s also unclear to what extent the board would go beyond recommendations and force the public institutions it oversees to follow suit. Johnson, the system vice chancellor for academic and student affairs, said she doesn’t know where the board will land, but that it does have the power to carry out the recommendations.

Derek VanderMolen, outgoing president of the North Dakota Council of College Faculties, said he’s “heard no dissent against the topic of post-tenure review and the need for post-tenure review.” But VanderMolen said he’s heard faculty concerns from across the state about the goal of having no more than half of community college faculty members in tenured positions.

“There has been nothing provided saying here’s where the [50 percent] number comes from, or any reference or any best practices method or any idea where that came from or any research indicating why that’s a good number,” VanderMolen said. “It’s just the number that was given.”

North Dakota United, a union that includes higher education employees among its members, is asking people to write to the board members and Hagerott about how tenure protects academic freedom. It said the draft report’s recommendations “reduce the job security of all tenured faculty and arbitrarily limit the number of tenured positions at two-year colleges.”

Nick Archuleta, the union’s president, said last year’s failed bill “was sort of the genesis of this anti-tenure business.” He said that “it started because basically Dr. Easton was having trouble communicating with his staff” and seemed to think that tenured professors were an obstacle to his plans. The tenure discussion has now outlived the bill. “Frankly I don’t understand the reason for picking this fight right now,” Archuleta said. “I just don’t.”

In a brief interview with Inside Higher Ed, Hagerott, the system chancellor, defended Easton and said he was surprised Archuleta would “disparage a president” and “not just stick to the facts that technology is rapidly changing, our economy is changing up here, and we have to have the ability to adapt.”

Hagerott said Dickinson State is now considered a community college, tech/trade school and a liberal arts institution, and “to do that you’ve gotta have the ability to reprogram money and build new programs.” But, he said, there’s “a system of tenure that [creates] high-longevity positions, and yet we’re in a period of rapid change.”

A Tenure Critic Initiates His Own Reforms

Easton told Inside Higher Ed that he stopped advocating for the 2023 bill publicly when the board took a position against it. But he said he still provides his views on tenure when he’s asked about it, and that inquiries have come from board members. “I’m not the initiator of phone calls,” he said.

Easton had plenty to say, however, when the board asked for his and other presidents’ input on tenure as part of an official survey. Easton wrote that the board should consider a policy making it a “default presumption” that “faculty members are not hired or placed onto a tenure track at regional universities and state colleges.” He wrote that the board should have to approve any new tenure-track position at these institutions, and only for situations in which the faculty members will serve in leadership roles or will perform “substantial research.”

He wrote that his own institution needs “to put teeth into the post-tenure review process, by putting responsibility for that process in the hands of administrators, instead of those who see their jobs primarily as fellow teachers.” The board should also consider new criteria for post-tenure reviews, he wrote, including how well faculty members recruit and retain students and how much tuition revenue they generate “compared to the faculty member’s total compensation.”

Easton is already implementing a similar calculation at Dickinson State, putting new criteria into contracts for faculty members next academic year, including tenured professors. Contracts now generally include a requirement to “produce” credit hours—one provided to Inside Higher Ed said “produce at least 320 modified credit hours in the academic year in classes with at least nine students per class,” or six students for graduate-level classes.

Failure to meet this can result in contract nonrenewal, even for tenured faculty members, or pay cuts, the contract said. Easton has laid off tenured faculty members before, citing low class enrollments.

The credit-hour production requirements are part of an effort “to keep our student costs as low as we reasonably can,” Easton said. He said that “if we have large numbers of small enrollment classes,” students and North Dakota taxpayers pay for that “inefficiency.”

Easton said that as demand for degrees and public support of higher education are both declining, higher education needs to become more efficient. Tenure, Easton said, “can lock us into employment relationships and an emphasis on disciplines that are no longer drawing substantial interest from students, and therefore it can make it very difficult for us to innovate in ways that make us responsive to students.”