[ad_1]

When early settlers crossed the Appalachian Mountains, they left behind the Atlantic Ocean watershed for a land where every river flowed west and south to the Gulf of Mexico.

This geographic fact stunted the economy of early Tennessee, but it wouldn’t stunt it for long. You see, in 1807 Robert Fulton drove his new steamboat upstream on New York’s Hudson River. Within a few years of that event, steamboats were making their way along the Mississippi, Cumberland and Tennessee rivers. But it took a lot longer for some parts of Tennessee to see the steamboat.

This isn’t one story — but three:

Memphis (1811)

The first steamboat to ever descend the Mississippi River almost certainly stopped at the site of present-day Memphis, but we can’t be sure. In late December 1811, the steamboat New Orleans probably stopped at the Chickasaw Bluffs of the Mississippi River, as Memphis was called then, on its maiden voyage from Pittsburgh to New Orleans.

The New Orleans was a 150-foot-long boat financed by Robert Fulton and Robert Livingston; its eight-member crew was led by Capt. Nicholas Roosevelt (a great-uncle of President Theodore Roosevelt). In the weeks preceding its stop at the Chickasaw Bluffs, the New Orleans encountered and overcame the treacherous Falls of the Ohio River, hostile Native Americans and (worst of all) the New Madrid Earthquakes.

Assuming the New Orleans stopped at the Chickasaw Bluffs, the boat didn’t stay long because the crew was trying to get to Natchez, Mississippi, as quickly as it could.

The Chickasaw Indians would relinquish their claims on West Tennessee in 1818, and it was about that time that three men (one of whom was Andrew Jackson) organized the town of Memphis, which would quickly become a stop for steamboats on the Mississippi River. As farmers in West Tennessee, northern Mississippi and Arkansas adopted cotton as their main crop, Memphis emerged as the cotton trading capital of the inland United States — and it did so thanks to steamboats.

Nashville (1818)

There used to be a long stretch of shallow water on the Cumberland River about 25 miles downstream from Nashville called the Harpeth Shoals. Because of this, it wasn’t easy to get a steamboat to Nashville.

Every Tennessee history book and article I’ve ever seen claims that the General Jackson was the first steamboat to make it up the Cumberland River to Nashville. The most detailed is “Steamboatin’ on the Cumberland” by Byrd Douglas, which claims the General Jackson was the first, arriving on March 11, 1819.

It’s very possible, though, that Douglas may have the name of the boat and the date wrong.

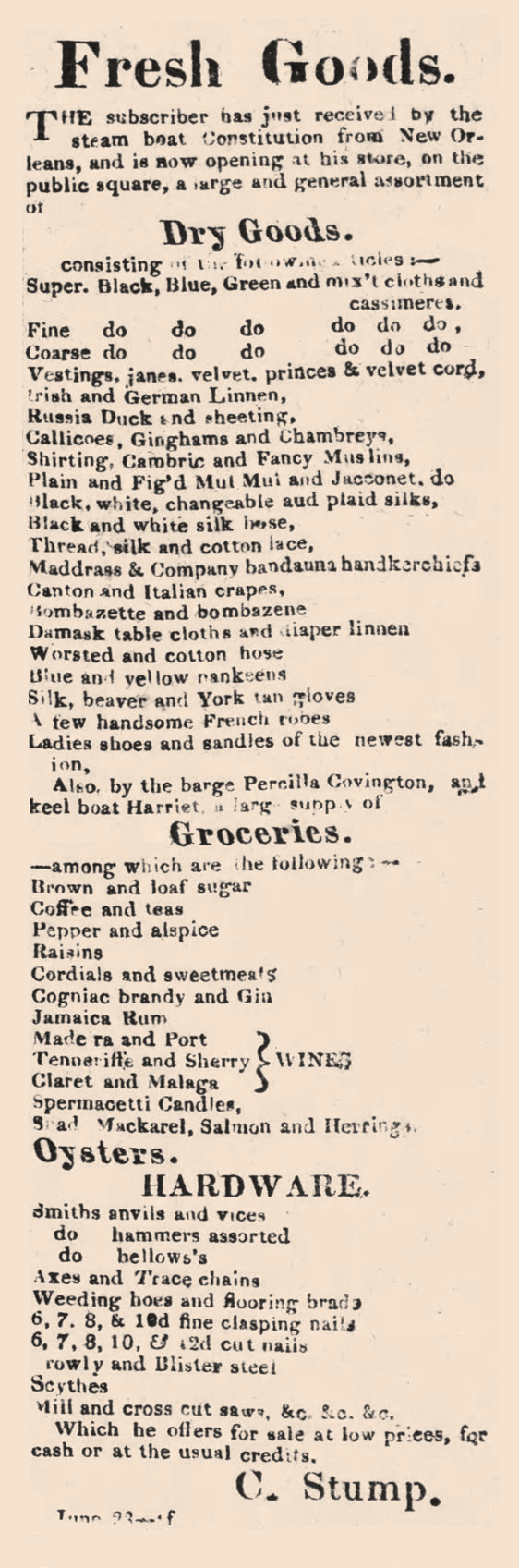

There was a prominent Nashville merchant named Christopher Stump, and he published a large advertisement that first appeared in the June 23, 1818, issue of the (Nashville) Clarion and Tennessee Gazette newspaper. In the ad, Stump claimed he had a lot of groceries, fabric and hardware to sell that he had “just received from the steam boat Constitution.”

I’ve further learned that there was, in fact, a steamboat called the Constitution built in Pittsburgh and launched in 1816. It was originally called the Oliver Evans (named for the inventor of the high-pressure steam engine) but was renamed after a deadly explosion in 1817.

I believe the reason the General Jackson was more talked about in Nashville is that it was locally owned (by former Gov. William Carroll, among others). That would account for why its arrival in March 1819 was more of a civic event than the Constitution’s arrival the year before.

Regardless of whether the Constitution or General Jackson was first, Nashville’s economy quickly adapted to the steamboat. The Harpeth Shoals remained a problem; from July to October, the Cumberland was so shallow on the shoals that boats would often get stuck there. When that happened, boats had to unload their goods below the shoals and ship by wagon to Nashville.

The Harpeth Shoals would remain an impediment on the Cumberland River until a dam created by the Army Corps of Engineers flooded it permanently in 1904.

Chattanooga and Knoxville (1828)

Steamboats did not reach Chattanooga and Knoxville until 17 years after they came to Memphis and a decade after Nashville. This is because of the many navigational obstacles on the Tennessee River such as the Muscle Shoals in northwest Alabama and the series of unpredictable features in the river in southeast Tennessee with names such as “the Suck” and “Boiling Pot.”

Steamboats were expensive, and their prominent financiers were unwilling to risk their boats on the Muscle Shoals and the Suck. Therefore, authorities in Knoxville offered to pay $640 to the first steamboat that made it to that city.

The Atlas wasn’t the first steamboat to try, but it was the first to succeed. Around Jan. 20, 1828, the Atlas made it through the Muscle Shoals with less trouble than had been expected. “We understand that is intended to take out her engine and work the empty boat over the rapids,” the Knoxville Enquirer first said. A few days later, the same paper reported that the boat made it through the Muscle Shoals without having to take that step. A few weeks later, the Atlas made it through the Boiling Pot and the Suck to the present-day site of Chattanooga (a Cherokee trading post called Ross’s Landing at the time.)

A lot of people turned out in Knoxville to greet the steamboat when it arrived on March 4.

By that late date, some of Knoxville’s business leaders realized that the steamboats would have a limited effect on that city’s commerce. After all, 1828 was the year the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad started building its rail line that would eventually connect the Atlantic Ocean to the Ohio River.

Because river access was impeded by the Muscle Shoals and the Suck, Knoxville would never really become a big steamboat town. But it would eventually be a big railroad town, and that’s another column.

[ad_2]

Source link