MK Siddiqui

MK SiddiquiThe father of an Indian teenager, who is among a handful of people to survive a rare brain-eating amoeba, has credited a public awareness campaign on social media for his son’s recovery.

Afnan Jasim, 14, is thought to have become infected in June after he went for a swim in a local pond in the southern state of Kerala.

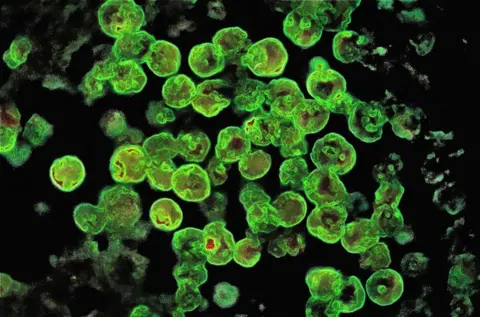

His doctor said that the amoeba – called Naegleria fowleri – likely entered his body from the water that had been contaminated by it.

Primary Amoebic Meningoencephalitis (PAM), the disease caused by the amoeba, has a mortality rate of 97%.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, between 1971 and 2023, just eight other people have survived the disease across four countries – Australia, US, Mexico and Pakistan.

In all the cases, the infection was diagnosed between nine hours and five days after the symptoms appeared – which played a crucial role in their recovery.

Medical experts say that timely treatment is key to curing the disease. Symptoms of PAM include headache, fever, nausea, vomiting, disorientation, a stiff neck, a loss of balance, seizures and/or hallucinations.

Afnan began experiencing the symptoms five days after he had gone for a swim in a local pond in Kozhikode district. He developed seizures and began complaining of severe headaches.

His parents took him to the doctor, but Afnan did not improve.

Luckily, his father MK Siddiqui, 46, had the presence of mind to connect his son’s symptoms with something he had read on social media.

Mr Siddiqui, who is a dairy farmer, said he was reading about the effects of the Nipah virus – a boy recently died of it in Kerala – on social media when he chanced upon information about the deadly brain-eating amoeba.

“I read something about seizures being caused by an infection. As soon as Afnan developed seizures, I rushed him to the local hospital,” Mr Siddiqui said.

When the seizures didn’t stop, he took his son to another hospital, but this one didn’t have a neurologist.

Finally, they went to the Baby Memorial Hospital in Kozhikode, where the boy was treated by Dr Abdul Rauf, a consultant paediatric intensivist.

“The disease was diagnosed within 24 hours of the onset of symptoms,” Dr Rauf told the BBC.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDr Rauf credits Mr Siddiqui with informing doctors about Afnan’s swim in the local pond and his subsequent symptoms, which helped them diagnose the disease in time.

The amoeba is known to enter the human body through nasal passages and it travels through the cribriform plate – which is located at the base of the skull and transmits olfactory nerves to enable the sense of smell – to reach the brain.

“The parasite then releases different chemicals and destroys the brain,” says Dr Rauf.

Most patients die because of intracranial pressure [exercised by fluids inside the skull and on the brain tissue].

He added that the amoeba was found in freshwater lakes, particularly in water that was warm.

“People should not jump or dive into water. That is a sure way for the amoeba to enter the body. If the water is contaminated, the amoeba enters through your nose,” he says.

The best thing to do, he says, is to avoid contaminated water bodies. Even in swimming pools, people are advised to keep their mouths above the water level.

“Chlorination of water resources is very important,” Dr Rauf adds.

A research paper published in Karnataka state has also reported cases of infants locally and in places like Nigeria contracting the infection from bathwater.

Since 1965, some 400 cases of PAM have been reported around the world, while India has had less than 30 cases so far.

“Kerala reported a PAM case in 2018 and 2020,” the doctor said.

Just this year, six cases have been recorded in Kerala. Of these, three have died and one is in a critical condition. While Afnan has been discharged, the sixth person has also responded to treatment and is recovering.

Baby Memorial hospital

Baby Memorial hospitalDr Rauf says before Afnan was brought to the hospital, three people had already died in Kerala from the disease.

“After two deaths at our hospital, we informed the government as it was a public health issue and an awareness campaign was launched,” Dr Rauf said. It was this awareness campaign that Mr Siddiqui had come across on social media.

Doctors conducted tests on Afnan which helped detect the presence of the amoeba in the boy’s cerebrospinal fluid – which is found in the brain and spinal cord – and then administered a combination of antimicrobial drugs by injecting them into his spine.

The treatment also included administering Miltefosine – a drug that the state government imported from Germany.

“This drug is used for rare diseases in India but it is not very costly,” Dr Rauf said.

“On the first day, the patient was not very conscious due to the seizures. But within three days, Afnan’s condition started improving,” he added.

A week later, doctors repeated the tests and found the amoeba was no longer present in his body. But he will continue taking medicines for a month, after which he plans to resume his studies.

The experience has left a profound impact on Afnan, who says he now wants to do a degree in nursing.

“He told the doctor that nurses work so hard for the patients,” Mr Siddiqui says.