In his brief statement to the House of Commons on the UK’s cost of living crisis, Rishi Sunak managed to alleviate two economic problems, but at the cost of aggravating a third.

The good news is that his actions are likely to lower the peak rate of inflation this year and will help UK households deal with immediate cost of living problems. But they will also deliver the hottest of inflationary potatoes straight into the lap of the Bank of England.

The chancellor also left hanging huge questions over what will happen to support for households next year.

The first effect of the measures is likely to be mechanical, reducing the expected increase in inflation, and potentially avoiding the dreaded rise above 10 per cent this autumn.

If household energy bills rise to roughly £2,400 a year on average rather than the £2,800 level Ofgem this week said was likely, inflation is not likely to rise as high as previously expected.

This is not certain because the Office for National Statistics has not announced whether it will classify the support as a rebate, which would limit the rise in inflation, or as support for income, which would have no impact on the measured inflation rate.

Although this difference is mostly semantic — since a rebate and income support both make households better off to the same extent — most economists think the ONS will rule that the package will lower the rate of inflation.

Ben Nabarro, chief UK economist at Citi, said he expected the £400 rebate to reduce the peak inflation rate in October by 1.3 percentage points from where it would otherwise be.

He said this would mean that “consumer price inflation would peak at an annual rate of 9.5 per cent” and retail price inflation at 11.5 per cent. This would lower the cost of servicing the government’s £500bn of debt, which is linked to RPI.

But while households will be helped by the universal support, alongside more targeted assistance for those on means-tested benefits, pensioners and the disabled this financial year, economists noted that on average households would still be worse off.

Paul Dales, chief UK economist at Capital Economics, estimated that average real household disposable income would now drop by 1 per cent in 2022, although this is an improvement on the 2 per cent drop expected before the chancellor delivered his statement.

The big question is whether the package will increase consumer spending and encourage companies to raise prices, which would fuel inflation next year, leaving households ultimately no better off at all.

An aide to the chancellor accepted that the stimulus offered by the package might be seen as inflationary, but said the net support was not that large.

Instead, Sunak passed the difficult job of controlling the level of inflation to the central bank. “I know the governor and his team will take decisive action to get inflation back on target and ensure inflation expectations remain firmly anchored,” he said.

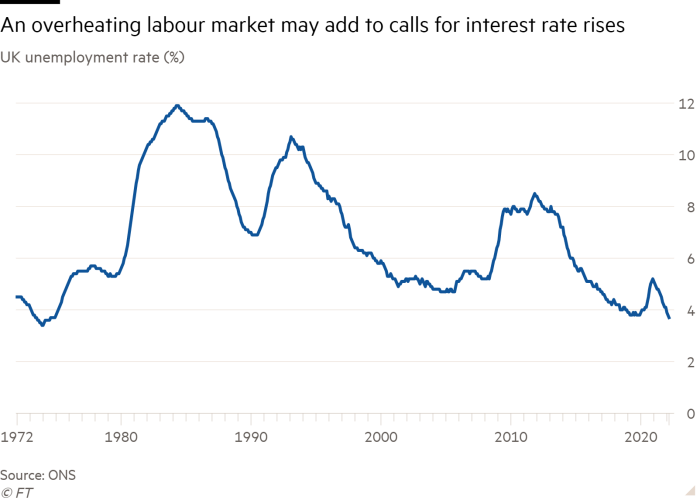

Economists agreed that Sunak’s actions would act as a stimulus, making it more likely that the BoE would raise interest rates faster and further than previously expected, but they disagreed on the extent of the monetary tightening needed to offset this fiscal boost.

Kallum Pickering, senior economist at Berenberg Bank, described the chancellor’s package as “misguided” because it “will add to demand at a time when private wages are surging . . . and most households have excess savings accumulated during lockdowns”.

“Keep this up and, eventually, the BoE will be forced to bring inflation under control by raising rates well above neutral and triggering a recession,” he added.

But Robert Wood, chief UK economist at the Bank of America, said the package would require the BoE only to impose “modestly higher interest rates” because tax revenues were also rising unexpectedly quickly.

Nabarro, who also thought the package would put only marginal pressure on the central bank to raise inflation, said hints of further tax cuts in the autumn Budget were more worrying in terms of the likely impact on interest rates.

“The question now is whether the Chancellor comes back for more before the end of the fiscal year. This seems increasingly plausible”, he said.

Economists also disagreed on the exact level of stimulus that Sunak had delivered. He told the House of Commons that the package would cost £15bn, offset by a £5bn windfall tax on North Sea profits.

But some economists said the chancellor underestimated the total stimulus in his package because he failed to count the scrapping of his February plan to claw back £40 a year over five years from a £200 loan to help households pay their energy bills.

Sandra Horsfield, economist at Investec, said: “The true fiscal support now relative to what was put on the table in February [is] some £5bn higher [than £15bn].”

The chancellor could plausibly claim that in future the windfall tax will continue to raise roughly £5bn a year until its sunset clause is activated at the end of 2025. He said that would happen only if energy prices remained high, although he failed to specify the price threshold at which the tax would be phased out.

The chancellor himself noted that the problem of inflation was becoming more broad-based, with price rises exceeding 3 per cent in four out of five categories of goods and services. As a result, economists and financial markets now expect interest rates to be significantly higher.

Allan Monks, chief UK economist at JPMorgan, said the package would help “steer the economy away from recession,” in the short term, but would come at a price of interest rates higher than the current 1 per cent rate.

“That would imply the BoE keeps on hiking at every meeting until November, taking rates up to 2 per cent by year end and then up to 2.75 per cent by next August,” he said.