You can be forgiven if you’ve never heard of the most powerful unelected man in Texas politics. Steve McCraw, the longtime director of the Texas Department of Public Safety, is not exactly a household name. And even his legions of fans and critics at the Capitol routinely botch his name, calling him Steve McGraw. Yet McCraw, who abruptly announced last week that he would retire by the end of the year, has changed Texas government and politics far more than most of the elected officials he theoretically answers to. He is the J. Edgar Hoover of Texas—a lawman-politician whose power grew alongside his longevity and usefulness to the Republican Party. And like Hoover, he seems preternaturally gifted at escaping accountability. Over time, he became too big to fail.

In 2004, Governor Rick Perry plucked McCraw from the FBI to serve as state homeland security director. In that role, McCraw alarmed civil libertarians and some lawmakers by overseeing the construction of the Texas Data Exchange (TDEx), a massive intelligence database controlled by the governor’s office. McCraw also helped Perry launch the state’s giant experiment of taking on the heretofore federal responsibility of policing the border.

Perry appointed him to lead DPS in 2009. McCraw brought with him his post-9/11-era focus on intelligence gathering and obsession with “spillover violence” from Mexico. Law enforcement traditionalists watched McCraw’s transformation of DPS with some alarm. Would the agency still be able to effectively perform its core crime-fighting functions—highway enforcement and major state criminal investigations—if its leader was more attuned to Al Qaeda and Los Zetas?

When McCraw took the lead at the agency, he inherited one of the most high-profile criminal cases in modern Texas history—the Governor’s Mansion arson. In 2008, someone threw a Molotov cocktail into the stately mansion while Perry and his wife, Anita, were in Europe. Three years later, DPS released tantalizing details about persons of interest—with links to anarchists—the agency was looking into. “We don’t believe in coincidences,” McCraw told reporters at the time. For a while, it looked as if McCraw would solve the crime of the decade, proving to his critics that DPS could still solve major criminal cases the old-fashioned way. But the case fizzled and remains unsolved sixteen years later.

If lawmakers were concerned that DPS had missed a step in solving a major crime, they didn’t show it. McCraw’s bosses—Perry and the Legislature—had bigger concerns than arson. By the time Perry ran for his third term, in 2010, border security had emerged as the sine qua non of Republican politics. (Sine qua non is Latin for “ain’t nuthin’ better.”)

Perry developed a fetish for militarizing the border—and McCraw was happy to oblige, overseeing the build-out of the nation’s first full-blown state border-security apparatus. Suddenly, DPS gunboats equipped with mounted .30-caliber guns were roaring up and down the Rio Grande while an army of state troopers flooded Texas border communities, especially in the Rio Grande Valley. “We’re using tactics and equipment that you will see in war zones,” a DPS captain told a documentary film crew in early 2012.

Six months later, a DPS sniper, operating from a helicopter, opened fire on a speeding F-150 near the border town of La Joya. He assumed, wrongly, that the truck was carrying drugs. Six Guatemalan migrants were hiding in the bed under a tarp. The sniper shot three of them, killing two. McCraw called the killing “very tragic” but insisted that the “recklessly speeding” truck posed a threat to an elementary school several miles away. Why was DPS the only domestic law enforcement agency in the country to allow cops to shoot at moving vehicles from helicopters? What responsibility did the DPS director bear for the consequences of waging a deadly war in Texas communities? GOP lawmakers seemed curiously uninterested in such questions. “There’s no need for a hearing,” said state representative Sid Miller, who was the chair of the Texas House Committee on Homeland Security & Public Safety. (Miller is now the state agriculture commissioner.)

Not long after Greg Abbott became governor, in 2015, he doubled down on border militarization. And then tripled and quadrupled. Today the Texas-Mexico border is arguably the most important stage in the world for American politicians—the photo op that has launched and sustained a thousand Republican careers. If the border was theater, the DPS director was the prop guy, stage manager, and supporting actor all in one.

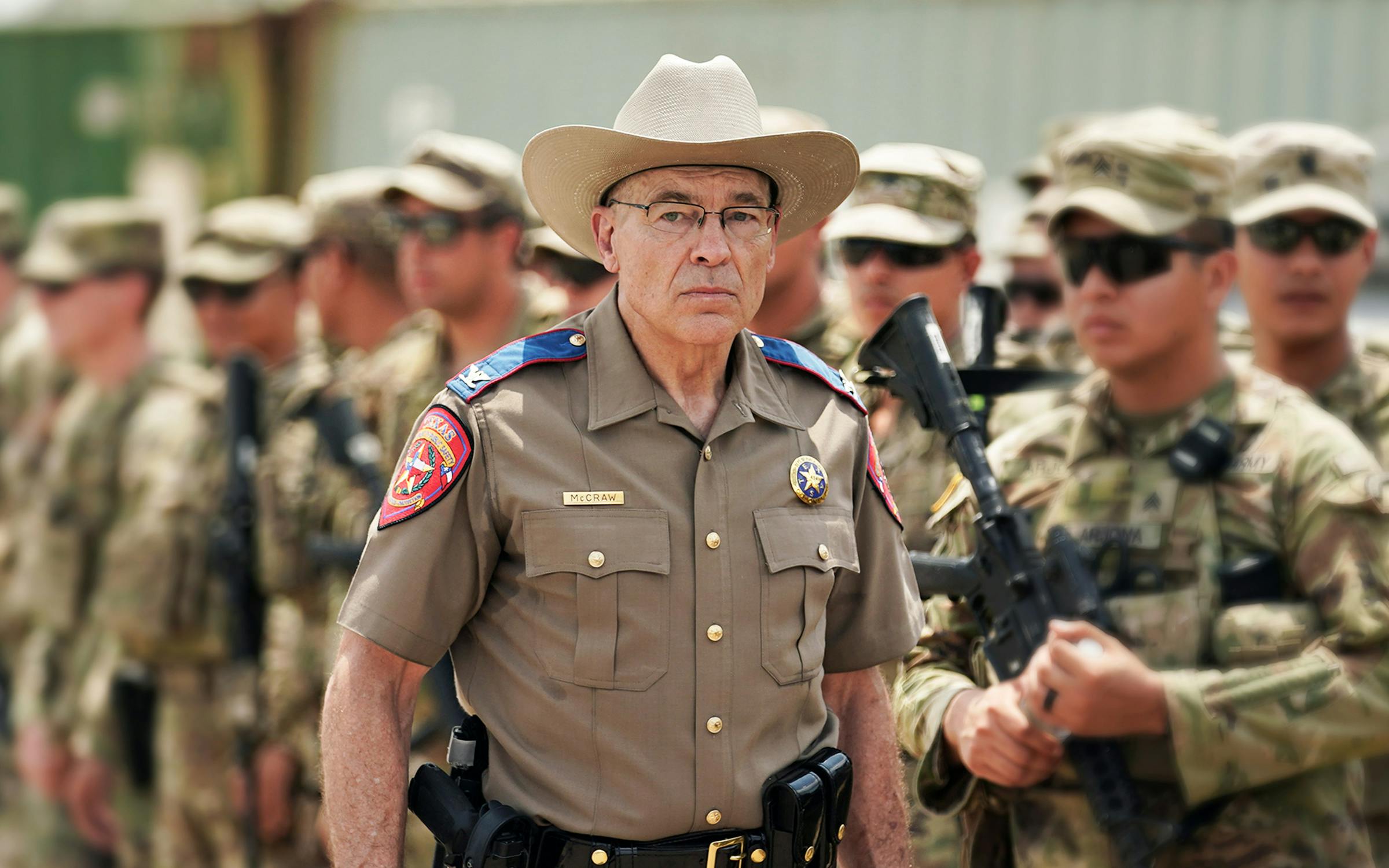

In front of TV cameras and at hearings at the Capitol, McCraw often appears in uniform—Texas tan, cowboy hat—and delivers a blizzard of homeland security–inflected cop talk about “force multipliers” and the “vertical stack” of “detection coverage” offered by drones, cameras, and “tactical” boats.

For a time, during Abbott’s first term, lawmakers and the press took a critical look at what the data said about the success rate of the state’s border operations. The results were dismal. What they found was that DPS was trying to take credit for drug seizures made by other agencies and classifying routine police work hundreds of miles from the border as part of its border efforts. DPS troopers seemed to spend a lot of their time writing tickets to RGV motorists in overwhelmingly Hispanic counties while neglecting traffic enforcement in other parts of the state. In a report to the Legislature in 2015, McCraw offered a utopian vision of success: “[The border] will be secure when all smuggling events between the ports of entry are detected and interdicted.” That could be achieved, the report said, with “the permanent assignment of a sufficient number” of troopers and Texas Rangers, along with a network of security cameras and surveillance aircraft.

On the face of it, this is a wild claim. Anyone with a passing familiarity with Texas’s 1,254-mile border with Mexico knows that catching every smuggler is the stuff of fantasy. But the accountability moment in the Legislature quickly passed. The politics of cracking down on a supposed border “invasion”—Abbott’s preferred term—were too good to let facts get in the way. Lawmakers showered the DPS director with more money, more responsibilities. In 2023, the Legislature gave DPS $1.2 billion for border operations, a 28 percent increase. Though apprehensions of unauthorized migrants have plummeted across the Southwestern border in recent months, there is no evidence that Texas’s efforts are responsible.

A measure of McCraw’s importance is the fallout—or lack thereof—from his agency’s handling of the Uvalde shooting. Lest we forget, close to 400 law enforcement agents, including 91 DPS officers, took more than an hour to confront the gunman responsible for the deaths of 19 fourth graders and 2 teachers. While children pleaded with 911 for help, heavily armed cops stood around in the hallways.

Afterward, various agencies and officers would blame one another. But in the moment, parents knew exactly what to do. Several tried to rush into the school but were physically blocked by police officers. One mother was arrested. Subsequent investigations found that the police prioritized their own safety over saving lives. In the aftermath of the shooting, high-ranking DPS personnel provided misleading information about the police response, with McCraw initially telling reporters at a press conference the next day that officers did immediately “engage” the shooter. This was, we would later learn, totally false. Abbott mused that “it could have been worse” without the “amazing courage” of the police. Abbott has never said who gave him the misinformation.

Soon after the shooting, the governor sternly admonished DPS and the Texas Rangers—the iconic agents are a unit of DPS—to get to the bottom of what went wrong. This was a bit like asking the livestock guardian dog to investigate how the fox got into the henhouse. What were the chances that McCraw was going to incriminate his own agency and, by extension, himself and the governor? The grieving Uvalde parents calling for his resignation might have earned the attention of the press, but he had the ear of the governor. For the next two years, DPS engaged in a tireless effort to point the finger at Pete Arredondo, the Uvalde CISD police chief, while casting a veil of secrecy over a mountain of information that could shed full light on the shooting. To this day, a coalition of media outlets is engaged in litigation to pry records loose from DPS, though at this point it’s not clear what else there is to learn about the ways the authorities failed those children and teachers.

In 2022, McCraw called the law enforcement response an “abject failure” and vowed to resign if DPS had “any culpability.” Subsequent investigations found plenty of culpability. A U.S. Department of Justice report blamed one Texas Ranger for not challenging Arredondo on the lack of urgency. The report also faulted DPS South Texas director Victor Escalon for failing to establish a perimeter outside the classrooms to preserve the integrity of the crime scene and for compromising the integrity of the crime scene by wandering around without purpose.

As for the investigation into the 91 DPS officers? To date, McCraw has done very little to hold his employees accountable. One trooper, Sergeant Juan Maldonado, was served with termination papers but quit before his firing was finalized. McCraw had initially tried to fire another Ranger, Christopher Ryan Kindell, but then, in early August, McCraw quietly reinstated him. According to the Austin American-Statesman, McCraw said the Uvalde County DA had requested the reinstatement after a grand jury declined to charge any DPS officers with crimes connected to the shooting. In reinstating Kindell, McCraw also avoided a public appeal hearing—and further scrutiny—into the roles played by high-ranking DPS officials.

McCraw, of course, did not resign. Instead, he got a raise. Last year his overseers at the Texas Public Safety Commission—all Abbott appointees—gave him a roughly $45,500 boost to his salary, bringing it to more than $345,000.

On the day of his retirement announcement, August 23, McCraw’s press team made available a cache of photos to commemorate his service. There’s a shot of McCraw riding in a DPS gunboat with Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick—a classic photo op. One of him serving food to troopers and guardsmen deployed to the border. But there’s one that seems to best capture the moment. Abbott is in the foreground of the photo, but he’s blurry. McCraw, looking contemplative in his uniform and cowboy hat, is the focus of attention. The same day those photos were released, Abbott kept the spotlight on his appointee. Steve McCraw, he said, is “a leader, visionary, and the quintessential lawman that Texas is so famous for—big, white cowboy hat and all.”

Brett Cross, the father of a boy who died at Robb Elementary, had a different take. “Good riddance,” he wrote on X. “You’re an embarrassment to this state. You’re an embarrassment to this country.”