A hundred years ago, the Tennessee General Assembly did one of the most important things in its history when it allocated tax dollars to buy land for what is now the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Ninety-nine years ago, the Knoxville City Council did one of the most important things in its history when it did something similar.

Considering how small the sums of money were and how popular the national park is today, it’s amazing how close both votes were.

When people tell the story of the national park, they usually start with the Knoxville residents who introduced the idea in the first place — most notably Anne and Willis Davis. To summarize a long story, the Davises got the idea of the Smokies as a national park when they visited some of the parks that already existed in the Far West. They were instrumental in starting the Great Smoky Mountains Conservation Association, which appealed to the nationwide committee that was looking for national park sites. Thanks to a letter writing campaign and to wonderful photos taken by Jim Thompson, the committee agreed to visit the Smokies.

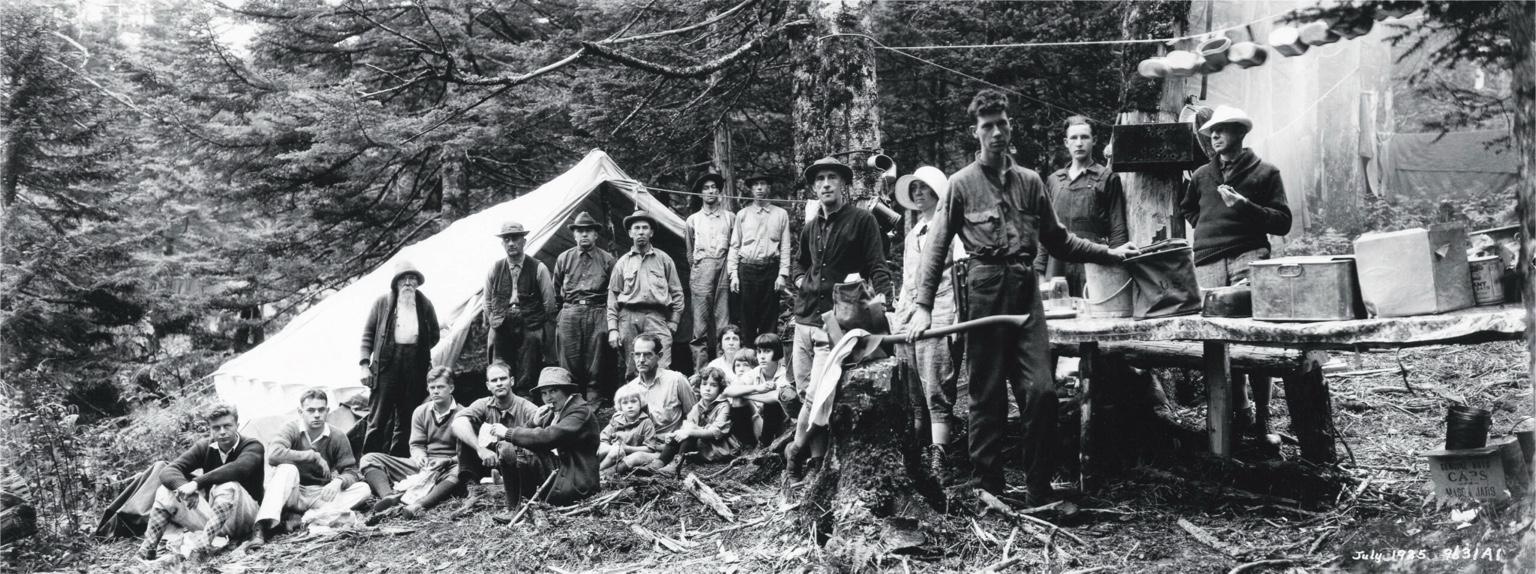

A group of people camp atop Mount LeConte in July 1925 -— a few months after the Tennessee General Assembly first allocated tax dollars to buy land in the Great Smoky Mountains.

Thompson Brothers photo, McClung Collection

On Aug. 6, 1924, committee members hiked to the top of Mount LeConte via a trail that had been cleared only a few days earlier. They saw Rainbow Falls, Myrtle Point and Cliff Tops, then spent the night in a log shelter that had just been built for them. On the way down, the group hiked past Alum Cave Bluffs.

Eight weeks later, the committee recommended that the Great Smoky Mountains be turned into a national park.

Carlos Campbell, a participant in the creation of the park, would later write a book called “Birth of a National Park in the Great Smoky Mountains.” According to Campbell, the national committee’s decision to recommend the Smokies as a national park was the first of nine steps toward the park becoming a reality. Most of the other steps had to do with money.

You see, just because a committee of the National Park Service recommended that the Smoky Mountains be turned into a national park did not mean that the federal government would buy the 515,000 acres that now make up the park. Someone else — notably, the taxpayers of Tennessee and North Carolina, private citizens and foundations — had to come up with the cash. That took years.

The first step in the fundraising effort was taken by the state of Tennessee. While campaigning for re-election, Gov. Austin Peay decided to make the Smoky Mountains acquisition one of his goals. (At that time, it wasn’t clear whether the land would be a state park, a national forest or a national park.) In the fall of 1924, Peay announced he had signed an agreement with W.B. Townsend of the Little River Lumber Company to buy the 76,000 acres that the company owned on the Tennessee side of the Smokies for $273,000.

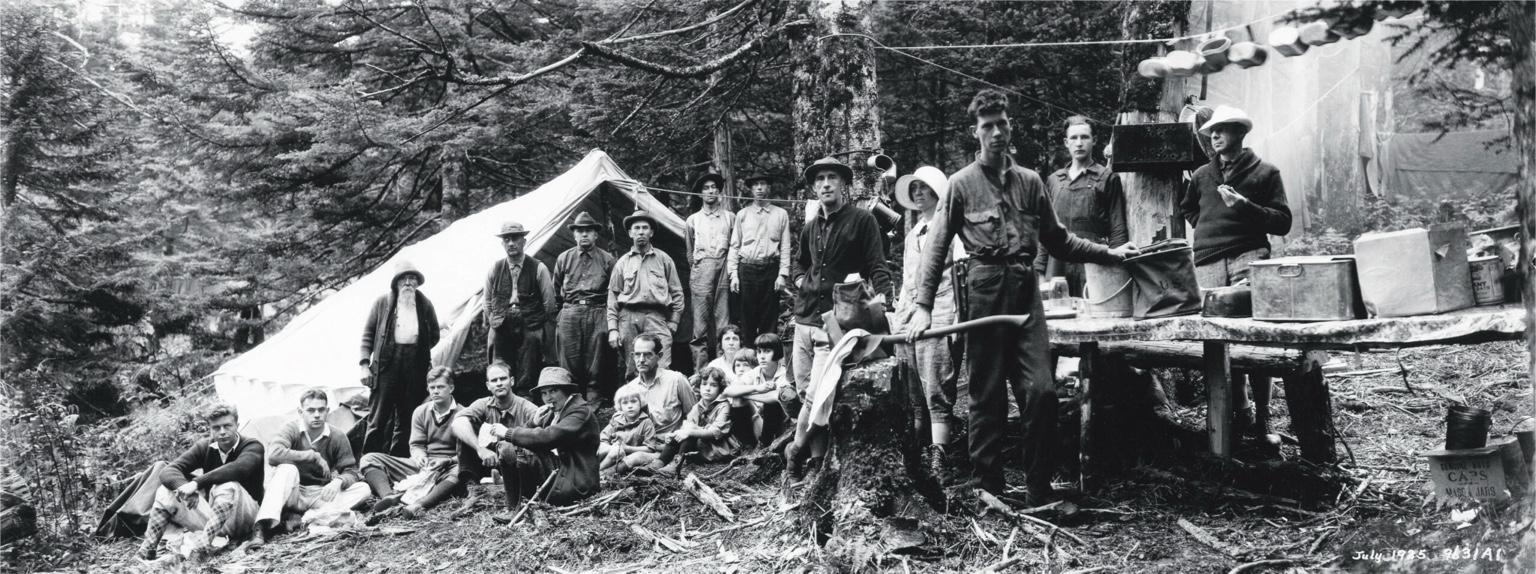

On March 17, 1925, members of the General Assembly posed for this photo after they disembarked from a train in Townsend. Afterward, they boarded private autos for a quick tour of the Blount County side of the Smoky Mountains.

Thompson Brothers photo, McClung Collection

Many newspapers didn’t think much of this idea. “One of the most preposterous schemes of the Peay administration,” is how the Nashville Banner described it.

Many lawmakers agreed with the Banner. Therefore, in January 1925, Gov. Peay told the legislature that the state only would be asked to provide two-thirds of the $273,000. The city of Knoxville — which wasn’t even in the same county as the proposed park — would pay one-third.

To encourage the legislature to support the measure, the Knoxville Chamber of Commerce raised $5,000 to fund a big trip. On March 17, all House and Senate members (and some of their spouses and secretaries) took a train to Townsend. From there they were taken in cars to Cades Cove, Little River Gorge and Elkmont — where they were wined and dined.

This junket seemed to work at first; the Smoky Mountains bill was passed by the Senate 20-13. But on April 8, 1925, it was rejected by the House, where only 45 out of 99 members voted for it.

However, exactly a day later, the same proposal passed when 13 of the House members who had voted against it voted in favor of it.

What happened? This is what the Knoxville News Sentinel tersely reported:

“After the vote Wednesday, (Gov.) Peay summoned several representatives to his office who had voted against the bill. They changed their votes when the bill came up Thursday.”

It wasn’t until a year later that the Knoxville City Council voted on its contribution of one-third of the $273,000. As the vote neared, Knoxville Mayor Ben Morton brought every council member into his office and tried to talk them into it. According to Campbell, who was witness to the process, six were willing to vote for it, but five were not since they had promised their constituents they would focus on local services.

“When the question was finally put to a vote, the results were six for participating with the state and five against it,” Campbell writes. “Seeing that they had lost their efforts to block the purchase, all five opponents changed their votes, and the official result was unanimous for the city’s participation.”

Granted, these two votes didn’t ensure that the national park would exist. There would be much larger financial hurdles along the way. There was a grassroots fundraising effort that raised more than $500,000 — some of it from Tennessee schoolchildren who gave a penny or a nickel. In 1927, the North Carolina legislature allocated $2 million for land acquisition, and the Tennessee legislature allocated another $1.5 million for land acquisition (financed by a gasoline tax). And in March 1928, the Rockefeller Foundation announced a gift of $5 million, ensuring the final success of the park movement.

So the $273,000 allocated by the combined state of Tennessee in 1925 and the city of Knoxville in 1926 ended up being a small part of what later was more like $10 million. But the Great Smoky Mountains National Park might not exist today if it weren’t for these two close votes.