That first morning, February 24, I had just woken up when I realised my heart was beating as fast as if I’d been exercising. For two minutes, I lay there listening: the roar of missiles outside, the thumping of my pulse in my ears, honking cars and alarms in the street.

I refused to admit that the worst I could imagine was happening. In the foggy morning twilight, I rose and tried to collect myself. Then I gathered my daughter’s things into a backpack.

She was crying as I rushed to put her most prized belongings into its small pouches. Little boxes of confetti, plastic food for the toy cat, tiny handmade notepads, Lego figurines, a few favourite stones. I was crying too. Now, I still feel as I did on the first day.

One day I got back to the outskirts of Kyiv a few minutes after the curfew started (it was 8pm then). The rules were strict. The soldiers at the checkpoint waved me on, but warned that I should drive at less than 10km/h, emergency lights blinking and with the interior light on and both hands on the wheel — if I wanted to get home alive. Every one of the next checkpoints I passed through, I did so with machinegun sights trained directly on my car.

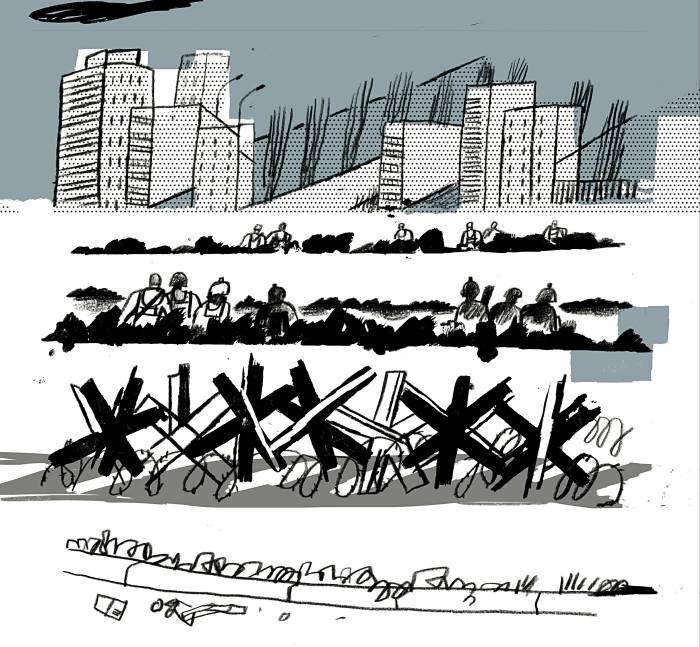

I crossed one of the bridges over a highway in the city. From there, my perspective was wide and I could see trenches next to fresh mounds of yellow earth. This reminded me of images from the world war. Soldiers in the trenches were preparing, getting into position, looking down the sights of their heavy machine guns. It is a very strange feeling when you see trenches next to typical Kyiv apartment blocks. This scene should have been disturbing, but the calm and bravery on the faces of the Ukrainian soldiers made me feel confident.

Lonely burnt-out, shot-out cars became a common sight on Kyiv roads.

I got stuck in traffic heading back to Kyiv with some journalists I’d taken to a village that had been attacked by a missile strike. It was a quiet and difficult six hours, at the end of which we’d moved three kilometres. Every five or 10 minutes a train of ambulances or military vehicles or buses with darkened windows and red crosses made of Scotch tape rushed by, honking to make way. I realised how many wounded soldiers must have passed just next to us while we inched forward.

I passed this scene often, much more than the others. It is on the way to the pool I go to. It opened non-officially at the beginning of April for a small number of people, myself included. Later, I overheard soldiers saying to each other, ‘Oh, there are our swimmers,’ indicating me and a friend of mine.

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first