[ad_1]

I know a poem can’t stop a tank. But the reverse is also true. As I’m writing this, the streets of China and Iran have been alive with infuriated, chanting crowds, so tired of being institutionally deceived and robbed of any personal agency or independence of mind that they are prepared to risk arrest and imprisonment rather than be silenced by regimes demanding obedience to lies.

“Culture wars” ought not to be confused with the laborious woke-baiting that has become the default position of populist media in the west. The women’s revolt in Iran is a culture war; Ukrainian resistance to the militarised fantasies of Russian imperialism is at root also a culture war, a refusal to accept Vladimir Putin’s contention that their nation’s language and history are a delusion. It is not accidental that one of the most powerful weapons that the actor-writer President Volodymyr Zelenskyy leading Ukraine has at his command is the gift of candid human communication.

Growing up in the 1950s, my baby-boomer generation assumed that the screamers of hate, the destroyers of culture, had gone with the war. “Well, boys,” our school history teacher confidently proclaimed around 1958, “we don’t really know what the rest of the 20th century has in store for us, but you can at least be sure of this: religious oppression and rabid nationalism are things of the past.”

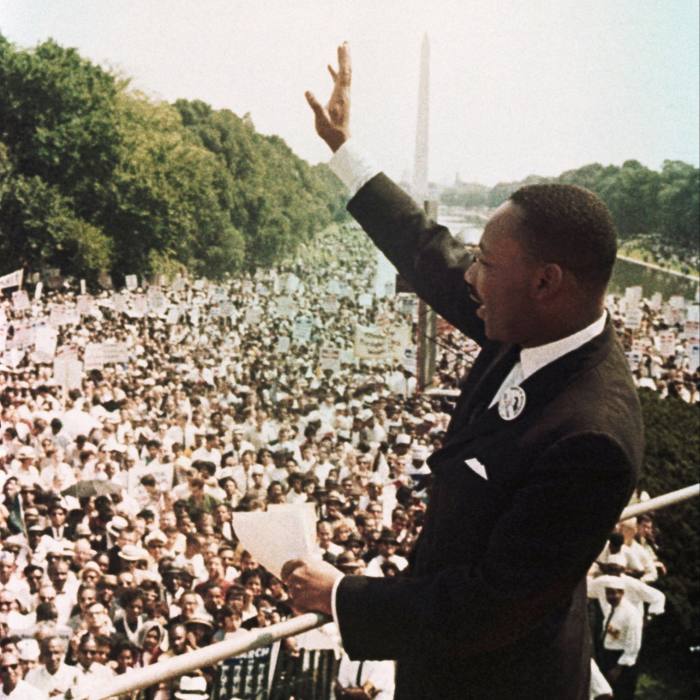

When, in that same year, Boris Pasternak won the Nobel Prize for Dr Zhivago, we thought that even the adamantine rock face of Soviet authoritarianism could somehow be cracked open just far enough for truth, memory and a faint breeze of freedom to be admitted. Even if Pasternak was demonised as an enemy of the Soviet people and forced to decline the prize, we believed that, sooner or later, light would return, as for a while, 30 years later, it did. Becoming a historian was, we thought, a vote of confidence in the victory of the Enlightenment. When the civil rights movement in the US flowered in the 1960s, we bought into Martin Luther King Jr’s conviction that “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice”.

Often enough, though, it snaps. Four days after he spoke those words in 1968 at the National Cathedral, Washington DC, he was murdered in Memphis.

My new BBC2 television series is the fruit of sombre, late-life reflection that the History of Now was prefigured in the History of Then; that what we had imagined to be things of the past have returned to shadow the present and future. Shrieking, whether online or on platforms, is back; hate is sexy and stalks the world as “disruption”.

So those old battles need to be refought, and with the help of the unlikely weapons that once opened eyes and changed minds: the soft power of culture — poetically charged words, images, music, all of which can, in some circumstances, exert a force beyond the workaday stuff of politics. Culture can do this because it can connect with human habits, needs and intuitions in ways that expose the inhuman hollowness of official propaganda.

What Václav Havel, in his most original and penetrating text, called “the power of the powerless” is capable of putting despotisms on the back foot, simply by being in sync with the simplest and most natural human instincts. Authoritarians can mobilise their heavy artillery of terror, torture, imprisonment and persecution; but in the end, Havel argued, they are not that well equipped to fight the asymmetric battle between lies and truth. Havel believed that the vast majority of people are not content to be forever walled within a prison of falsehood, where the price of material security and domestic safety is the unconditional surrender of personal freedom.

For a while — perhaps many decades — punitive disincentives against disruptive truth-speaking can prevail, especially when reinforced by visceral appeals to tribal loyalty: the demonisation of hate figures (such as George Soros) said to personify foreign manipulation. In the end what Havel calls the “trapped air”— a natural human wish to be able to speak one’s mind in a café, dress as one wishes (including visible hair), listen to unauthorised music, all the innumerable small acts of social defiance — can build into a rising tide of disgust.

When Czech police infiltrated the underground concerts of the Plastic People of the Universe in the 1970s — concerned, as their saxophonist Vratislav Brabanec remembered, that the music was some sort of “black illness” that would grow and generate disaffection — they only guaranteed more risible contempt. But there was a price. In 1976 the band was jailed for months, a wound Brabanec says you carry for ever. Why the wound? “Because I was innocent,” he says over his morning beer. “I was jailed for playing the saxophone.”

But from such ostensibly minor slaps of repression, barely registering on the scanner of state security, outrage can swell, gather and finally erupt into uncontainable mass disobedience. This happens, above all, when local family life, and especially the lives of children, become the collateral casualties of authoritarian brutality. In Iran, the death in September of Mahsa Amini, arrested for inadequate hijab covering, was taken as a cause for personal freedom by girls and women throughout the country. In China, the screams of a woman unable to escape a blazing apartment in Urumqi when the building door was barred and locked in an excess of Covid confinement, became the cries of an instantaneous mass movement of revolt.

Perhaps the most agonising detail in Picasso’s “Guernica” is the image of a mother cradling a dead child in her arms; the Pietà of civilian bombing. In Episode 2 of History of Now, one of the surviving children of the horrifying white supremacist bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, in September 1963, Dale Long, revisits the church, and his own traumatically poignant memories of the carnage. It was the spilling of children’s blood — among other murders and assaults — that led Nina Simone to compose the song of righteous rage “Mississippi Goddam”. When some southern states banned it for the profanity of its title, that only anointed the song as the jazz anthem of the civil rights movement.

In May 2008, a devastating earthquake in the western Chinese province of Sichuan took the lives of 69,000. More than 5,000 of the victims were children, buried in the collapsing structures of their schools. The losses were especially unbearable for parents who had had to obey the official one-child policy. The artist Ai Weiwei responded with a gesture of poignant mourning covering the walls of the Haus der Kunst in Munich in 2009: the 9,000 backpacks of “Remembering”, some of them spelling out in Mandarin the words of a grieving mother: “For seven years she lived happily on this earth.” But his reaction went well beyond tragic empathy, as searingly shown by another installation, exhibited later than “Remembering” but already under way at the time of that work’s conception.

When the earthquake struck, Ai was artistic consultant in the design team building the “Bird’s Nest” stadium for the 2008 Beijing Olympics (a role he subsequently repented, feeling compromised into an exercise in “patriotic education”). Familiar with the chronic corruption in kickback relationships with local and central authorities, Ai suspected that shoddy building practices had been responsible for the needless deaths of the children, a suspicion borne out when he visited the disaster site.

Meeting with a brick wall of silence from officials, not least about the families of the bereaved, Ai launched a citizens’ investigation mobilising 100 volunteers to hunt for information in the traumatised community; “to remember the death and show concern for the living; to shoulder responsibility for finding out every child’s name and placing it on record . . . ”

The affronted authorities responded with arrests, confiscation of the volunteers’ notes and erasure of phone photos. But none of this stopped Ai from conceiving and executing the most powerful work of contemporary art to arise from calamity: at once a poetic meditation, a document of what happened, who and what had been responsible, and an act of resistance against oblivion. (That last resolution Ai inherited from his father, the poet Ai Qing, who suffered the depths of degradation during the Cultural Revolution and shared the hole in the ground that was his prison dwelling with his son, who still keeps a photo of the dugout on his phone.)

Scouring scrapyards, Ai recovered nearly 200 tons of buckled rebars: the steel reinforcing rods meant to maintain the integrity of concrete, which had failed so disastrously during the earthquake. Each of them was hammered (200 beats for each rebar) by a small army of workers and assistants back to factory-fresh form, giving the title “Straight” to a work that was about the obstinacy of the truth. Dimly, the authorities began to understand what they were up against and reacted with their routine savagery. In August 2009, when he was trying to testify on behalf of one of the volunteer investigators, Ai was waylaid in his hotel room and beaten so brutally he needed surgery to treat a brain injury caused by the assault.

None of this slowed the work down. While he was recovering, the piece came into shape. Hundreds of the straightened rebars were laid out on the floor, piled up in places to mimic the heave of a rolling, seismic wave of death. You stand before this assemblage — beautiful and terrible — and feel shaken, unsafe. On the gallery walls surrounding the piece Ai pinned lists of names — thousands of them — of the dead, marked in memory despite the best efforts of Chinese officialdom to consign them to oblivion. “Straight” is the “Guernica” of our young, bloodied century, and no textual history could possibly recover, as this masterpiece does, the enormous weight of the event’s catastrophe.

But the lightness of art can shift history too, subtly, yet decisively. I suspect the last thing David Hockney would want for his California paintings of the 1960s would be for them to be seen as manifestos of gay liberation. But, over time, they worked transformational magic on homophobia nonetheless, possibly because they were, in the first instance, celebrations of personal pleasure bathed in Angeleno radiance. Formally, “Peter Getting Out of Nick’s Pool” (1966) is not just a perfect composition but a candy-box history of representational styles: Modernist angularity broken by spaghetti-ripples, but at its centre the original Greek coinage of beauty itself made tangible in the male nude. It is a very clever picture and yet also disarmingly artless: an oasis of innocent joy delivered to a dark, furious and still largely unwelcoming world. Who could possibly take exception?

Nearly six decades on, the answer is, alas, plenty of folk. Sixty-eight countries around the world criminalise homosexual acts, some with capital punishments including stoning. Among the prohibiters is Qatar, where police have obliged football fans at the World Cup to remove any item of clothing (or flag) with rainbow decoration and where Fifa threatened to penalise team captains should players have the effrontery to wear “One Love” armbands. It’s safe to say that the father of the suspected shooter at the LGBTQ nightclub in Colorado Springs who killed five and wounded 18 last month, whose main concern was whether his son might be gay, is probably unmoved by the swimming pools of David Hockney.

Of course, there are limits to what activist art and culture can do. More heartening, however, are the demonstrations — from one end of the world to the other — of how their eloquence and visionary power can actually affect contested outcomes.

There’s no doubt that Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, originally published in 1985 but given new life in popular culture by television, played a part in mobilising votes in reaction to the Supreme Court’s overturning earlier this year of Roe vs Wade’s protection of abortion rights. Referendums held to restrict abortion rights further all failed, even in conservative states such as Montana and Kentucky. Artists and writers are under no obligation to be political, Atwood says in an interview for History of Now, but none can escape the imprint of their times. “I write about potentially unpleasant futures,” she says, “in the hope that they will not become real.”

When the worst does materialise, some writers become even more determined to have their voice heard. Rachel Carson was herself dying when Silent Spring was published in 1962. Her books on the natural history of the oceans had become million-copy bestsellers precisely because they translated scientific knowledge into poetically rich storytelling. As fiercely analytical as was her attack on the effect of chemical pesticides on the food chain, it was the opening fable of that birdless silence falling on the countryside that gripped the reader and changed minds.

My father, a great storyteller in his own right, understood the uniqueness of Carson’s marriage of literature and science when he read passages from Under the Sea Wind to me while we were still living on the Essex coast. Swimming along with Scomber the mackerel, I understood, even then, that humans were not a breed apart from nature but an inseparable part of it. Which was the lesson, as it turns out, on which all our futures now depend.

All the stuff of mainstream history — wars, revolutions, economies — is becoming a subset of the engulfing, elemental question: the fate of the earth; what humans have done to it and what they may yet do to repair and redeem the damage. We are running out of time. But what we have not yet exhausted is what, in the end, makes us human: the great storehouse of visionary imagination. If, at the eleventh hour, we have what it takes to pull off the greatest escape act in the human story, it will not be databanks or algorithms that will have got us there, but something like a poem, a novel, a painting or a song.

‘Simon Schama’s History of Now’ is airing on BBC2, Sunday December 4 and 11, 9.30pm; all episodes are available on iPlayer. He is an FT contributing editor

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on Twitter

[ad_2]

Source link