BBC

BBCRihab Faour fled her home. Then she fled again. Then a third time. Then a fourth. And by the fourth time, a year after the first, she had been fleeing Israeli bombs for so long that nowhere in Lebanon felt safe.

Her journey had begun in October 2023, when Hamas attacked Israel. That prompted Hezbollah, the Lebanese political and militant group, to fire rockets into Israel and Israel to retaliate by bombing southern Lebanon.

The Israeli bombs fell close enough to Rihab’s village that the 33-year-old and her husband Saeed, an employee of the municipal water company, gathered their daughters Tia, eight, and Naya, six, and fled to Rihab’s parents’ house in Dahieh, a suburb of the capital Beirut.

In Dahieh, for a while, life went on almost as normal, with the exception that Naya and Tia missed their friends, their own beds, their toys and all clothes they had had to leave behind.

Most of all they missed going to school, which had been replaced by online learning. They were excited when, back in August, Rihab enrolled them in a new school in Beirut and took them to buy brand new school uniforms.

Joel Gunter/BBC

Joel Gunter/BBCBut before their first day could arrive, Israel expanded its bombing of Lebanon to include parts of Beirut, particularly the Dahieh suburb that the family now called home.

Israel was assassinating senior Hezbollah figures in the suburb, but it was using large, bunker-busting bombs, each capable of destroying a residential building. In some strikes, Israel dropped dozens of these bombs in one go and flattened entire city blocks.

So the Faour family packed up and fled again, this time to a rented house in another Beirut neighbourhood, Jnah. After a powerful air strike in Jnah, they moved to Saeed’s parents’ house in the neighbourhood of Barbour. There, they lived with 17 others in a single house – people piled on people.

For Tia and Naya though, now nine and seven, it was a rare joy to be surrounded by their cousins day and night. So much so that even when Rihab’s father, a retired Lebanese army sergeant, found a rental apartment in the Basta neighbourhood just for the four of them, the girls did not want to go.

Joel Gunter/BBC

Joel Gunter/BBC“Naya begged us to stay there with all the family,” Rihab recalled. “We told her we just had to go for one sleep in this new house, then we would come straight back to the family and to all the children.”

And she offered the girls a bargain – come to stay at the new apartment and you can choose your dinner. So on the way home they stopped for rotisserie chicken and other treats from the shop, and at about 7.30pm, with the streets still alive with people, the family pulled up to a rundown building in Basta in central Beirut.

Back in 2006, during the previous war between Israel and Hezbollah, the bombing was confined to certain areas of Lebanon – the south, Dahieh, and some infrastructure targets. This time, as senior members of Hezbollah spread out around the country, Israel bombed them where they went.

This brought bombs to places previously thought safe, including parts of central Beirut.

Joel Gunter/BBC

Joel Gunter/BBCNone of that was weighing on Tia and Naya as the family unloaded their belongings into the new apartment. For now, the girls were more concerned with returning to their cousins at the earliest opportunity.

Unlike Saeed’s parents’ house, the new Basta apartment had running water and a generator for electricity. The girls were happy when they saw that the family finally had their own space. Rihab and Saeed relaxed a little. Most likely, there would have been an Israeli drone buzzing overhead, but the sound had become so common over Beirut that it was possible to tune it out.

Rihab put the food and treats on the table. “We sat down to eat and we were talking and laughing,” she said. “And that was it, my last memory of them.”

Joel Gunter/BBC

Joel Gunter/BBCThe bomb was a US-made Jdam. It hit the building on 10 October at about 8pm, half an hour after the family had arrived. It levelled all three storeys and destroyed parts of adjacent buildings and cars, and killed 22 men, women and children, making it the deadliest strike on central Beirut since the beginning of the fighting a year earlier.

The Israeli military issued no warning ahead of the strike, so the building was full of people. Israel was reportedly targeting Wafiq Safa, the head of Hezbollah’s co-ordination and liaison unit, but Safa was never reported to be among the dead. He had either survived, or he wasn’t there to begin with. The IDF declined to comment on the strike or the lack of a warning ahead of it.

Rihab woke up in Beirut’s Zahraa Hospital, unable to move. Her back and arm were badly injured and she needed at least two operations. She drifted in and out of consciousness. Everything in her mind between laughing with her daughters at dinner and waking up in the hospital was blank.

Joel Gunter/BBC

Joel Gunter/BBCWhile she lay there that night, her family searched Beirut’s hospitals. By midnight, they knew that Saeed and Tia were dead. DNA tests would be required to confirm that Naya had been killed, as well as another girl her age brought to the same hospital, because their injuries prevented straightforward identification.

Rihab’s doctors advised the family not to tell her any of this. They were worried that, still facing significant surgery, the news would be too much for her. So for two weeks, as she underwent and then recovered from her operations, her mother Basima reassured her that Saeed and the girls were being treated in different hospitals.

But Rihab sensed that something was wrong, and she began to insist on seeing pictures and videos of the girls. “She could feel it in her heart,” Basima said.

Eleven days after the strike, the DNA test confirmed that Tia was dead, and on the 15th day a hospital psychiatrist told Rihab that Saeed and the girls were gone.

Joel Gunter/BBC

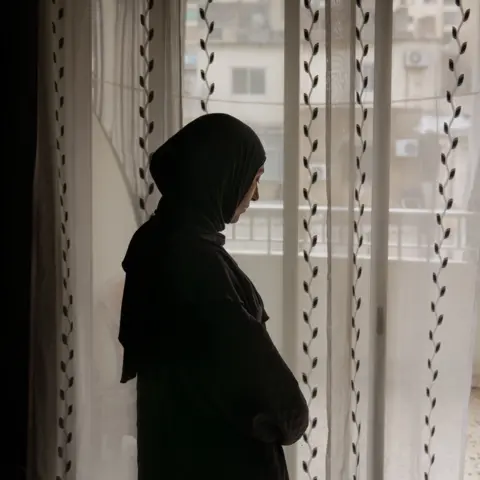

Joel Gunter/BBCSix weeks later, Rihab was sitting in a stiff plastic chair in an apartment in Beirut, her eyes dark and her face drawn. She was still recovering from her surgeries – to install eight screws into her spine and another three into her arm. She had been lying down for a long time, and now she was trying to sit up more and to walk a little, though every movement caused her pain.

Naya’s eighth birthday had been four days earlier. Rihab was passing her time “either crying or sleeping”, she said. But she wanted to talk about her family.

“Naya was very attached to me, she followed me wherever I went. Tia loved her grandparents and she was happy if I left her with them. Both of the girls loved drawing, they loved playing with toys, they missed going to school. They would play teacher and student together for hours.”

Above all they loved to watch videos together on TikTok. Rihab and Saeed thought they were still too young to post their own videos online, so Rihab would film them dancing and playing and tell the girls she was posting them on the app, which seemed to satisfy them, for now.

Saeed had come into Rihab’s life in 2013. Rihab was raised in Beirut but her family would visit the village of Mays El Jabal in the summer, because the air was cooler there and the village was surrounded by countryside, and that summer she met Saeed through mutual friends.

Rihab completed her undergraduate law degree and began studying for a masters, but the couple became engaged and then married, and soon Tia was born, so Rihab put her budding law career on hold.

Now, in the midst of her loss, she has tentatively begun to think of studying again. “I am going to need something to fill my days,” she said.

Joel Gunter/BBC

Joel Gunter/BBCSaeed and Tia were buried the day after they died, by Rihab’s father and uncles, in temporary wooden caskets in an unmarked grave in Dahieh. Two weeks later, the men of the family dug again in the same spot and buried Naya. Rihab’s uncle placed two sprigs of artificial cherry blossom atop the grave, for the two girls, and later someone else laid a wreath for a stranger buried beside them.

Then an Israeli air strike hit the building directly adjacent to the cemetery and the resultant blast wave and debris smashed gravestones and churned up the earth around them. About the same time, another Israeli air strike hit the family home in Dahieh, destroying several items Rihab had wanted to keep, including two new, unworn school uniforms.

Not long after that, it was all over. A ceasefire announced last week allowed thousands of displaced people to stream back to their villages in the south of Lebanon. Rihab and Saeed’s village was heavily bombed by the Israelis and their family home there destroyed, her uncle said, but Rihab cannot return home anyway, because she will be in a backbrace for several more months and cannot travel.

As joy spread through Lebanon at the news of the ceasefire, new pictures emerged of Wafiq Safa, the reported target of the bomb that killed Saeed, Tea, Naya and 19 others. Safa had not been seen in public since the strike, but he appeared to be alive and well.

Additional reporting by Joanna Mazjoub