In quiet corners of suburban England lie two private companies that have skyrocketed to multi-billion-pound valuations in less than a decade, while barely registering in the public consciousness.

Belron and The Access Group are both long-established businesses that are far from the image of hot start-ups with revolutionary products. Located on the outskirts of Egham in the south-east, Belron repairs and replaces car windscreens; The Access Group, based just outside the Midlands town of Loughborough, sells back-office software.

Over the past six months, investors have given both companies valuations that place them among Britain’s biggest companies — €21bn for Belron and £9.2bn for The Access Group. Belron’s valuation has climbed 600 per cent since 2017 and The Access Group has risen an eye-watering 3,800 per cent since 2015.

Yet neither group has been exposed to the cut and thrust of public markets. Instead, their valuations were set in a new and controversial type of transaction that is fast becoming the private equity industry’s hottest trend in the US, UK and several other markets — deals in which a buyout group in effect sells a company to itself.

Such deals have partly been a consequence of the tidal wave of cash that has flooded private markets during the long era of low interest rates. As that era comes to an end and a downturn looms, these deals are set to become more attractive than ever for private equity groups with companies to sell.

The deals — a way for buyout groups to return cash to their original investors within a pre-agreed 10-year time period, without the need to list companies or find outside buyers — have been growing in popularity since the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, when a market freeze prompted a search for new options.

But selling companies to themselves risks putting the industry on a collision course with a range of different groups.

Some of private equity’s own investors complain that the deals can in some cases serve to enrich buyout billionaires and multimillionaires at the expense of their pension fund clients by enabling them to keep levying fees. The Securities and Exchange Commission wants to reform the market, requiring more checks that valuations are fair.

Equity market investors are becoming increasingly vocal about how private markets value companies. Vincent Mortier, Amundi Asset Management’s chief investment officer, said this month that parts of the buyout business “look like a pyramid scheme” because of “circular” deals in which companies are sold between private owners at high valuations.

Speaking privately, some pension funds are frustrated. “This is wonderful for the [buyout groups]; it’s one of the best things they ever discovered,” says one pension fund’s head of private equity, who asked not to be named.

But “it’s one of the worst things” for their investors, he adds. “The pie is getting bigger” as private equity balloons in size, he says, but “more of the pie is going to the [private equity firm] and less is going to [its investors].”

A structural change

In the private equity industry, selling a company to yourself can take multiple forms, and dealmakers struggle to decide what to call the process. It is sometimes labelled a “continuation fund” or even, in the industry’s often-inscrutable jargon, a “GP-led secondary” or “adviser-led secondary”. A common feature is that a stake in one or more portfolio companies is sold from one fund to another, both of which are controlled by the same private equity firm.

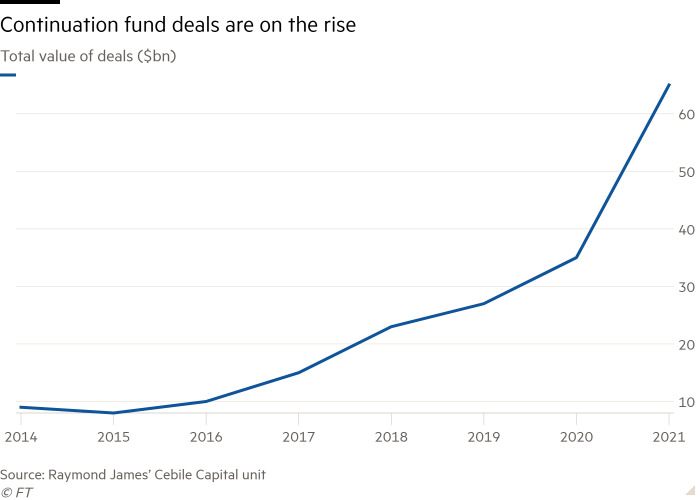

Deals worth $65bn were carried out this way last year, up from $27bn in 2019, according to Raymond James’ Cebile Capital unit.

Industry figures expect that number to keep rising. “It’s a structural change, a structural addition to the private equity ecosystem, [and] it’s here to stay,” says Sebastien Burdel, a partner at Ares who focuses on the asset manager’s secondaries business.

“In an environment where exits [sales of portfolio companies] are going to slow for a period of time, having that extra tool . . . is going to be increasingly attractive.”

Windscreen repair and replacement company Belron, which operates internationally under brands including Autoglass and Safelite, was valued at €3bn in 2017, when US buyouts group Clayton, Dubilier & Rice agreed to buy a 40 per cent stake.

Since then, its core earnings had roughly trebled as margins had risen, in part because new technology had made windscreens more complex and more expensive, a person close to the company said.

In December last year, CD&R sold a minority of its holding to a trio of new investors, Hellman & Friedman, BlackRock’s private equity business and the Singaporean sovereign wealth fund GIC. The deal valued Belron at €21bn, almost 20 times its earnings, roughly twice the multiple that CD&R had originally paid, the person said. CD&R then sold the rest of its stake to its own special purpose vehicle, which it set up especially to own the Belron stake, at the same valuation.

The Access Group, whose clients include the Beatles Story tourist attraction in Liverpool and the Latymer public school in London, has been repeatedly sold between funds belonging to its private equity owners TA Associates and Hg, since TA first bought a stake in 2015 at a valuation of £231mn.

Deals in 2018, 2020 and June 2022 saw its valuation soar to £1bn, £3bn and £9bn, respectively. That leaves The Access Group, which has itself been on a dealmaking spree to snap up about 40 companies in the last five years, with a higher valuation than the FTSE 100 software provider Sage Group — a UK rival whose shares have tumbled this year.

The company’s owners “don’t feel any pressure to go out and list this business now or in the future,” says a person close to the deals. “There’s plenty of private capital available — they don’t need to go public in order to be able to generate returns for investors.”

Hg says its investors were always given the chance to block the deal completely, and that a third-party investor would set the price in any company it was selling between its own funds.

Flush with cash

In order to buy their own companies, private equity firms often raise money from a little-known group of specialist investors known as “secondary funds”. CD&R raised some of the $4bn it used to purchase its own Belron stake from this market, though The Access Group deals did not tap it.

Secondary funds raise cash from pension and sovereign wealth funds — the same institutions that invest in buyout funds. They are flush with cash, having raised $78bn in 2020 and $37bn in 2021, a jump from $24bn the previous year, according to the Raymond James data.

Many of these funds are in fact run by units of private equity firms themselves, with Blackstone, Ardian, Carlyle and Ares among those that have significant so-called secondaries businesses. The upshot is that these private equity groups are providing the funds that make it possible for other buyout groups to sell their own companies to themselves.

For these groups, “the idea is, you can create a greatest hits album” by buying into vehicles set up to own private equity’s best-performing companies, says Tony Colarusso, global head of private capital advisory at Morgan Stanley.

French buyout group Ardian has a $19bn secondaries fund and Blackstone was on course to raise about $20bn for its latest such vehicle, chief operating officer Jon Gray said on an earnings call in October.

Others have spent the last two years racing to either set up their own secondaries businesses, or acquire existing ones. Ares struck a deal last March to buy Landmark Partners, which finances continuation fund deals among other specialist transactions, and CVC Capital Partners agreed to buy Glendower Capital in September. Asset manager Franklin Templeton, better known for its mutual fund products, bought the secondaries specialist Lexington Partners for $1.75bn in November.

Brookfield chief executive Bruce Flatt said in 2020 that the private equity secondaries market “could be a $25bn to $50bn business for us” and was “a meaningful extension” for the firm, while Apollo recruited three senior BlackRock executives in April to lead its push into the market, and TPG has hired specialists from the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, Pantheon and Landmark as it seeks to do the same.

Both sides of the deal

As the market grows, however, multiple concerns are being raised about how these deals work in practice.

The most frequently expressed and perhaps most obvious is the conflict of interest that occurs when the same buyout group is on both sides of a deal.

“When everything is said and done, it will either turn out to be a better deal for the buyer or for the seller,” says a senior executive at a major buyout group that has not sold any companies to itself. “We don’t want to get into that position.”

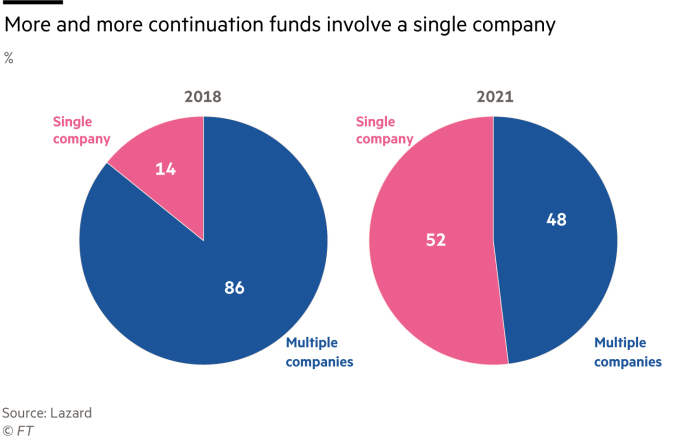

Unlike in the Belron case, private equity firms often arrange continuation fund deals without running a competitive sale process in which corporations or rival buyout groups are invited to bid.

In those deals, the pension plans and other investors in the older fund selling the company say they cannot be sure they are getting the highest-possible price.

Five of the biggest continuation funds

$4bn

December 2021

Private equity group: CD&R

Portfolio company: Belron (Vehicle glass repair and replacement)

$3bn

July 2021

Private equity group: General Atlantic

Portfolio companies: Argus Media (Market data and business analysis); Red Ventures (Media, including CNET and Lonely Planet); Sanfer (Pharmaceuticals); Howden Group Holdings (Insurance)

$2bn

July 2021

Private equity group: New Mountain Capital

Portfolio companies: Western Dental (Medical services); Information Resources (Data analytics and market research); Avantor (Medical products and services)

$1.8bn

March 2022

Private equity group: Accel KKR

Portfolio companies: Abrigo; Vitu; Kerridge Commercial Systems; Energy Services Group; IntegriChain; ClickDimensions; TrueCommerce (all specialist software providers)

$1.7bn

January 2021

Private equity group: Audax

Portfolio companies: Innovative Chemicals Products Group; Justrite Safety Group (Manufacturing); 42 North Dental (Medicine); TPC Wire & Cable Corp (Manufacturing)

Source: Raymond James’ Cebile Capital unit

Data on sale prices would appear to confirm their worries. Forty-two per cent of continuation fund deals value the underlying company at less than the private equity firm had told the investors it was worth, according to research by Raymond James. Half value the companies at the same amount the private equity firm had estimated it to be worth and only 8 per cent are sold at a premium.

“You should get honest price discovery for these [investors],” says Jeffrey Hooke, a lecturer at Johns Hopkins’ Carey Business School. Most pension funds “don’t have the guts or the resources to challenge these prices [but] they’re representing hundreds of thousands of retirees living on fixed incomes”.

Buyout groups respond that they give investors in their original fund a choice: they can become an investor in the continuation fund or walk away. But the idea of a real choice, with an option for the deal to be called off, “is a bit of a pink unicorn that never really exists”, according to a managing director at an investment firm that allocates cash to buyout groups. Several pension fund executives said they were given too little time to make the decision.

The SEC is now scrutinising the model, part of a wider review of disclosure in the private equity industry. It plans to require buyout groups to commission a fairness opinion when they sell companies to themselves, and to disclose any “material business relationships” it has with the company providing the opinion.

‘Super carry’ deals

Private equity firms and their dealmakers can reap great financial rewards from continuation funds— by charging their investors higher fees and taking a higher share of the profits.

“Capturing a larger share of the fee pool” is “economically interesting” for buyout groups and is one of the driving forces behind their use, says Bernhard Engelien, co-head of European private capital advisory at the investment bank Greenhill.

The complicated economics behind private equity funds can obscure how this works. In simple terms, standard buyout funds charge their investors, such as pension funds, an annual management fee of between 1.5 and 2 per cent of the money they have committed to the fund.

But once a fund has finished its so-called “investment period”, when it is buying companies — roughly its first four to six years — it stops charging fees as a percentage of the money committed. Instead it charges fees as a proportion of the money used to buy the companies that the fund has not yet sold. The effect is that buyout firms make far less in management fees in the later years of a fund’s 10-year life.

Selling companies in an older fund to a continuation fund lets the buyout group revive the flagging fee base. The new vehicle charges fees as a proportion of the amount it invested in a company — invariably a higher sum than the older fund paid.

Then there is the carried interest: the 20 per cent share of profits on successful deals that can provide lucrative, and tax-advantaged, payouts to buyout executives.

Dealmakers can receive those so-called “carry” payouts twice, once when a company is sold to the continuation fund and again when that vehicle later sells it, though they usually put most of the first payout back into the new vehicle.

Carried interest is typically only paid out after a private equity fund hands a pre-agreed return to its investors, often around 8 per cent. If a fund looks to be likely to miss that target but contains a star company from which dealmakers would otherwise have reaped a large profit share, shifting the high performer into a new fund enables dealmakers to receive the payouts.

Better still for the dealmakers, in some cases they can negotiate so-called “super carry” on the continuation fund. Some use a tiered carried interest model where, if the company in the new vehicle generates less than a 20 per cent return for investors, the dealmakers would receive less than the standard 20 per cent profit share. But if it generates more, they can receive much more.

In a survey of the specialist investors that finance continuation fund deals, sixty-eight per cent said they had funded at least one with a “super carry” provision, according to Raymond James. Those usually allow buyout executives to keep up to 25 per cent of the profits but in some cases stretch as high as 30 per cent.

“[As a buyout group] you set the price for your deal, you sell it to yourself, you crystallise a bunch of the carry, and now you’re charging more fees on the same company you already owned,” says the pension fund executive. “In the old days you would just keep managing this for a lower fee, without carry.”

Even the Institutional Limited Partners Association, which represents the investors whose money private equity firms manage and which is not known for punchy public criticism of the buyouts business, has spoken up.

“As LPs [investors] in the original funds . . . the secondary is often structured in such a way that the benefits disproportionately accrue to the adviser [the private equity firm],” it said in a submission to the Securities and Exchange Commission.

At the heart of the deals is a broader issue that is becoming more significant as stock markets tumble. Companies owned by private equity groups are facing the same pressures as their listed peers, as interest rates rise, supply chains struggle and an economic downturn looms.

Critics of the industry believe some of these deals could be a way of hiding from this reality.

“It is a myth that private equity investments are good investments to have in times of stock market turmoil,” says Eileen Appelbaum, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research. Continuation funds mask “an unpleasant truth”, she says, by enabling the private equity industry to keep doing deals that shelter their companies from valuations in the public markets.

The question, she adds, is for how long that can continue.