The United States is facing crunch time for its Social Security program: In a decade, according to the latest projections, the trust fund for this massive safety net for retirees and the disabled will be depleted, triggering sharp cuts to benefits unless lawmakers take action to bring more money in, spend less or do both.

So far, neither President Biden nor former president Donald Trump has made shoring up Social Security central to his presidential campaign. But some American policy experts are looking abroad for lessons.

Many countries face the same pressures as the United States: Their aging populations have fewer workers to support retirees. But quite a few countries spend more on their public-pension programs than the United States does, offering more generous benefits and lower retirement ages.

Making international comparisons is complicated because of economic, political and demographic differences. But Wellesley College economist Courtney Coile, who has long studied public-pension systems around the world, notes that many countries have enacted policy changes in recent years, while Social Security is largely unchanged since the last major overhaul in 1983.

In part, Coile said, that’s because the 1983 reform helped lock in long-run savings, so the United States has spent less over time. “One big point of difference is the benefit level is less generous … than in a bunch of countries,” she said.

Here are five charts that show how Social Security compares with retirement systems around the world.

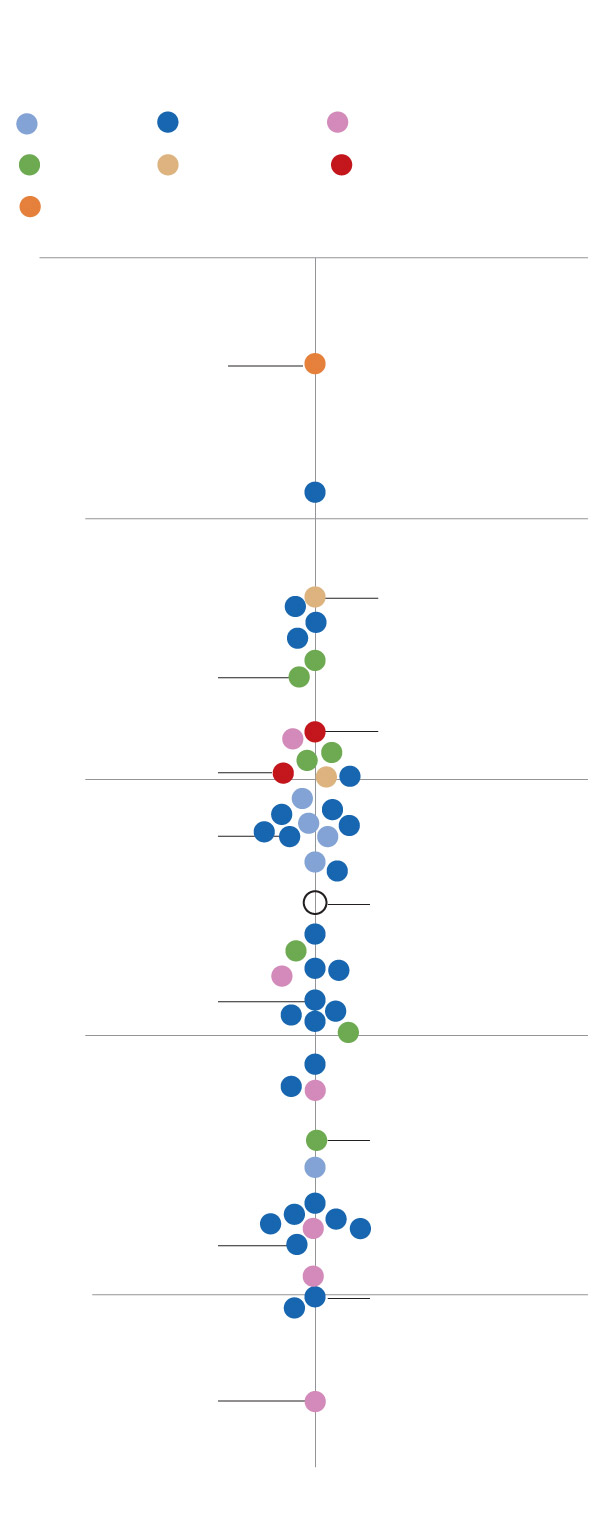

1. Americans typically retire later

In the broadest terms, the financing for Social Security works the same way as it does in pension systems around the world: Workers, employers or both pay a portion of the salary as a tax into a government fund during the years of employment. Then, when those workers retire, they are entitled to benefits via a regular check. So one way to collect more and spend less on public pensions is to raise the age at which people start receiving those benefits.

The U.S. statutory retirement age is 66 or 67, depending on your birth year, higher than all but nine countries. Worldwide, the median is 61. In some countries, workers can choose to retire at a slightly younger age — in the United States, as young as 62 — and take lower benefits. Or you can wait a few years in exchange for more generous checks.

Several countries have adjusted their retirement ages upward in recent years or have plans to do so. Even so, their workers generally retire younger than Americans. Such reforms are often a political minefield: In France, for example, people furiously protested in the streets over President Emmanuel Macron’s proposal to raise the retirement age from 62 to 64.

For their part, Trump and Biden have both campaigned on a pledge not to cut Social Security benefits, including by raising the retirement age.

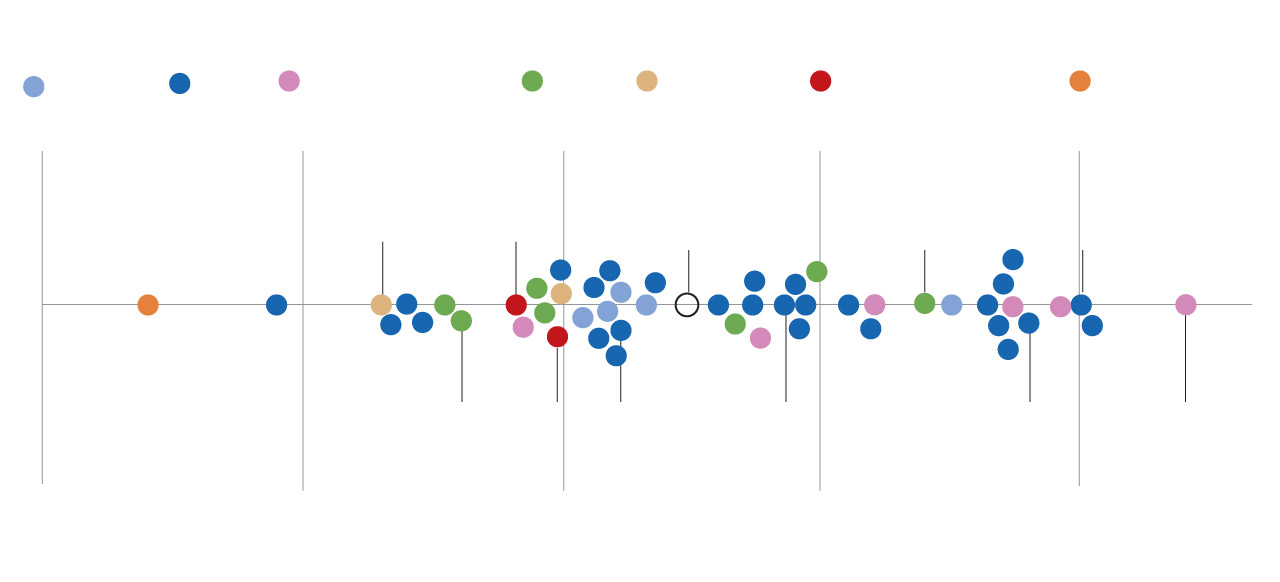

2. Social Security benefits are modest compared with elsewhere

When workers retire and start collecting benefits, the change in their standard of living can vary tremendously. Social Security only replaces about 40 percent of the average American’s paycheck, so people who rely primarily on Social Security often see a steep drop-off in monthly income.

Percent of pre-retirement income replaced by pension

Percent of pre-retirement income replaced by pension

In many other countries, benefits are more generous and come closer to fully replacing workers’ paychecks. Americans, by contrast, rely more on private pensions and tax-advantaged savings accounts such as 401(k)s, with contributions made during their working lives matched by employers. But not all workers have much or any savings — and fewer and fewer have union or company pensions — a point that argues against across-the-board benefit cuts to achieve Social Security’s solvency.

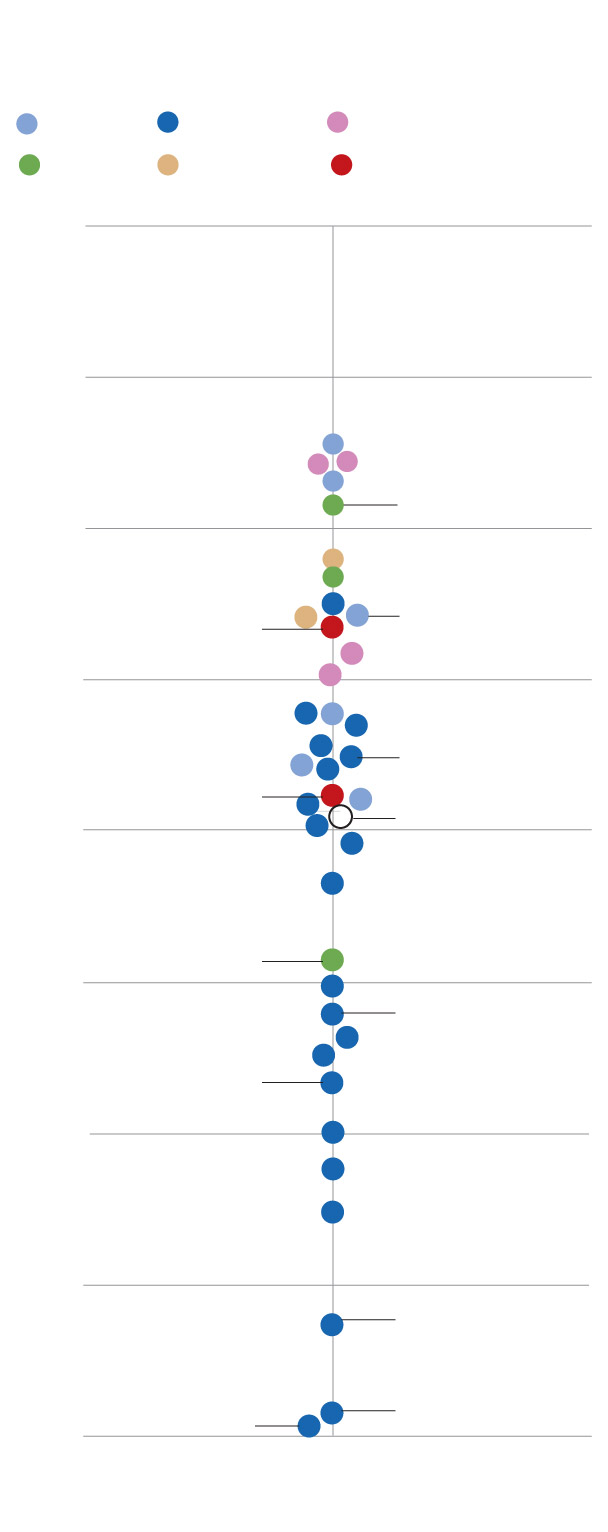

3. As a share of GDP, Social Security spending is about average

Social Security is one of the priciest items in the U.S. federal budget, as are pension systems in many other countries. At 7.5 percent of gross domestic product, the United States spends about the same on Social Security as the OECD average, though much less than some industrialized nations such as France, Greece and Italy.

Percent of GDP spent on public pensions by country

Percent of GDP spent on public pensions by country

Social Security would be substantially reinforced if birth rates went up, leading to a higher ratio of workers to retirees. But fertility trends in the United States, as around the world, have been dropping for years. Nancy Altman, president of the advocacy group Social Security Works, argues that increasing immigration, rather than trying to lift birth rates, would best address this labor-force shortage. “We’re not being nice guys by allowing immigration,” she said. “It’s self-interested. It’s better for our economy.”

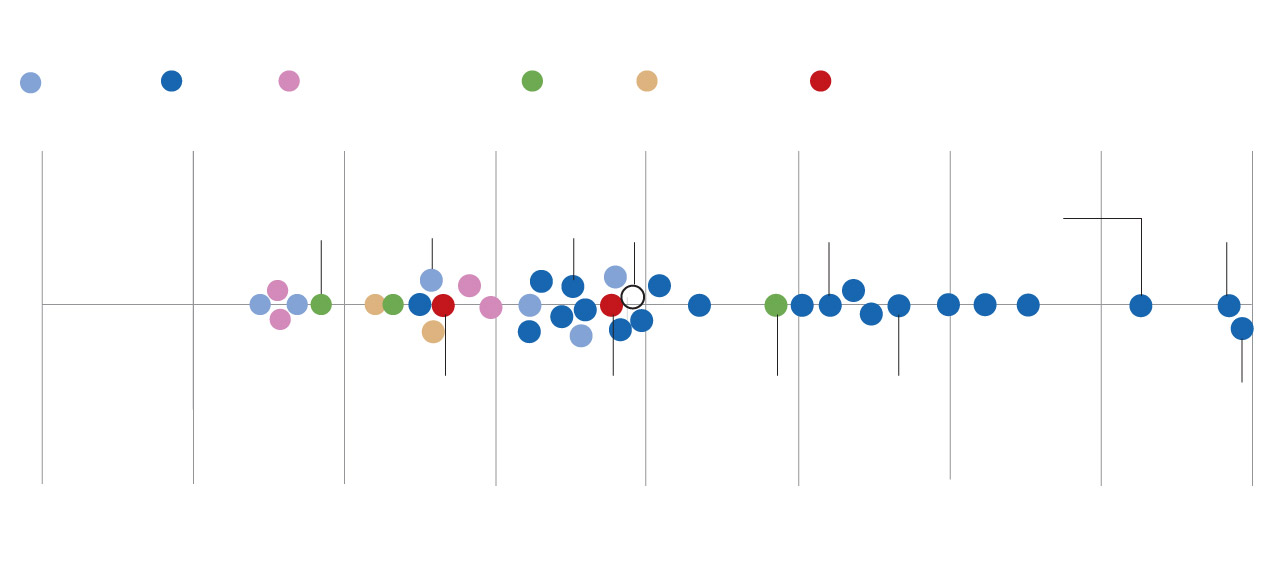

4. Social Security tax rates are lower than in many other countries

Social Security is funded by taxes paid by workers and their employers over the course of their careers. American workers pay 6.2 percent of their wages while their employers pay an additional 6.2 percent, adding up to a total of 12.4 percent. In 113 countries, the total contribution rate is higher than America’s 12.4 percent; the worldwide average is 16.3 percent.

There is great variance both in who pays and how much they pay: Romanian workers, for example, contribute 25 percent of their wages, while their employers usually pay nothing. On the other end, salaried workers in Australia, Lebanon, Russia and Ukraine contribute nothing, while their employers foot the bill.

In the United States, some Democrats have cautiously endorsed the idea of raising tax rates, while conservatives argue that such comparisons are misleading. Social Security is based on progressive allocation — low-wage workers get more back in benefits relative to their salary, while high-wage workers get less back. Higher tax rates are uncommon in countries with similar redistribution, said Andrew Biggs, an American Enterprise Institute researcher who worked on Social Security reform in the George W. Bush administration.

“When the tax rates tend to get high, the benefits tend to get less progressive,” Biggs said. “You can do this high tax rate if you make it less progressive, because people feel like they’re just paying for themselves, not other people.”

While its last calculation is now over a decade old, the OECD has rated how countries compared in redistributing benefits. On a scale ranging from 0 (not at all redistributive) to 100 (the most progressive), the OECD ranked the U.S. system at 42, slightly above the OECD average of 39. That’s more progressive than countries like Finland (4) or Sweden (negative 13, meaning the system is regressive and takes from the poor to give to the rich). In those Scandinavian countries, tax rates are higher, but the relationship between lifetime earnings and retirement benefits is much closer, Biggs pointed out.

On the other hand, some countries that redistribute benefits more tend to have lower tax rates: Canada gets a 92 for progressivity — one of the highest in the world — and has a tax rate of 10 percent.

5. Social Security taxes are capped for the richest Americans

Recent debates over Social Security financing often focus on the threshold at which American workers no longer pay that 6.2 percent tax on their wages, which is currently $168,600 in annual income. Earnings above that cap are not subject to Social Security taxes, which means huge chunks of income are exempt for highly compensated workers. (Benefits are also capped, so Social Security also replaces a smaller share of income for high earners.)

Many Democrats have argued that raising or eliminating the cap would bring in enough money to help shore up Social Security for decades to come. Biden has included modifications to the cap in his budget proposals in office and in his 2024 campaign plans. The idea that has parallels elsewhere: Costa Rica, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Iceland and Portugal are among the nations that do not cap wages subject to retirement taxes.

In countries that do have caps, some exempt more income than others. In Canada, the cap exempts income starting at just 79 percent of the average worker’s salary, meaning even ordinary workers don’t pay taxes on a portion of their income. In countries like Mexico and Colombia, by contrast, the cap doesn’t kick in until a person has earned many times the national average — meaning more highly compensated people pay taxes on more of their income.

The American cap of $168,600 works out to about 2.3 times the average worker’s annual wages, putting the United States close to the median globally.