It was a top-secret location created from the farmlands and pastoral rolling hills of northeast Tennessee in the early 1940s. Even the people who worked and lived there from 1942 to 1949 didn’t know the whole story at the time. It was simply referred to as the Manhattan Project.

What began as Clinton Engineering Works has become the city of Oak Ridge, one of three sites for the Manhattan Project at the beginning of World War II. Its purpose? Atomic research that led to the creation of the atomic bomb.

“In its heyday in 1945, Oak Ridge was the fifth-largest city in the state with more than 75,000 residents,” says Ray Smith, the official city historian of all things Oak Ridge. “Yet until (atomic bombs) Little Boy and Fat Man were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the secret of Oak Ridge was protected. It’s amazing to realize that of all those people, no one there knew what work was being done. Everything was compartmentalized, and people were strictly forbidden from talking about what they were doing.”

About 3,000 families were displaced along Black Oak Ridge as the federal government took over the area in the early 1940s. Contractors constructed large industrial buildings, makeshift houses, dormitories, a nondenominational chapel, guest lodge and community swimming pool.

The 60,000-acre complex in East Tennessee functioned like a city with concrete construction facilities, a cafeteria, a commissary and schools. Underemployed and unemployed people were hired to work on small parts of the project, intentionally kept unawares to protect a national secret.

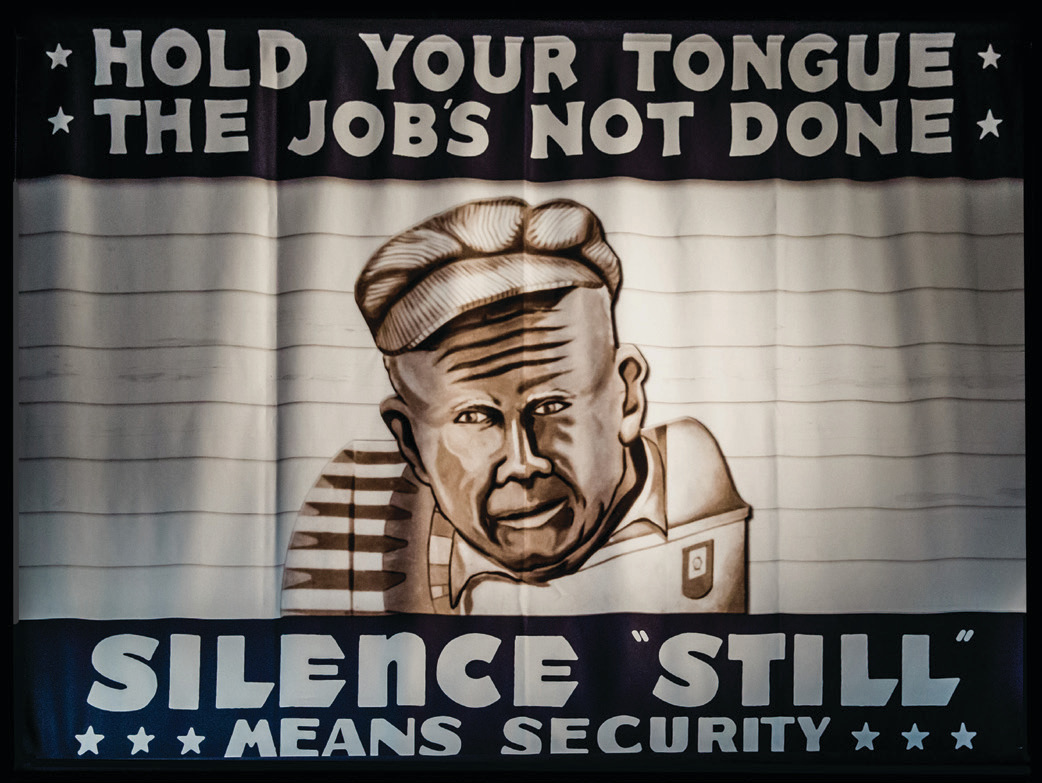

Signs throughout the area warned of the need for secrecy: “Hold Your Tongue. The Job’s Not Done.” “Who Me? Yes You … Keep MUM about this Job.” “Your Pen and Tongue can be Enemy Weapons. Watch What You Write and Say.”

“When workers traveled by bus to nearby Knoxville, they were sometimes met with questions like ‘What are you doing out there?’ to which the reply was ‘As little as possible.’ Even couples working in different areas weren’t allowed to discuss what they did,” Smith says. “Some of the women sat all day at consoles, turning dials; little did they know they were enhancing uranium that would be used for making the atomic bomb.”

Smith moved to Oak Ridge several decades after Little Boy and Fat Man brought an end to World War II. For 47 years, he worked at the Y-12 facility, previously used to produce enriched uranium. Along the way, Smith’s interest in history and photography led him to become an authority on Y-12 and the heritage of Oak Ridge.

At one point, he was asked to make a list of all the buildings at the site, nearly 800 of them. Some 300 were demolished; others were repurposed such as the New Hope Community Center, formerly a gathering place for employees’ dances and bingo and now a museum.

He’s written several books about Oak Ridge, compiled years of newspaper columns for The Oak Ridger and consulted with authors, including Denise Kiernan who authored “The Girls of Atomic City.” He was a producer on a 90-minute documentary “Secret City: The War Years” about Oak Ridge, narrated by actor David Keith, as well as a documentary about Manhattan Project and Department of Energy photographer Ed Westcott.

“My purpose is to keep the heritage and history of Oak Ridge alive for future generations,” Smith says. “So much happened here and is still happening, and there are so many stories to tell.”

The Oak Ridge site is one of three units that make up the Manhattan Project National Historic Park, established on Nov. 10, 2015. The other two are located in Los Alamos, New Mexico, and Hanford, Washington.

“To have the full experience of the Manhattan Project National Historic Park, you have to visit all three locations,” says Mark Watson, Oak Ridge city manager. “You’ll only get one-third of a stamp on your national park passport if you only visit one site because each played a vital part in the Manhattan Project.”

As for Oak Ridge, the city is home to several museums that tell the story of the people and the history of the Manhattan Project: The American Museum of Science and Energy, Oak Ridge History Museum, K-25 History Center and Children’s Museum of Oak Ridge. Exhibitions engage visitors on the past, present and future of Oak Ridge.

“What many people don’t understand is that what happened in Oak Ridge more than 85 years ago as the beginning of the atomic age opened the doors to much more,” says Matt Mullins, marketing director of the American Museum of Science and Energy. “From the technology used in rockets and submarines to identifying isotopes to treat cancer, it was just the beginning of transforming our very world.”

Tours of the museums, a chance to speak with volunteer docents — some of whom worked at the top-secret project — and drive-bys past the remnants of the original complex paint a picture of the past; however, Oak Ridge is a thriving community.

“We are still an active site for research and development with many federally secured facilities,” Mullins says. “However, when people visit Oak Ridge, they are not only seeing a part of history; they are getting a window into the future. It’s an exciting place to be.”