The ocean is a powerful and mysterious place that doesn’t adhere to anthropogenic rules. As a result of the sea’s strength, in combination with human error, the ocean has become haunted by ghosts. These ghosts live in the depths of the ocean and float on the surface, trapping and entangling marine species on a global scale, and threatening the long-term health and habitat of ocean creatures.

“Ghost gear”, also known as abandoned, lost, and discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) makes up roughly 58% of macro marine debris by weight and harms both the environment and the economy. There are many ways fishing gear can end up in marine environments, such as through storm events, gear conflicts, and illegal dumping, which makes ghost gear difficult to address and prevent. Once ghost gear enters the water, it can degrade habitat, entangle species, decrease catches for the industry, cause vessel damage, and pose at-sea safety hazards.

As our global oceans are shared and cross international borders, gear can also be lost on the ocean floor due to issues with other industries. These sources of ghost gear often work simultaneously, increasing the volume of ghost gear in the marine environment and causing detrimental economic and environmental impacts.

How does ghost fishing impact the ocean?

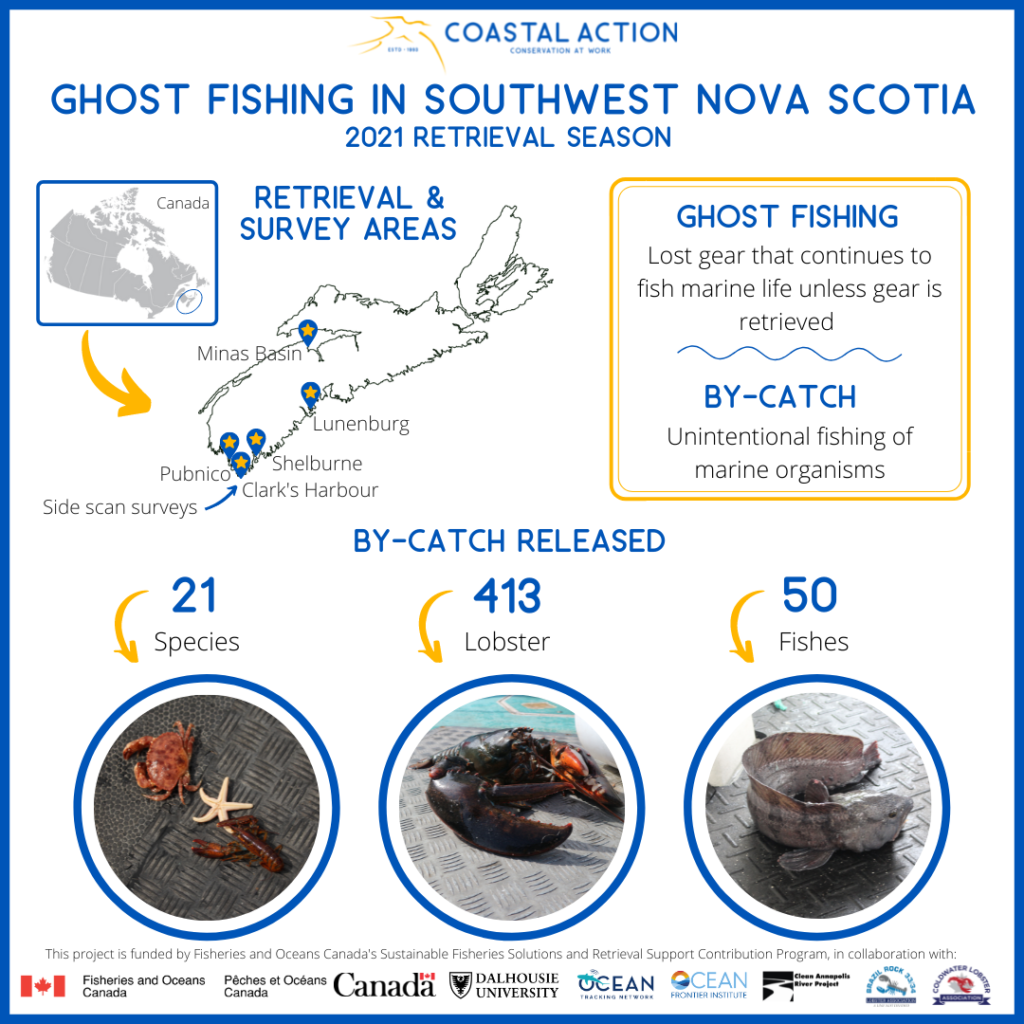

The term ‘ghost fishing’ describes how gear, specifically intact pots or traps, can continue to ‘fish’ ocean species long after the gear has been lost or abandoned, both on the ocean’s surface and on the seafloor. By-catch is the term used to define the species caught indiscriminately through ghost fishing. Ghost fishing can occur when fish and marine species are caught in traps, eventually dying and attracting prey, and inevitably repeating the cycle. As traps and heavier debris fall to the ocean floor it also impacts the benthic marine habitat (on the floor of the ocean). Ocean currents can move and disrupt gear across seafloor habitats, damaging fragile ecosystems. Although there have been arguments made for traps acting as long-term habitat for species, studies show that gear causes more harm, particularly in the first approximately 5 years, by catching and killing species through the ghost fishing cycle. Larger species, such as the North Atlantic Right Whale, are also threatened by the presence of ghost gear in marine environments, most commonly by rope and net entanglements.

Marine life at the end of their rope

In Atlantic Canada, the most common debris found along shorelines are rope, traps, lobster bands, and nets. Rope, used onboard lobster fishing vessels, is commonly made of polypropylene that wears down over time. Once fishers can no longer use rope in their operations, it often ends up in landfills or harbours. The rope that ends up in coastal and marine environments degrades over time and creates microplastic fragments. These plastic particles can then be ingested by marine species, causing physical and chemical impacts over time. There are, however, many efforts from fishers and community members to repurpose this rope for things such as artisan crafts, and most recently, the communities across Atlantic Canada have been working to recycle end-of-life rope.

How does ghost gear affect the fishing industry?

Ghost gear can negatively affect the fishing economy, which has implications for the livelihoods of many communities, and the nation as a whole. This is all the more troubling considering that marine fisheries production and commercial landings were valued as the most profitable sector within Canada’s fishing industry. In Atlantic Canada, the prominent fishing industry is lobster, which contributes significantly to the economic health of the province, to the tune of about $500 million a year.

Ghost(fishing)busters: What’s next in the fight against ghost gear?

Finding lost gear at sea can be like looking for a ghost; the ocean is a vast space and our detection and reporting systems are new and often inconclusive. The fishing industry, including captains, crew, and community members are vital to the success of ghost gear retrieval, remediation, and prevention. They have the know-how to combat pollution from end-of-life gear, locate lost gear, and work on long-term prevention and education strategies within the industry. In Canada, the collaboration from the fishing industry has allowed the successful collection of tonnes of rope across harbours, in addition to their collaboration on at-sea retrieval efforts.

Coastal Action’s ghost gear project has been working collaboratively since 2020 with the lobster fishing industry, researchers, and all levels of government to prevent, reduce, and assess the impacts of ghost gear in Nova Scotia. Collaboration has been the key to success in seeing that ghost gear is retrieved and long-term solutions are created to fix the global issue. In 2021, Coastal Action and fishing industry partners collected 17.5 tonnes of debris, which included 291 lobster traps and 1,750 kg of rope. There were 413 lobsters and 50 fishes released as bycatch. As per the industry’s minimum size requirements, 91 percent of the lobsters released were market-sized, illustrating the economic burden that ghost gear has on the lobster fishing industry.

Protecting the marine environment requires many initiatives working together. Marine Protected Areas are one way to manage ocean and coastal environments and prevent harmful activity from taking place in delineated areas. This can reduce the number of gear conflicts that cause marine debris and ghost gear in offshore environments. Preventing pollution in the first place will also help address the long-term impacts of this pervasive pollutant, though it will require pursuing innovative methods for the lobster fishing industry. Proposed methods include ropeless gear, whale safe gear, and ghost gear detection and tracking. Management practices within the industry and continued collaboration between stakeholders is necessary for prevention. Research and education on the impacts of marine debris, particularly on species at risk, are needed in each region of Canada.

Also important is continuing to find ways to responsibly dispose of end-of-life fishing rope in Atlantic Canada, and across Canada. Access to facilities working on effective end-of-life gear management in Canada has been slow, but initiatives are working to transform rope and debris into building supplies and diesel fuel. These processes help create opportunities for closed-looped systems and prevent end-of-life rope from going to landfills.

Working together to lay ghost gear to rest

It’s evident that no one entity can tackle the complex issue of ghost gear. We need collective collaboration and differing perspectives and to address the issue long-term and on a large scale. As we gain more insight from research, we must make changes in policy and industry. Community-based and regional work is important and should continue to work towards killing’ ghost gear in Canada, once and for all.

References:

- Goodman, A. J., Brillant, S., Walker, T. R., Bailey, M., & Callaghan, C. (2019). A Ghostly Issue: Managing abandoned, lost and discarded lobster fishing gear in the Bay of Fundy in Eastern Canada. Ocean & Coastal Management, 181, 104925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2019.104925

- Goodman, AJ, McIntyre, JA, Smith, A, Fulton, L, Walker, TR, Brown, CJ. 2021. Retrieval of abandoned, lost, and discarded fishing gear in Southwest Nova Scotia, Canada: Preliminary environmental and economic impacts to the commercial lobster industry. Mar Pollut Bull. 171: 112766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112766

- Government of Canada. Ghost Gear Fund, 2022. https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/fisheries-peches/management-gestion/ghostgear-equipementfantome/program-programme/projects-projets-eng.html

- Lively, J. A., & Good, T. P. (2019). Ghost fishing. World Seas: an Environmental Evaluation, 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-805052-1.00010-3

- Napper et al., 2022. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969721052323

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Marine Debris Program, 2015. Impact of “ghost fishing” via derelict fishing gear. https://marinedebris.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/publications-files/Ghostfishing_DFG.pdf

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Environment Directorate, May 2021. Towards G7 Action to Combat Ghost Fishing Gear OECD ENVIRONMENT POLICY PAPER NO. 25. http://www.g7.utoronto.ca/environment/2021-policy-paper-ghost-gear-report.pdf