After graduating from community college in 2018 with an associate’s degree in web development, Alex Najarro wasn’t sure what field he wanted to work in.

He found his answer the next year after he began working as a physical education (PE) instructional assistant at Paradise Elementary School, located within the UNLV campus.

“I ended up in PE and decided I really enjoyed working with kids, and so I wanted to become an educator,” he said.

Najarro was able to get his bachelor’s degree in elementary education within a year at no cost thanks to an apprenticeship program at UNLV under the College of Education’s Nevada Forward Initiative. The initiative includes two apprenticeship programs — the Paraprofessionals Pathway Program (PPP) and the Accelerated Alternative Route to Licensure (A-ARL) program.

UNLV’s programs are just a few of many efforts underway in Nevada to combat persistent teacher shortages, a statewide strategy that also includes pay raises of 18 percent or more and recruiting teachers from outside of the country’s borders.

As of October 2023, the state had nearly 3,000 vacancies among licensed employees, including classroom teachers, according to the most recent data reported to the Nevada Department of Education. That vacancy number has remained stubbornly steady for the past two school years.

“1994 was the last year that the Clark County School District was fully staffed,” said CCSD interim Superintendent Brenda Larsen-Mitchell.

The state’s largest school district started its new school year last month with 1,400 new hires and 94 percent of its nearly 17,000 classroom teacher positions filled. Yet about 1,100 vacancies remain, about the same number it had heading into the 2023-24 school year.

Growing the teacher pipeline

Since its inception in 2021, UNLV’s initiative has added 460 licensed educators to Nevada’s teacher workforce. Those teachers are working in schools across eight school districts including Clark, Washoe and Elko counties as well as in charter schools. Kelsea Claus, the initiative’s associate director of programming and communications, said the PPP and A-ARL programs have a 94 percent completion rate, higher than the graduation rate for teacher prep programs across the Nevada System of Higher Education, which are around 50 percent.

“What we aim to do with this program is to grow from our own existing workforce of folks who have already been serving in various capacities in our schools and communities — in some cases for many years — but have not had a pathway to achieve the degree or licensure necessary to actually be a teacher,” Claus said.

The initiative is also helping diversify the state’s teacher workforce. More than half of the programs’ students are from underrepresented backgrounds. Some are also bilingual, which UNLV officials say is beneficial for the state’s population of 65,000 students learning English as a second language, who are also known as English Language Learners.

The PPP program allows school support staff to earn a bachelor’s degree in one year while continuing to work full-time. The A-ARL program allows individuals with a bachelor’s degree outside of education to earn a master’s degree in that field of study while they work as a teacher. UNLV offers these programs at no cost to students.

In addition, UNLV offers two pre-apprenticeship programs geared toward high school students and individuals who haven’t completed an associate’s degree or the 60 credits of general education courses required for a bachelor’s degree at a Nevada higher education institution.

In September 2023, the Office of the Labor Commissioner’s State Apprenticeship Council approved the initiative as the state’s first teacher training apprenticeship program. The apprenticeship status allows participants to continue working full time at their schools while they complete the programs.

Traditional four-year teacher preparation programs require college students to spend a semester interning at a school. Those positions are often unpaid, which UNLV officials can be a financial barrier for some prospective teachers.

UNLV has been able to provide these programs at little to no cost to participants thanks to various grants from the Nevada Department of Education. CCSD, one of the main benefactors of the teachers who have come out of the programs, allocated about $5 million of its American Rescue Plan (ARP) federal COVID relief funds to the efforts.

“We know the number one school-based variable for student success is the classroom teacher, and so we wanted to invest in people to make sure that every child had a high-quality educator in front of them,” Larsen-Mitchell said.

With the ARP funds sunsetting at the end of the month, Claus said UNLV is actively seeking other funding streams to be able to continue to keep the programs’ cost down for students and reaching out to state and congressional lawmakers for help. Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto (D-NV) has taken interest in the program.

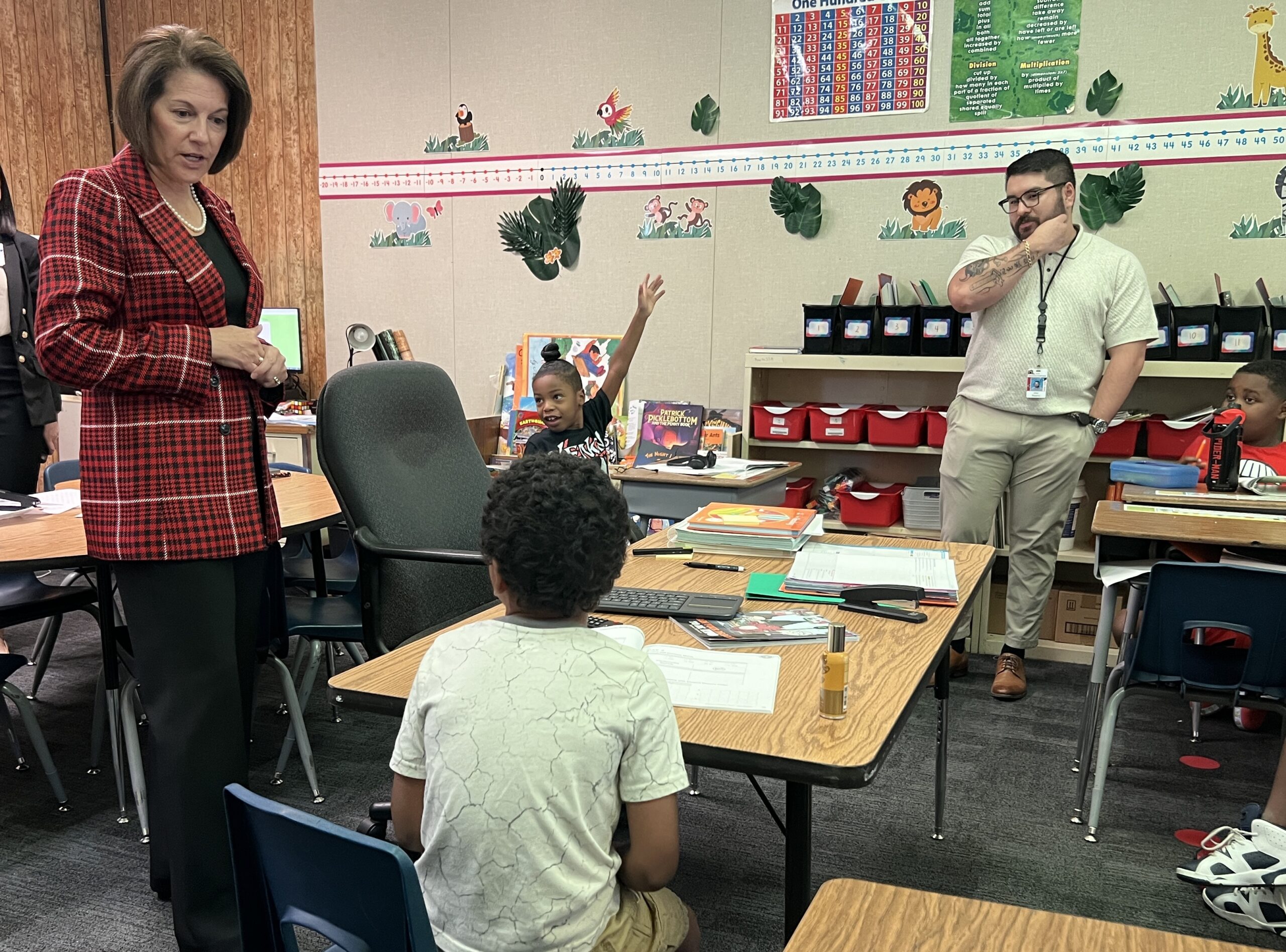

During a Monday visit to Paradise Elementary School, which has attracted seven teachers including Najarro for the programs, she said she’s working on a bill with Sen. John Cornyn (R-TX), the Reaching English Learners Act, that would create a competitive grant program to fund programs that create job training opportunities for future English Language Learner teachers.

“We hope that our legislators will see the results of this program and its impact on the Nevada teacher shortage and prioritize funding to continue this important work,” Claus said. “If we don’t have teachers, we don’t have a workforce.”

Teacher raises

The historic $2 billion increase in K-12 education funding coupled with a $250 million matching fund for teacher salaries have also helped districts across the state raise their pay as a way to attract new teachers.

With this funding, the Nye County School District was able to raise its teacher pay by 22 percent during the past two school years. Though its starting teacher salary, about $51,000 a year, is still less than Clark County’s $55,000, Nye County district officials said the increase has helped it poach veteran teachers from the state’s largest school district, a feat it has never accomplished before.

CCSD’s teacher pay raises, which totaled about 20 percent, tended to favor newer teachers, resulting in some making as much or more than their more experienced counterparts.

“They’re a little disgruntled that pay raises were skewed towards earlier teachers versus later, whereas ours were flat whether you’re a teacher of 28 years or a teacher of two years,” said Nye County School District Superintendent Joe Gent of the veteran teachers leaving Clark to come to Nye.

Gent said another recruitment advantage is that Nye County pays new hires, whether they are from Nevada or not, according to all their years of experience as a teacher. He said other districts limit how many years of experience can be taken into account in a new hire’s pay.

The district´s recruitment efforts paid off, and it started its new school year with only about 30 teacher vacancies, a 50 percent decrease from previous years. The remaining vacancies will be filled mostly by long-term substitute teachers, many who are college students, and three virtual teachers.

“While we deeply appreciate the high quality of long-term substitutes filling our current vacant teaching positions, there are significant instructional advantages when we have full-time teachers,” Gent said. “Over time, we can develop and enhance the instructional expertise of our full-time teaching staff, leading to improved student academic performance.”

Foreign teachers

School districts such as Clark and Mineral counties are casting their recruitment nets wider, bringing in teachers from outside of the country as part of the J-1 visa program that allows professionals such as teachers to come work in the U.S.

The Mineral County School District, located south of Fallon, has been relying on the J-1 visa program for the past four years, Superintendent Stephanie Keuhey told lawmakers during a July interim legislative meeting. A third of the district’s 46 teachers have a J-1 visa. It’s starting this school year with no teacher vacancies thanks in part to the visa program.

“We would not be able to operate if we did not have our teachers from the J-1 process,” she said.

Keuhey said the district is looking to become a sponsor for the H1-B visa program, which, similar to the J-1 visa program, would enable the district to continue to hire foreign teachers. Under the H1-B program, teachers would be allowed to stay in the country for as many as six years, one year more than the J-1 visa. Another advantage is that H1-B visa holders can apply for legal residency while they are in the program.

CCSD has hired 175 teachers through the J-1 visa program for this school year, representing seven countries including the Philippines and Jamaica.

RoAnn Triana, CCSD’s chief human resources officer, said the district is considering becoming a J-1 visa sponsor to attract more teachers by reducing costs for applicants. The district also suggested adjusting the program to allow teachers to come to the U.S. well before the start of the school year so they can receive training prior to the first day of school and reducing the time it takes for them to get a Nevada teaching license.

During the legislative meeting, J-1 visa teachers and Assemblywoman Erica Mosca (D-Las Vegas), a daughter of a Filipino immigrant, said the visa program can cost these foreign educators thousands of dollars.

“Some agencies charge $5,000,” Mosca said. “Some agencies charge $30,000 so what we hear from teachers … they take out a loan from the agency. So by the time they get back to the Philippines, they actually owe more money than they actually made in their five years as teachers.”

During the 2023 legislative session, Mosca and Sen. Edgar Flores (D-Las Vegas) introduced bills, AB308 and SB308, that would have prohibited school districts from hiring foreign teachers from agencies with fees and costs that exceed $5,000. Neither measure received a hearing, Mosca said.

An interim legislative committee is considering supporting legislation similar to the previous two bills, and require schools hiring foreign teachers to develop infrastructure to better support them.