The gloomy global elite strolling the Promenade in Davos this week could cheer themselves up by stopping off for free ice cream courtesy of Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

Or they could drop into the Saudi café for coffee, pumpkin jereesh and a rose mamoul crumble. Then visit Prince Mohammed’s Misk Foundation “Youth majlis” pavilion.

With Russian oligarchs banned, the Saudis stepped into the limelight.

Despite a dire human rights record, the Gulf country wants the world to focus on its economic story: the world’s top oil exporter is one of the few bright spots in an otherwise shaky global economy wracked by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and surging inflation.

Saudi Arabia was the focus of global condemnation after the 2018 brutal murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi and was shunned by many western leaders. MBS, as the crown prince is known, was implicated in the killing, according to US intelligence agencies. He has denied his involvement.

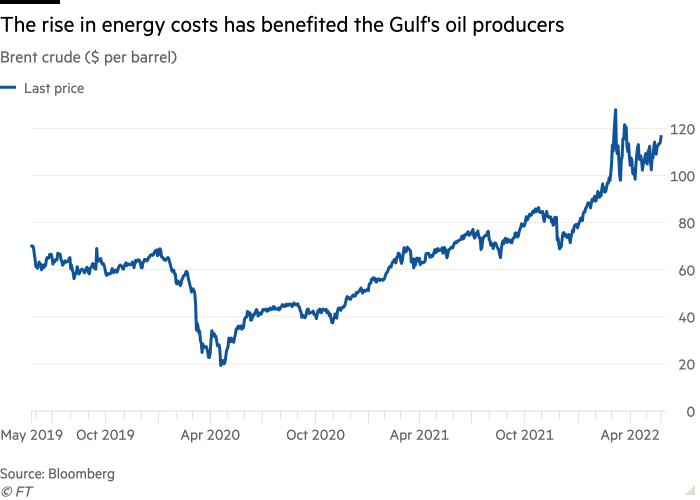

But four years on, Saudi officials are displaying a new confidence. The kingdom and its fellow Gulf energy producers are reaping huge rewards from the turmoil sweeping energy markets, whetting the appetite of bankers and financiers eager to counteract a slowdown in US and European markets.

“This is the most buoyant market we have ever seen in the kingdom. Things were good before we even saw oil prices spike, now it’s just really on fire. And we think it will be for the next five or six years,” said a Gulf-based executive at a multinational that operates in the country.

Flush with cash and emboldened, Saudis hope the energy crisis will change the western campaign against investments in fossil fuels and bolster the kingdom’s standing in the world.

French president Emmanuel Macron visited the kingdom in December and UK prime minister Boris Johnson this year. President Joe Biden remains reluctant to follow suit, but US officials acknowledge a pragmatic need to engage with Riyadh on a range of issues.

While the US and its allies have urged Saudi Arabia to pump more oil to help alleviate market pressures, the kingdom’s leadership argues that the west’s overzealous embrace of green transition had led to years of under-investment and high oil prices.

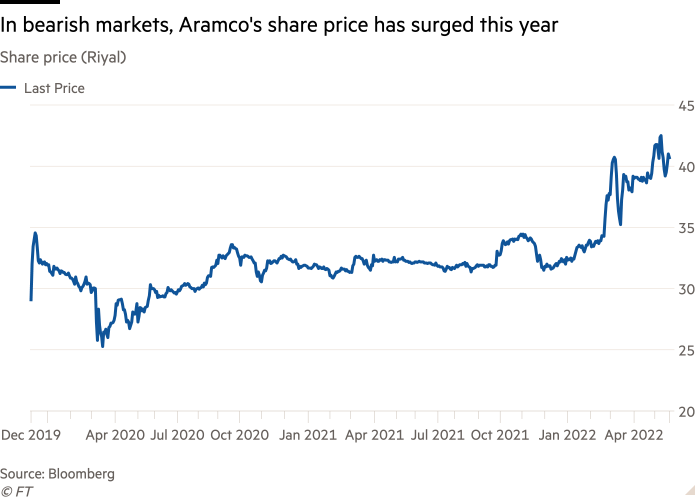

“[The world is] not taking seriously the issue of energy security, affordability and availability,” Amin Nasser, the chief executive of Saudi Aramco, told the FT on the sidelines of the World Economic Forum. The state energy giant recently overtook Apple to become the world’s most valuable company.

Behind the scenes at Davos, delegates from cash-strapped governments around the world were also vying for a slice of sovereign wealth fund investment as petrodollars flow into the Gulf states’ coffers.

Saudi Arabia is already enjoying a windfall from surging energy prices. Its oil revenue in the first quarter was $49bn, up 58 per cent on the same period in 2021. Jadwa Investment, a Riyadh-based bank, forecasts that the kingdom is on course to reap about $250bn in oil revenues this year.

In the United Arab Emirates, visitors have flocked back to Dubai after the coronavirus pandemic. Abu Dhabi, the wealthy capital and the UAE’s main oil producer, is enjoying the rewards of high crude prices too.

“The swing dollar is now in the Gulf. Funds from traditional real estate to technology are now coming to the only place in the world with extra dollars,” said one Dubai-based financier. “It’s a real renaissance.”

Neighbouring Qatar, the world’s top exporter of liquefied natural gas, is benefiting from surging gas prices and this week committed to invest £10bn in the UK over the next five years. The small Gulf state, which is hosting the football World Cup this year, is being courted by governments and energy companies across Europe as the continent seeks to reduce its dependency on Russian gas and oil.

“The Middle East is definitely the strongest region right now,” said Credit Suisse chief executive Thomas Gottstein. “Dubai is just booming, but also Doha and Riyadh offer great opportunities for further investments. There is a huge need for financing for infrastructure, tourism and healthcare as these economies diversify.”

For some bankers, the energy shock brings back memories of the heady days of the petrodollar boom of the 1970s, which followed the 1973 Arab oil embargo, when a Saudi-led coalition of Middle Eastern states cut off supplies to the United States and other countries supporting Israel during its war with Egypt and Syria.

Saudi Arabia has been on a spending spree led by its $620bn sovereign investment fund, PIF, for several years as Riyadh attempts to modernise the conservative nation. It is working on megaprojects, including the ambitious $500bn development of Neom, a vast futuristic city; Qiddiyah, a sports complex on the edge of Riyadh, and a $10bn tourism project on the Red Sea. The PIF has also been one of the most active SWFs on the global stage, investing in everything from blue-chip companies to electric vehicle makers and gaming technology.

With oil revenues soaring the expectation is that the spending will only accelerate. “For the foreseeable future, the Gulf will be the epicentre,” said the Dubai-based financier. “The most interesting deals will be cornerstoned in the region — from the largest buildings in New York to infrastructure and private equity.”

The boom will give MBS significant influence in a world wearied by recession. But the crown prince’s unpredictability means Saudi Arabia could attract the ire of the west again, one veteran financier warned. Western diplomats say that after Khashoggi’s murder — and foreign policy debacles involving Yemen, Canada and Lebanon — MBS has increasingly focused on delivering his economic reform agenda.

However, while he has avoided foreign policy confrontations of late, he still presides over one of the region’s most autocratic and repressive states. That may explain why the Saudis, who have not joined in the western condemnation of Russia, carried another message to Davos: that the sanctions against Moscow — and in particular those against foreign assets at the central bank — set a dangerous precedent. Even as the Saudi delegation enjoyed the attention, there was a wariness that the kingdom too could one day find itself facing the wrath of the west.