Canva

Same fears, new tactics: How efforts to ban ‘bad books’ reached a record high in 2022

Stack of books on a table in a library with one book open in the foreground.

At the start of 2023, in accordance with HB 1467 passed in 2022, Florida schools made national headlines as teachers and librarians covered shelves with tarps and removed books from circulation.

Under the new law, all materials in school libraries and on reading lists must be reviewed by a media specialist who completed a Florida Department of Education training. It also revised the definition of a school library to include personal teacher collections kept in classrooms. As the law took effect, districts took immediate action to comply.

A memo from Manatee County School District instructed schools to “remove or cover all classroom libraries until all materials can be reviewed.” A viral video showed empty shelves at a Jacksonville middle school.

As the purging of Florida’s school libraries caught the nation’s attention, it became the most extreme example of a trend already gaining momentum across the United States: removing books from schools and libraries.

Both the free expression organization PEN America and the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom tracked significant increases in the number of attempts to ban books in 2022. While the scale of these efforts is unprecedented, attempts to censor libraries and school materials have a long and messy history in the U.S.

Stacker looked at banned books data by the American Library Association from the past two decades; combed through historical records, scholarly research, and news reports; and spoke to experts to understand how book challenges have changed over the years.

Shutterstock

Burned or banned: Outlawed books reflect fears and politics of the time

Book burning in orange flames.

As long as there have been books, it seems that there have always been those who oppose them or have corralled them to gain the upper hand. The Chinese emperor Qin Shi Huang ordered a bonfire of books in 213 B.C. to wipe out any comparisons to previous rulers. Livy’s “History of Rome,” finished in 1 A.D., details past rulers who outlawed and burned books to prevent foreign ideas from taking root on Roman soil.

Throughout history, the types of books targeted by challenges often reflect the fears and politics of a particular moment in time. During the Red Scare in the late 1940s and early 1950s, for instance, censorship pressures on libraries became more overt as fears of communism swept the nation and Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s influence grew. Books like John Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath” and even “Robin Hood” came under fire for promoting “un-American” ideas. In 1948, the ALA responded to these pressures by adopting a revised—and more strongly worded—Library Bill of Rights, a document that pledges the commitment of libraries to provide access to information regardless of “partisan or doctrinal disapproval.”

Other moral panics have similarly corresponded with which books are subject to challenges. In the 1970s and ’80s, after the Supreme Court handed down its decision on Roe v. Wade, Judy Blume’s frank discussion of topics including puberty, menstruation, masturbation, and female sexuality in books like “Forever…” and “Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.” made her work a frequent target of bans. In 1982, one year before the founding of the now-discredited drug education program Drug Abuse Resistance Education and amid President Ronald Reagan’s expansion of the war on drugs, “Go Ask Alice,” a young adult book that explicitly details drug use by a teenager, was the most censored book in the U.S. The novel “Bridge to Terabithia” was frequently challenged in the 1980s and ’90s for allusions to witchcraft and the occult as the satanic panic raged across the U.S.

Some books and topics have proven to be evergreen targets of attempted bans, cropping up on most-challenged lists year after year. Books by Black authors, or those dealing explicitly with racism, like Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” and “The Bluest Eye,” Alice Walker’s “The Color Purple,” and Maya Angelou’s “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings,” have been repeatedly challenged on charges of being “anti-white,” for depicting homosexuality, and for themes of sexual abuse. Books with LGBTQ+ characters or storylines, like “Daddy’s Roommate” and “The Picture of Dorian Gray,” have also long been singled out by challengers.

As attempts to remove certain books from libraries and schools intensify, many of the most frequently challenged stories bear a strong resemblance to those targeted in the past. There are, however, key differences in recent book ban efforts—both in terms of scale and who’s behind them.

Emma Rubin // Stacker

2022 set a record for book challenges, almost doubling from 2021

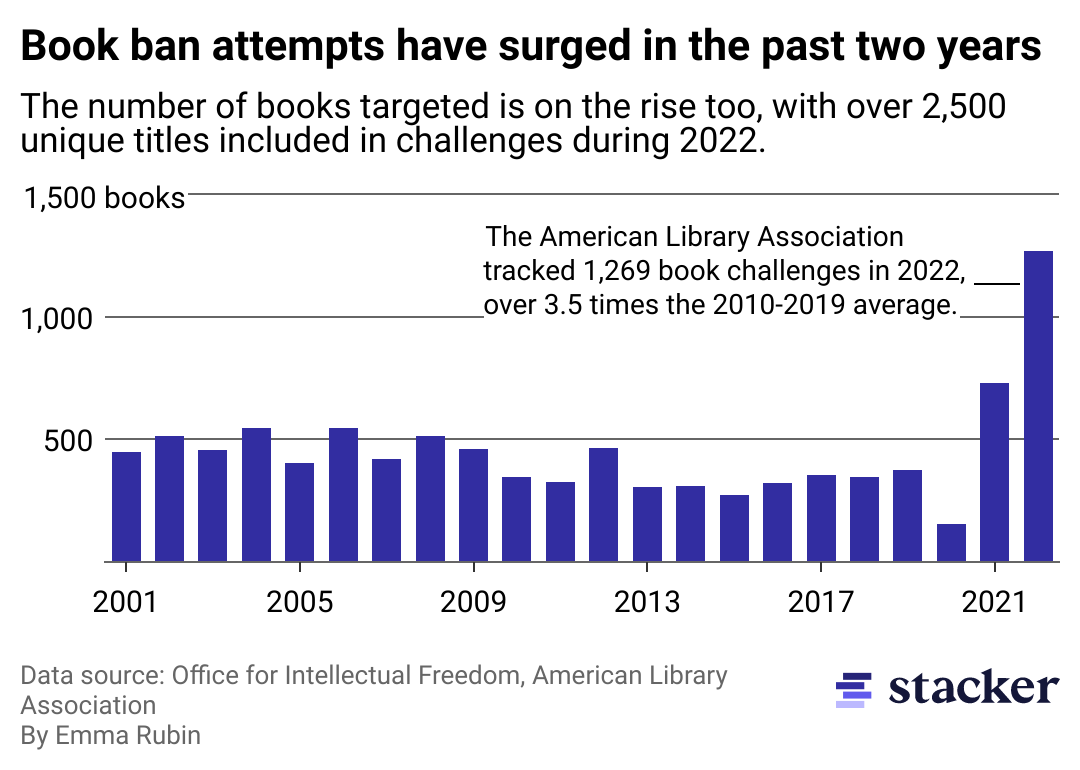

Column chart showing book ban attempts have surged in the past two years. The American Library Association tracked 1,269 book challenges in 2022, over 3.5 times the 2010-2019 average. The number of books targeted is on the rise too, with over 2,500 unique titles included in challenges during 2022.

The ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, established in 1967 to protect people’s right to freely access library materials, tracked a dramatic increase in attempts to remove books from library and school shelves in 2022. The surge in challenges to books is unprecedented in scale—2022 marked the highest number of censorship attempts since the ALA began recording them in 1990. And this number is, in all likelihood, a dramatic undercount, OIF Director Deborah Caldwell-Stone told Stacker.

While last year’s rise in book-banning efforts is unheard-of, it mirrors another recent trend: the uptick in restrictive education laws.

Beginning in 2020 and accelerating in 2021 and 2022, conservative lawmakers in dozens of states proposed legislation limiting what can and cannot be taught in the classroom. Curricula including topics like racism, the legacy of slavery, and LGBTQ+ identities and historical figures have been subject to particular crackdowns. Over 20 laws are currently active in 17 states as of May 19, 2023, according to PEN America’s index of educational gag orders, which is updated monthly.

As educational topics like critical race theory and so-called “gender ideology” have become conservative talking points of lawmakers like Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, the focus of some politicians and parents has increasingly shifted toward restricting books in libraries and schools.

Raising concerns about a book in a public or school library is a well-established process—one that Caldwell-Stone said has its place.

“We actually support the idea that libraries should have a process in place for individuals to raise concerns about materials as part of their First Amendment right to petition government entities, like libraries and schools,” Caldwell-Stone said.

The protocol for challenging a book is fairly simple. Normally, an individual library patron or parent of a student starts by bringing their concerns to a librarian. If discussing the concerns in a conversation does not resolve the issue, the librarian gives the concerned party a form, which asks questions about what parts of the content caused unease and if the patron or parent reviewed the book in its entirety. Once it’s filled out, the form is delivered to the library director, and a committee composed of library staff, community members, or a mix of both will review the material to ensure it aligns with the library’s material selection policy. Reading materials are reviewed based on whether they serve the information needs of members of the community.

Most of the time, according to Caldwell-Stone, book challenges do not result in bans, especially when the official protocol is followed. But increasingly, library patrons and parents are using other, less formal channels to get library materials removed from circulation. Social media smear campaigns and public comment periods in school board meetings have become forums for stirring up controversy about specific books, effectively circumventing established, democratic review processes.

These protocols serve an important purpose, Caldwell-Stone said.

“Formal processes mean taking time to think about the book, to read it, and review the work as a whole rather than focusing on a few paragraphs or an image. [These processes] provide notice to the community, allow other people to speak up against censorship where others might be speaking for censorship,” she said.

Emma Rubin // Stacker

Most of the top challenged 2022 books cited LGBTQ+ and sexual content

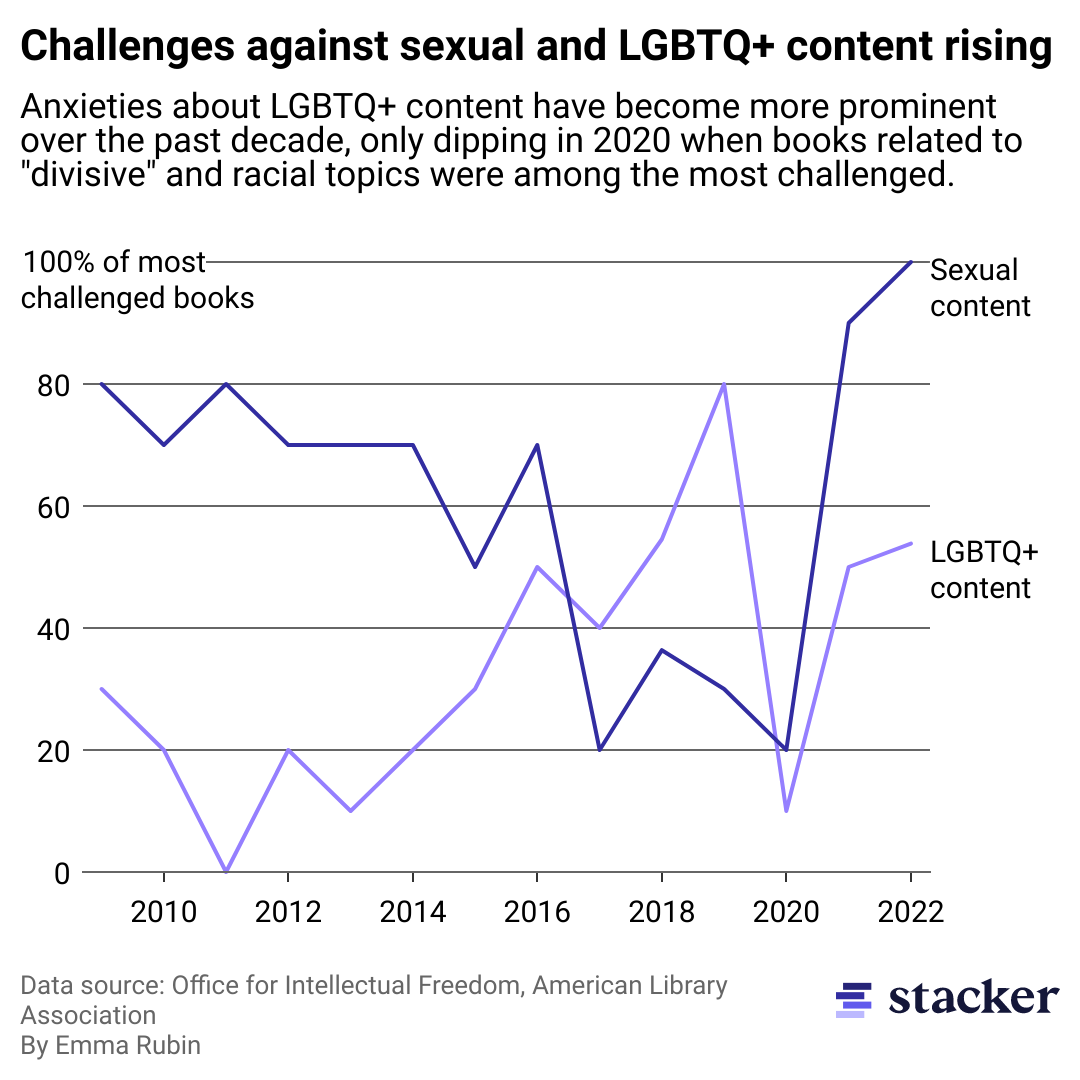

Line chart showing challenges against sexual and LGBTQ+ content are rising. Anxieties about LGBTQ+ content have become more prominent over the past decade, only dipping in 2020 when books related to “divisive” and racial topics were among the most challenged.

Nowhere is the overlap between hot-button politicized issues and the increase in book challenges more evident than in the rise of attempts to ban books containing sexual and LGBTQ+ content. Attempts to censor books with these themes are certainly nothing new—complaints about sexual or “deviant” content date back to the beginning of the ALA’s recordkeeping on book bans.

The increase of challenges on the basis of sexual and LGBTQ+ themes in recent years is hardly surprising considering the corresponding swell of anti-transgender legislation across state legislatures. In 2023 alone, 63 anti-trans bills have been signed into law; an additional 10 have passed and are awaiting a governor’s signature. Many of these laws specifically target gender-affirming health care for trans youth. Meanwhile, 7 out of the top 13 most challenged books of 2022 cited LGBTQ+ content, and all 13 were charged with containing sexually explicit material.

“We’re seeing, overwhelmingly, challenges right now to books that deal with the lives and experiences of groups that have been traditionally marginalized in our society,” Caldwell-Stone said.

Many of the books with the most attempted bans deal with the lived experiences of queer people. In the cases of Maia Kobabe’s “Gender Queer: A Memoir,” Alex Gino’s “Melissa” (formerly published under the title “George”), and George M. Johnson’s “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” which have all topped the lists of most challenged books over the last several years, the authors and their protagonists have been nonbinary or transgender.

Other top challenged books charged with being “sexually explicit” are titles intended to be educational, like “It’s Perfectly Normal,” a book that explains puberty to young people ages 10 and older, and “This Book is Gay,” which offers sex education and coming-out advice for LGBTQ+ teens.

In some cases, the backlash to these books has been much more severe than merely trying to have them removed from library and school shelves. In Heyworth, Illinois, an eighth-grade teacher with 20 years of experience was reported to the police for “child endangerment” after putting “This Book is Gay” out in her classroom, an experience she said made her leave her job. In Jamestown, Michigan, a fight over a public library’s collection, which included LGBTQ+ books like Kobabe’s “Gender Queer,” resulted in the community voting to defund the library. Earlier in the year, the library’s director resigned after being harassed and accused of “indoctrinating children.”

LGBTQ+ content has been a leading reason behind most challenges since 2016, only declining in 2020 when challenges raised regarding “divisive” and racial topics became more prominent. Complaints that year targeted the children’s book “Something Happened in Our Town: A Child’s Story About Racial Injustice” and the young adult nonfiction book “Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You.” Also challenged in 2020 were Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye” and Angie Thomas’ “The Hate U Give,” a young adult novel about police brutality.

Stacker categorized the reasons listed for the top challenged books since 2009 and visualized their prominence over the years.

Emma Rubin // Stacker

School libraries are being targeted more frequently

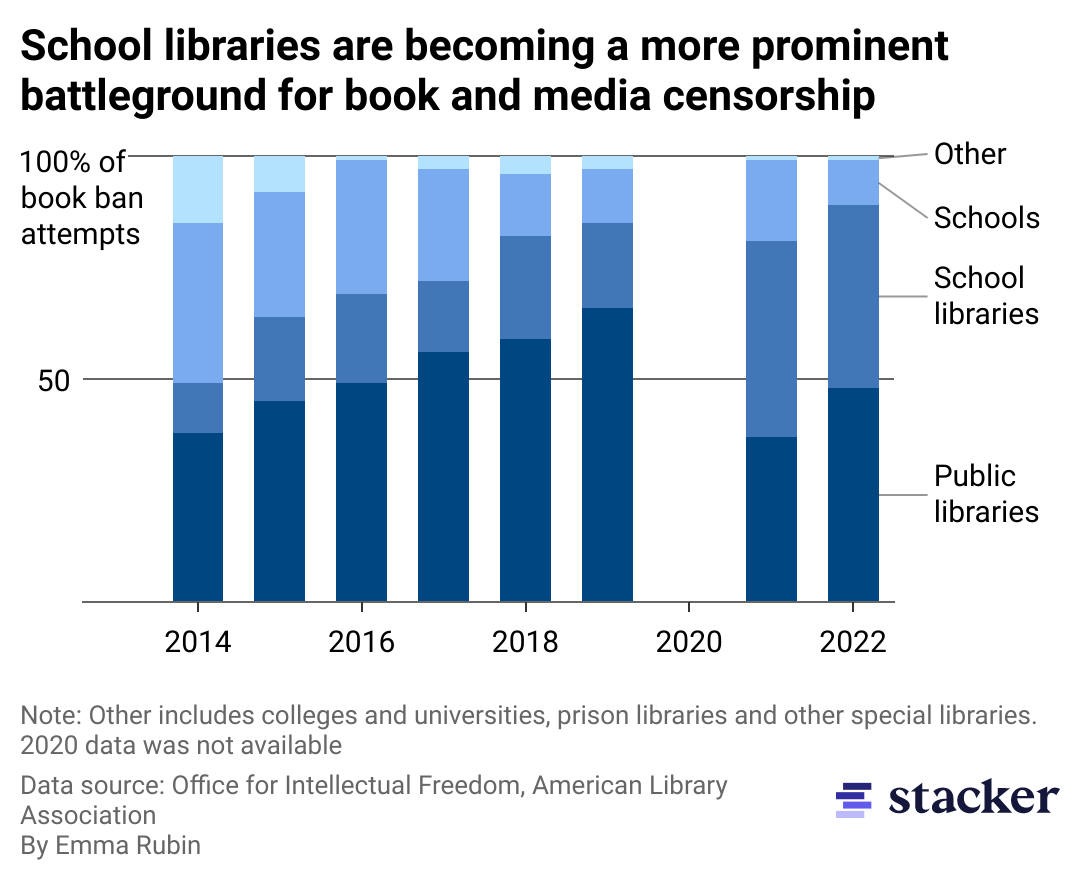

Column chart showing school libraries are becoming a more prominent battleground for book and media censorship. Venues also include schools, other, and public libraries.

As Florida school librarians began reviewing books in compliance with HB 1467, the strictest book legislation in the nation, a new problem presented itself: the project of going through thousands, or millions, of titles takes untold hours of time and staffing—resources few school districts have.

The process of reviewing entire school library collections is a significant undertaking and can require schools to hire additional staff. While state-level data is not available, 2015 national data showed there are 0.68 full-time and 0.21 part-time librarians and library media specialists employed for every school library.

Duval County Public Schools in Jacksonville is one Florida district confronting a high vacancy of media specialists. With a collection of 1.6 million books, 1 in 5 of its 70 positions across 200-plus schools were unfilled, according to reporting from Jacksonville Today. As of May 18, the district has so far reviewed 6.8% of its titles.

In May 2023, PEN America, along with the publisher Penguin Random House, the authors of several banned books, and parents of students, filed a lawsuit against Florida’s Escambia County School District over the school board’s decision to remove several books from its collections. The suit is the first indication that battles over book bans and the constitutional right to information are starting to take place in courtrooms on top of social media and school board meetings.

Only recently have school libraries become common targets for book challenges. Prior to 2021, public libraries and specific challenges against books for school assignments made up the majority.

When public libraries receive challenges, however, they have more flexibility due to the wide range of people they serve. In defending book challenges, public librarians are able to cite the Library Bill of Rights and remind patrons that these resources are provided “for the interest, information, and enlightenment of all people of the community [emphasis Stacker’s].” Librarians may also opt to move books to a more adult-oriented section if mature content is part of the complaint. Schools, however, have no such recourse, and concerns over age-appropriateness can make enforcing standards for collection policies more complicated.

“While we talk about constitutional rights for adults, minors also have rights that are separate from their parents,” Allison Grubbs, the director of southeastern Florida’s Broward County Public Library, told Stacker. “They are their own fully-formed little human beings, and the Constitution, the Supreme Court, [and] the United States government have recognized that they have rights that do not end at the school gate. So where I am most concerned is seeing those rights being eroded due to a lot of fear-mongering.”

Broward County’s library system in the Fort Lauderdale area is joining a growing nationwide movement of creating book sanctuaries in public libraries. According to Grubbs, the library first committed to purchasing additional copies of titles that were being challenged or banned in the local school district and elsewhere in Florida. It’s even gone so far as to issue library cards with the words “I Read Banned Books” printed alongside the county library logo.”

Eleven titles have been banned in the Broward County School District, including “The Bluest Eye” and Khaled Hosseini’s “The Kite Runner,” according to PEN’s index.

Book sanctuaries are a relatively simple setup, featuring displays on shelves or tables of frequently targeted books. “It’s a way where we can bring extra attention to this issue and start conversation amongst our users,” Grubbs said.

So far, Broward County’s book sanctuary, which was set up in April and is the first of its kind in the state of Florida, has gotten largely positive feedback from the community.

“It seems that most of our patrons understand that we serve a diverse community and as a result, we’re going to have a diverse collection,” Grubbs said.

Emma Rubin // Stacker

Organized efforts are accelerating

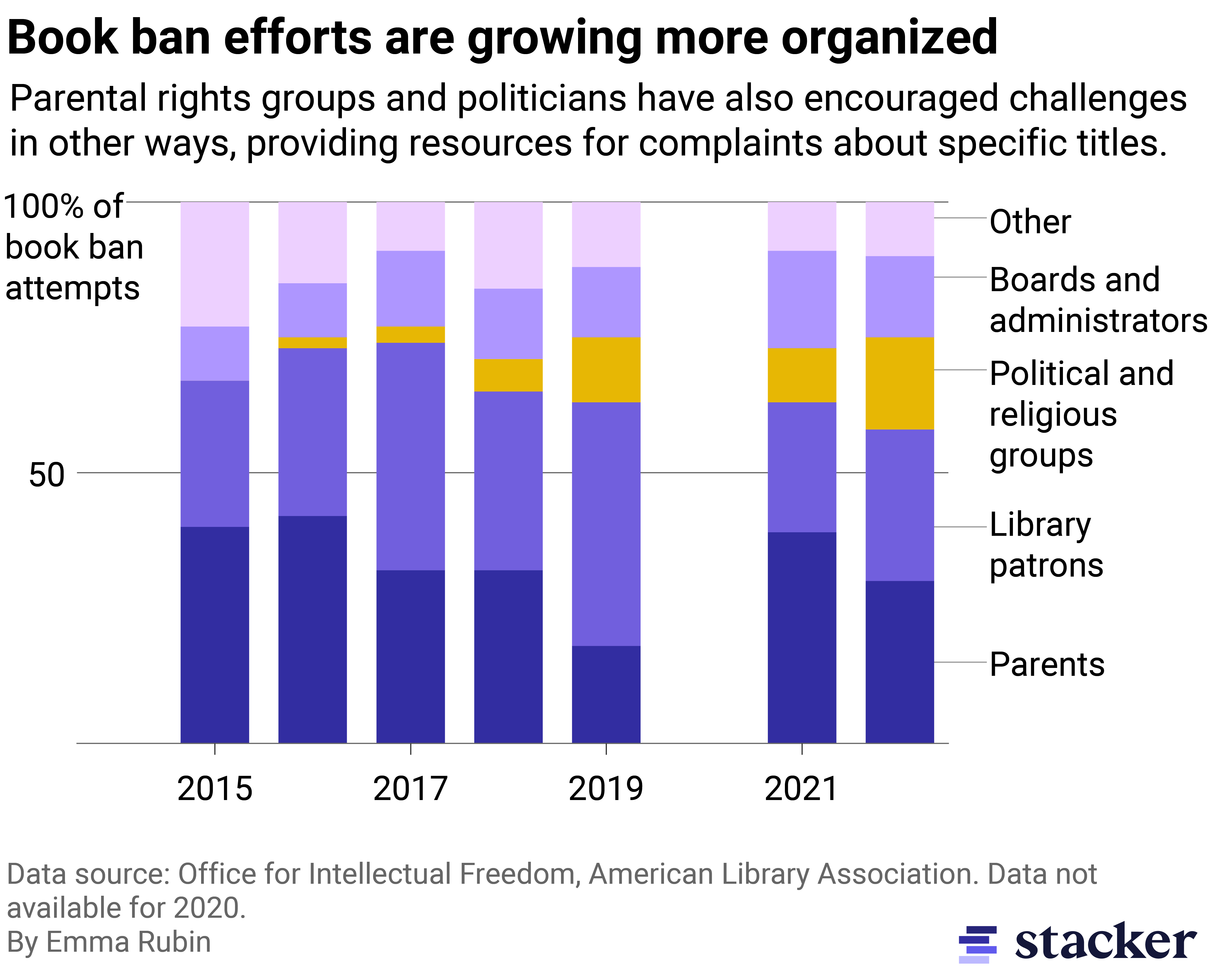

Column chart showing book ban efforts are growing more organized. Groups have also emboldened parents to challenge materials in less direct ways, providing resources for complaints about titles.

Restrictive book legislation is not confined to Florida. In April, the Texas House passed a bill that would ban “sexually explicit” materials from school libraries—a category so vague that librarians and legal experts warn it could be used against books that are age-appropriate but discuss topics like LGBTQ+ issues and identities, sex education, or other subjects frequently targeted by book bans.

These laws mark a definitive shift in library collection decision-making away from librarians and communities and toward lawmakers, political groups, and state governments. But book challenges themselves have also undergone a marked change, namely in who is initiating them—and how.

“It used to be a parent or an individual in the community raising a concern about a book they read, but now we’re seeing, as a result of organized campaigns, efforts to remove books simply because a group says they’re ‘bad books,’” Caldwell-Stone said. “Not because a person has a genuine concern for the content, but because they’re being told from a political or moral standpoint that a group disapproves of books being available to the community.”

Perhaps the biggest player behind the organized book-challenging campaigns is the conservative group Moms for Liberty. Originally based in Florida, the group has expanded its influence by establishing local chapters in most states. It lists its mission as “fighting for the survival of America by unifying, educating, and empowering parents to defend their parental rights at all levels of government.”

Moms for Liberty’s power has been wielded largely through its dissemination of a master document of books that contain “sexually explicit, vulgar, and/or obscene materials.” The list includes an “objective” scale for ranking books’ content, created by Moms for Liberty itself, and is largely populated by books featuring LGBTQ+ stories and characters of color. The ranking tool also includes “book reports,” a database of books containing “objectionable content” that offers specific language for parents or library patrons to use in book challenges while removing the need to read and assess the work as a whole.

The result of these campaigns has been the rise in book ban attempts that include multiple books within a single form. Caldwell-Stone said the Office for Intellectual Freedom has gotten reports of as many as 50 titles within one challenge. The inclusion of multiple books on one form is usually an indication that the concerned party probably hasn’t actually read and assessed the materials—and that it’s likely part of an organized campaign, according to Caldwell-Stone.

“We tend to think that book challenges, they come, and they go,” Grubbs said. “This is unprecedented what we are experiencing now, and it’s really sad to see these adults just really try to silence voices—silence people of color, silence people who are LGBTQ+—who are trying to shape the world in their image. The world is struggling back because that’s not how we live, that’s not who we are.”

Data reporting by Emma Rubin. Story editing by Carren Jao. Copy editing by Paris Close. Photo selection by Abigail Renaud.