It’s been almost a decade since the Austin elementary school my kids attended, the school formerly known as Robert E. Lee Elementary, was the site of an early skirmish in the latest round of American culture wars. From 2015 to 2016, I was in the center of it all, along with my wife and a small group of similarly liberal and left-wing parents who organized to change the school’s name to something less awful.

I’ve been thinking about that experience lately, in part because we’re at a potential inflection point in the broader arc of the culture wars. The more extreme manifestations of the “woke” movement have passed their peak, while the right-wing backlash is at full force, leaving us with something like the inverse of the balance of power that was in play back then. In Texas, for instance, the right is aggressively imposing its cultural views on the broader public—banning diversity, equity, and inclusion programs in higher education; restricting access to certain forms of medical care for transgender youth; banning abortion in almost all circumstances. If my allies and I successfully navigated the shoals of left and right back in the mid-2010s, our efforts may hold some lessons for how to steer a similarly sane course in 2024—in those shrinking spaces where local communities have the liberty to make decisions without interference from greater powers.

I’ve been writing about political ideas for most of my adult life, but except for a brief stint working as the media liaison for a pro-union group during my college days, I’d never come as close as I did during that 2015–16 school year to the actual mechanisms of power and policy. I schmoozed school board members. I spoke at school board meetings. I organized other parents and liaised with the principal. I experienced a bitter schism within my own faction. It was a profound political education, and a lesson in the strength and virtues of liberalism, the toxicity of certain strands of both reactionary conservatism and identity-based leftism, and the potency of rhetoric. It was also a lesson in how to get along with your neighbors—and what to do when you just can’t.

Before that year, a few parents at the school had raised the idea of changing the school name. Ours is a deep blue neighborhood, not far from the University of Texas at Austin campus. We don’t have much of a taste for Lost Cause romanticism, the ideology that was central to the school being named after Lee back in the thirties. The political will to force the issue, however, simply hadn’t been there.

Then on June 17, 2015, Dylann Roof walked into the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, and shot ten Black worshippers. Nine of them died. This was two years or so into the Black Lives Matter movement, but the deaths that catalyzed it—those of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and Trayvon Martin—had focused attention on the criminal justice system, not on the persistence of Confederate memorialization throughout the American South. Roof’s explicitly neo-Confederate ideology altered the equation, bringing the question of Confederate symbolism into the heart of the movement.

In the years since then, hundreds of flags, monuments, and schools have been removed, renamed, or recontextualized. Texas in particular has been aggressive about removing and relocating Confederate symbols. It was clear that there was an opening that hadn’t been there before. (And that, incidentally, may be closing now. One Virginia school district decided in May to revert two schools to Confederate names.)

Robert E. Lee was a particularly divisive figure in these conflicts. He had long been depicted by Southerners as the “good Confederate,” the tortured figure who supposedly disliked slavery but felt compelled by his sense of honor to side with his cohort against the invading North. This narrative had served two purposes, one nefarious and one somewhat defensible.

Nefariously, it obscured and mystified the degree to which the South fought the Civil War to defend the institution of slavery. Semi-defensibly, it helped finesse the reintegration of the North and South after the Civil War; by characterizing Lee as more antislavery than in fact he was, it helped the South very slowly inch closer to national norms on racial equality while pretending it had never been otherwise. Northern scorn for him, in this equation, was therefore regarded as a kind of gratuitous, point-scoring moralism.

At my kids’ school, where the parents were a mix of carpetbaggers like my wife and me (from Connecticut and Massachusetts, respectively) and native Texans, most of us dealt with that complicated historical context by silently erasing “Robert E.” from the school name; we just called it “Lee Elementary” and left it at that. The Charleston shooting instantly made such half-measures insufficient. It was suddenly clear to mostly everyone that the racist ideology at the center of our discussions still had the power to inspire violence. It was clear that the name of the school had to change.

The process began with seven or eight of us, and two things quickly became apparent. We benefited from a major shift in the larger balance of political and cultural forces, and we had a great deal of bureaucratic and political resistance to overcome. According to one administrator I spoke with, many of the teachers at the school were attached to their identities as part of the Lee Elementary community (though not to Robert E. himself). They were worried about change. The principal, who had been in the job a little more than a year, was amenable to renaming the school, but he was getting pressure from angry alumni who wanted its name to stay the same.

The process itself, under the best of circumstances, was going to be a pain in the ass. The Austin Independent School District’s rules for changing school names made clear that it couldn’t be done primarily for political reasons. So those rules would have to be changed, with all the wrangling over legalistic minutiae that such a shift required. Then we’d have to push for a vote to remove the existing name, and then, finally, the school board would vote on what the new name would be. It wasn’t evident at the start where the school board members stood on the issue. One, a Black studies professor at the University of Texas, supported a change, and another vocally opposed it. The rest were conspicuously vague. They would have to be pushed.

We showed up relentlessly—at every school board and PTA meeting, in segments on the local TV news and articles in the local papers, at neighborhood association meetings and on Facebook message boards. And it eventually became clear that we were going to win. The tone of the comments from the school board members shifted in our favor. More and more parents joined our crew. The neighborhood association aligned behind us, as did the Austin newspapers. And the macropolitical winds continued to blow in our direction. Around the country the Confederate dominos slowly toppled, and as each offending state flag was taken down from its statehouse, and each sculpture of a noble Southern soldier on horseback was removed from various courthouse squares, it became easier for us to make our case.

It helped that our opponents weren’t convincing. Most of the commenters who showed up at the school board meetings to voice their support for Robert E. weren’t frothing-at-the-mouth racists. They made thoughtful-seeming arguments about the importance of not revising history in order to bring it in line with contemporary values. But they made them alongside indefensible arguments about Robert E. Lee’s virtues, and their case was often attached to a racism-inflected narrative of the South, perhaps best summed up by the attendee who predicted that “the current anti-Confederate hysteria will pass.”

“He was one of the finest Americans who ever drew a breath,” said one man at a school board meeting. “The hate-mongers of Hyde Park have it all wrong—Robert E. Lee is for all people and all time,” said another. “Robert E. Lee was one of the greatest American this country produced bar none, with the possible exception of George Washington,” declared yet another. “My goodness. If we don’t want our kids to emulate him, who do we want?” If anything, these speakers pushed the center-left Austin school board in our direction.

On August 15, 2016, when the school board voted eight in favor, with one abstention, to remove Robert E. Lee as the namesake of the school, it felt as though our opponents were in part to thank. And then the next, and in many ways more vicious, battle began.

My memory of that year is divided very distinctly into two phases. Phase one was the heartening fight to remove Robert E. Lee’s name, during which I learned something about political organizing, and about politicians, for good and ill. Our cause was just. And we won! And not just a moral victory. We literally changed something. The school has meaningfully diversified over the subsequent years, and though most of that change has been attributable to the principal’s efforts to recruit transfer students, I have little doubt that it made a difference that we no longer repped for Robert E. Lee.

Phase two commenced after Robert E. was gone but we didn’t yet have a name for the new school. At that point, our anti-Robert E. group split in half, with my liberal, pragmatic faction now occupying the right wing of the conflict. To the left of us were those parents who wanted a new name that adequately signaled a commitment to a broader ideology of racial justice.

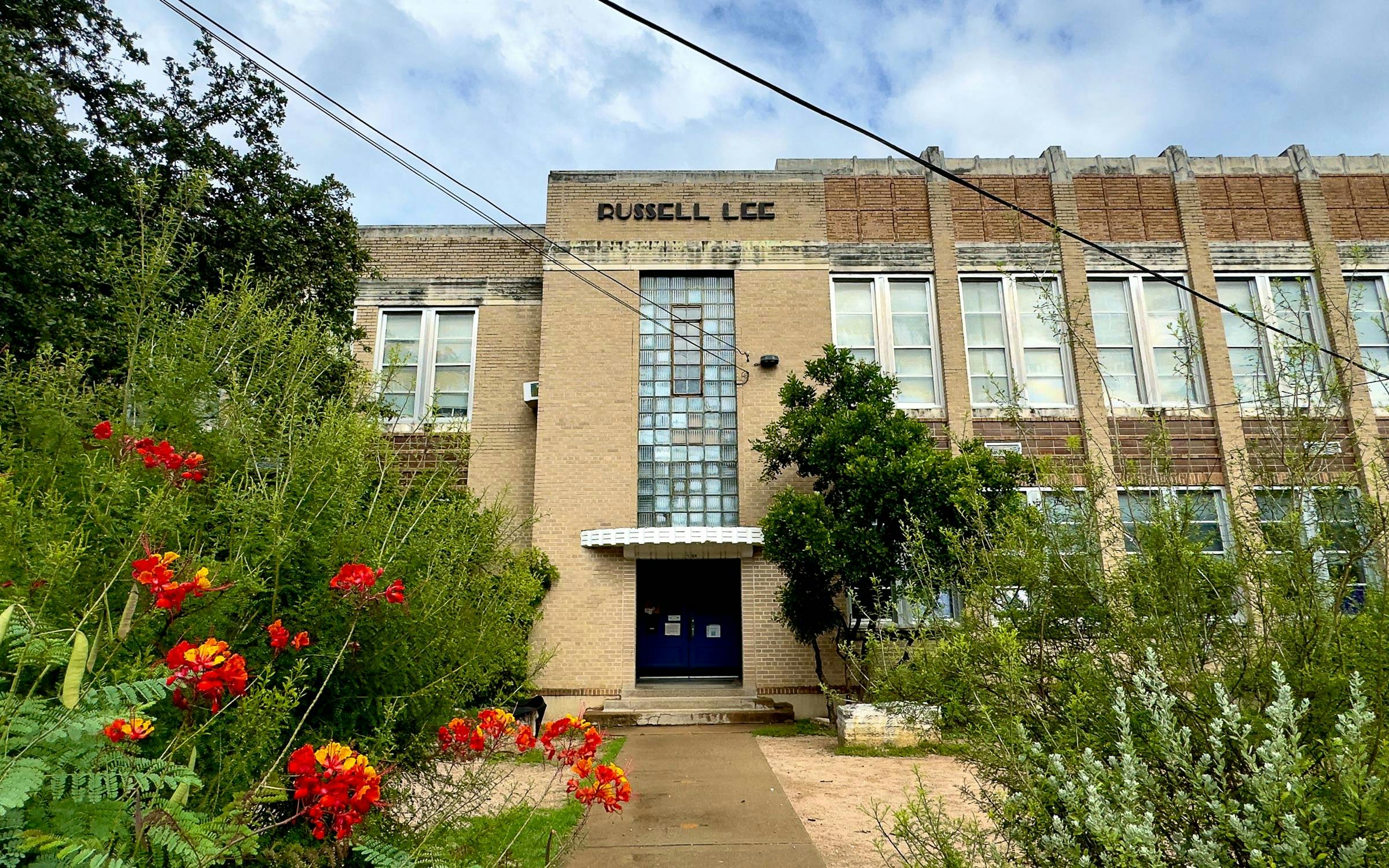

A catalyzing event in the split was the op-ed I wrote for the Austin American-Statesman suggesting that the school should be named after the late Russell Lee, a noted photographer and longtime faculty member at UT who documented the nation’s experience of the Depression and wartime during the middle of the twentieth century and later established himself as one of the great visual documenters of Texas’s many cultures.

“In January of 1940,” I wrote, “less than a year after the school’s founding, The Austin Statesman ran a short piece about the school’s celebration of Robert E. Lee’s birthday. The kids watched a short sketch about Lee’s life. The local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy gave the school a Confederate battle flag. At the end, everyone stood and sang a rousing Confederate song: ‘We are a band of brothers and native to the soil/ Fighting for the property we gained by honest toil.’

“I bet it was exciting for the students. They were being given a resonant history, wrapped in music and imagery and pomp.

I’m not a fan of the version of history they were celebrating. In one sense, though, Lee 1940 got it right. The school name was true to the community’s values, to those things in its history it valued, and to the future it hoped to achieve. I want that kind of name for my kids, too.

“Russell Lee could be that name. It would stand for art and light. It would have an authentic connection to Austin, and to the university where so many of our school’s parents work. In replacing one Lee with another, it would acknowledge the school’s layered past. And it would honor a man who devoted his life to documenting the 20th century in all its beauty and sorrow and complexity.”

This was a pragmatic effort to keep as many people happy as possible. Everyone who wanted to hold on to Lee would get to hold on to Lee. Old school liberals like me, with a bit of a grudge against the Old South, would get the satisfaction of replacing a symbol of the Confederacy with a symbol of the New Deal. And Russell was an artist! Kids love art! Everyone loves art! He even took lots of charming photos of kids!

The only people who weren’t okay with the name were the dozen or so parents in the left faction. Their argument, as I remember it, was that this choice sinned twice over. By holding on to the “Lee,” it appeased the more conservative elements in our community, and by once again naming the school after a white man, it reinscribed the original sin of white supremacy.

As we moved through each of the procedural checkpoints on the path to official name selection (including an open solicitation that went hilariously wrong), the opposition to “Russell Lee” coalesced around three names.

Elisabet Ney was a late nineteenth century sculptor whose home had been turned into a small museum in the neighborhood. Wheeler’s Grove was the original name of a nearby park that had been a post-Civil War site where Black Austinites celebrated Juneteenth. Best of all, members of the left faction made clear, was Bettie Mann, the school’s first Black teacher. Naming the new school after a Black woman, and one who was alive and who had a grandson currently enrolled in the school, would have been the ultimate symbolic justice.

The parent who subsequently became a leading figure of the left opposition was, for a short time, my key ally in spreading the gospel of Russell Lee. She was perhaps the only person other than me who already knew who Russell Lee was. I remember meeting her at a coffee shop once, and she brought a book of Russell Lee’s photographs that she owned; we marveled at how great they’d look on the walls of the school. When she turned against Russell Lee, however, she turned hard.

She first advocated for Wheeler’s Grove, and then went all in for Bettie Mann. By the end of the process, she and I were no longer on speaking terms; during a debate over school closures a few years later, she suggested that our kids’ school should be placed higher on the list of schools that could be shut down. When she left Austin not long afterward, I couldn’t help but wonder whether her anger over the name debate was at least a minor cause.

The split between factions was on display at the school board meeting where Russell Lee was finally approved as a new name for the school. The tally in favor was 8–1, but the most passionate speech of the night came from the lone dissenter, a board member who cast his nay vote as an explicit rejection of the compromise. Bettie Mann Elementary, he said, would have been more “true to our core values of equity, diversity, and inclusion.” As a gesture of comity, the board approved the naming of the school’s kindergarten wing after Mann, who was present at the meeting and was gracious in her acceptance of the lesser honor. The vibe of the meeting, as I remember it, was rather awkward.

Within the school community, the bad blood from the debate persisted over years. Bitter fights erupted over how we would select the Russell Lee photos that we would hang in the school walls; how we would provide Spanish instruction to students; and whether the PTA leadership was guilty of corruption and mismanagement. The sides in these fights, which subsided only after enough kids and parents moved on to middle school, closely mirrored the sides in the fight over the new school name.

Many of us talk rather glibly about white liberal guilt, but I don’t think you can understand any of what happened without some appreciation for the intensity with which many white people experience cognitive dissonance when they consider our country’s attitude toward race. On the one hand is our commitment to basic American principles of equality; on the other is our awareness of the myriad of ways our country has violated those principles when it comes to its treatment of Black people.

As Ralph Ellison once described it, there is an irresolvable gap between the white American’s “sacred democratic belief that all men are created equal and his treatment of every tenth man as though he were not.” Ellison wrote primarily about how white people deal with this cognitive dissonance by denigrating Black people. But the inverse strategy, of loathing white people and fetishizing Black people, makes just as much sense under the same conceptual umbrella. It’s a way that many console themselves, not by resolving the dissonance, but by finding perverse ways to cope with it. The cycle of guilt and expiation needs to be repeated over and over to keep the unease at bay.

Russell Lee’s whiteness and maleness galvanized the left faction. When these factors were introduced to the debate, the tone in meetings changed. Comments on the school’s Facebook group got noticeably more combative. People on opposite sides no longer greeted each other warmly in the halls. It got worse when they eventually coalesced around the plan to name the school after the former teacher. The stakes were no longer just that we were going to honor another white man, but that in doing so we were passing up the opportunity to honor a Black woman.

And there were moments when even I wondered if we were making a mistake. Were we appeasing the local conservatives by substituting one Lee for another? Certainly. Was there something disheartening about replacing one white guy with another, even if the new guy was a friendly liberal with a record of photographing the downtrodden? Yeah, I think so. Was I getting more entrenched in my advocacy for Russell Lee because I was upset about the erstwhile allies of mine who were now attacking me? Most definitely.

What we should have renamed the school was arguable. But the choice wasn’t a stark one between racism and justice, progress and reaction. We’d already won the big moral and political battle. The school was no longer named after a general—the general—of the Confederacy. Now we were just choosing among constructive solutions.

Wheeler’s Grove was poetic and historically evocative, but also rather obscure; in a few years no one would even know or care what it meant. Naming the school after its first Black teacher would have had a kind of cosmic justice to it, but it also carried a faint tinge of tokenism; she was a fine teacher, but no more notable than dozens of others who had worked at the school. Russell Lee was another white guy, but because he’d done so much of his work for the federal government, we would have access to thousands of downloadable photographs to print and frame and hang on the school walls. Perhaps most significantly, because of his surname, Russell Lee was the choice that most effectively reassured those who were hesitant about a change, defanged those who were opposed, and was acceptable to (most of) the rest of us.

It was the best name, in other words, because it won at a moment when winning wasn’t at all assured. The following year, after the politics had tilted even more heavily against Confederate symbols, the Austin school board changed five more school names with only minimal opposition. My older son graduated from Russell Lee to Sarah Lively Middle School, which used to be Zachary Taylor Fulmore Middle School, and it was a nonissue. Few know who Lively was (a beloved Austin teacher who died in 2021), and even fewer know who Zachary Taylor Fulmore was either (a Travis County judge and politician who once served as a private in the Confederate Army).

The lesson isn’t that we should always, or never, reconsider the symbolism of schools, streets, flags, and public parks in light of changes in communal values. It’s that we should be more liberal-minded—not in the partisan sense, but in the older, more temperamental sense that predates the twentieth century. All of us should be open to change. We should be cautious about performative politics replacing substantive politics. We should engage in conversation about how our values are represented in the public square. We should be nuanced.

I’m rather appalled, for instance, by some of the recent decisions to depose and denigrate otherwise admirable historical figures whose racial views were not up to twenty-first century snuff. A culture needs its shared narratives and myths, as well as some humility about what standards are appropriate to judge those from other eras (lest we be judged by our descendants).

When San Francisco’s school board voted in 2021 to rename 44 schools, including George Washington High School and Abraham Lincoln High School, I was just as horrified as the vast majority of San Franciscans, whose outcry was sufficient to force to the board to quickly suspend its plan. Washington and Lincoln were honorable, though imperfect, men whose contributions to the cause of American freedom and democracy were immense.

By contrast, Robert E. Lee sacrificed whatever prior honor he’d accrued on the altar of slavery. The school was named after him because of his commitment to the Confederacy, not despite it. That was the clear motive of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, who were instrumental in advocating that the school be given his name back when the school was opened in the 1930s. They saw an opportunity to advance their racist cause. Just because we shouldn’t change every name of every institution doesn’t mean we shouldn’t change the worst of them. It’s good that we replaced some awful politics and symbolism with better politics and symbolism.

The hard truth is that we’re supposed to be adults, and part of being an adult is accepting that you have to make all sorts of decisions out over the abyss, without clear instructions, dependent only on your insight, experience, values, courage, timing, wisdom, and the vicissitudes of luck to get your decisions right. I think my fellow parents and I in the center-left faction of the intra-left conflict ended up getting it roughly right. I’m happy to take credit for that (in fact one could argue that this whole essay is a victory lap). But we were lucky too, because we stumbled into a moment when national events played into our hands.

We’ve continued to be lucky. When I was making the case for Russell Lee back in 2016, I argued that by naming the school after an artist with a large archive of publicly available images, we’d invite future engagement with his work, which would enrich the school culture and community over time. I only half-believed this, but it was good rhetoric—and I did half believe it! Amazingly, though, this has happened.

Last year photographer Eli Durst, an Austin native and UT Austin faculty member who attended Robert E. Lee Elementary School as a child, published a lovely photo essay in the New York Times about how the school has changed since he was a kid. Earlier this year, the school hosted an exhibition of photos by Russell Lee that were on loan from the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at UT Austin. I recently received an email from a parent who is helping to raise some money to print and frame even more photos for the walls.

Russell Lee himself also seems to be having a bit of a posthumous renaissance. The first biography of him was published in 2021. In March, the National Archives Museum launched a yearlong exhibition of his photography of coal communities, and the University of Texas Press just published a book of photos from that exhibit. The Washington Post ran a lovely meditation on Lee from one of his former photography students; it includes mention of our school, along with some great photos of Russell Lee students looking at Russell Lee photos on the walls. I doubt Lee will ever attain quite the status of fellow FSA photographers such as Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange, but he seems to be moving closer to them, reputation-wise, than any of us had reason to anticipate.

“This is very vindicating,” I said quietly to a fellow parent when I was walking the halls of the school during the recent exhibition. This parent was there with me at the beginning, and, eventually, on my side in the later factional fight. “It is,” he said. He’s actually much more of a lefty than I am, and was initially an advocate of renaming the school Wheeler’s Grove Elementary. After it became clear that Russell Lee was going to prevail, however, he adjusted graciously and worked with the rest of us to implement the name change as smoothly as possible. He accepted that loss as the small loss that it was. He was at the exhibition, as I was, to enjoy and sustain the much greater victory.

As I walked those halls, with all the Lee photographs adorning them, one thing that struck me was the rather astonishing speed with which many of us forget things. I barely even think about Robert E. Lee these days, when I’m dropping off or picking up my eight-year-old son at the school. Most of the parents who were my allies or enemies in those fights have moved on. The principal who steered the school through that storm stepped down a few years ago, perhaps a bit burnt out. It’s just Russell Lee Elementary now, and for most of the students and their parents it must feel as if it always has been. (My kids know the backstory, of course, because their dad can’t shut up about it.)

I hope that Lee’s photography continues to play some role in the life of the school for some time, but even if it doesn’t I don’t think it matters that much. I’m okay with Russell becoming just a name on the front facade. The problem with Robert E. Lee was that he never could quite recede in that way. He was a wound that wouldn’t heal. He was a ghost who haunted us. Russell Lee may or may not have been the name that most optimally atoned for the sins of our Robert E. past, but it sure did exorcise that ghost. And for me, one of the great lessons of my rare foray into politics is that sometimes these kinds of partial victories are enough.

Austin writer Daniel Oppenheimer is the author of Exit Right: The People Who Left the Left and Reshaped the American Century and runs the Substack newsletter and podcast Eminent Americans.