When I was born, in 1946, Lima was home to 640,000 people. Now, as I’m about to turn 77 in the year 2023, Lima is a city of 10 million. The population has grown more than 15-fold. In some ways, you could say that I’ve survived alongside the city. I’ve gotten to know all 43 of its districts and municipalities, and I can say with true pride that I’ve suffered but also delighted in this gray, sleepy city. As Herman Melville describes it, in “Moby Dick”:

Nor is it, altogether, the remembrance of her cathedral-toppling earthquakes; nor the stampedoes of her frantic seas; nor the tearlessness of arid skies that never rain; nor the sight of her wide field of leaning spires, wrenched cope-stones, and crosses all adroop (like canted yards of anchored fleets); and her suburban avenues of house-walls lying over upon each other, as a tossed pack of cards; it is not these things alone which make tearless Lima, the strangest, saddest city thou can’st see. For Lima has taken the white veil; and there is a higher horror in this whiteness of her woe.

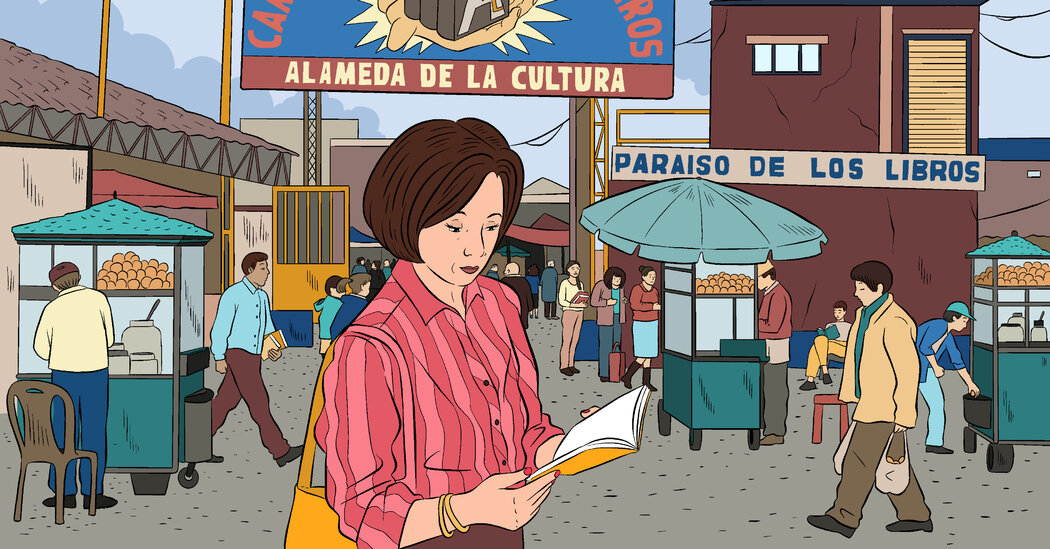

Picture a sandy desert that stretches along the Pacific Ocean. This squalid coastline is bisected by a river, the Rimac. In the middle of the oasis created there is a metropolis — uncertain, cheerful, oh so civilized, somewhat isolated from the world. The luscious tropical flora belies the fact that it doesn’t rain here: The proximity to the sea means that the humid air brings forth new buds and shoots all year round.

Despite, or perhaps because of, their many facets and complexities, Lima and Peru have been depicted and imagined in myriad ways since the city’s official founding by Francisco Pizarro in 1535, and the ensuing five centuries has seen numerous visions, histories and interpretations. I myself have approached Lima from different points of view: I’ve written stories about young people in the margins, in the working-class neighborhoods of Lima, and also, as the son of Japanese parents who settled in Peru, I’ve set Limeñan nikkeis to fiction.

What should I read before I pack my bags?

A number of authors offer valuable insights into Peru’s, and Lima’s, complex past. Let’s start with Inca Garcilaso de la Vega (1539—1616). He was the son of a Spanish captain and a palla — a member of Incan royalty — making him mestizo. He’s considered the first Peruvian, spiritually speaking. His “Royal Commentaries of the Incas and General History of Peru,” about the origins of the Incas, the kings of Peru, and their ways of worship, laws and governance in times of peace and war, was first published in Lisbon in 1609. It was very successful — and is still available now. Today, we know that de la Vega’s vision of the Incas was idealized.

Another essential author in Peruvian letters is Ricardo Palma (1833—1919). His “Peruvian Traditions” consists of four volumes of crónicas, or accounts, of the Incas, the Conquista, the period of the viceroyalty, the struggle for independence and the republican era, all told from his vantage point in Lima. Palma is lighthearted, ironic, amusing and anticlerical by nature, and in his writing he makes fun of the sumptuous interiorities of viceroys and courtesans.