Sinn Féin, a nationalist party committed to taking Northern Ireland out of the UK and into a united Ireland, has secured an historic victory in regional elections but could face an uphill struggle to deliver on its republican dream a century after the island was partitioned.

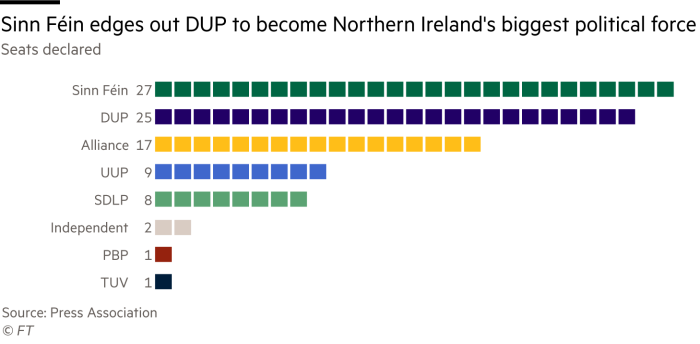

The party long associated with the paramilitary Irish Republican Army won 27 out of the 90 seats in Northern Ireland’s devolved assembly at Stormont, meaning that for the first time a nationalist party has emerged as the largest single group.

The pro-UK and previously dominant Democratic Unionist party secured 25 seats, while the centrist Alliance party, which identifies with neither side in the region’s tribal politics, won 17.

Although Sinn Féin rooted its election campaign on bread-and-butter issues, especially the cost of living crisis, party president Mary Lou McDonald said on Sunday the result should accelerate planning for a so-called border poll — a referendum — on Northern Ireland’s future status, something she wants to see within five years.

“Elections change everything,” she told NewsTalk, a Dublin radio station.

Bill White, managing director of Northern Ireland pollster Lucid Talk, said his surveys showed a rolling average of 50 per cent of the region’s people favouring staying in the UK, 37 per cent backing a united Ireland and 13 per cent being unsure.

“But if there was a border poll, the campaign could change everything . . . [Sinn Féin] are going to push for one,” he added.

Sinn Féin’s victory gives Michelle O’Neill, its leader in Northern Ireland, the right to become first minister in a devolved power-sharing executive involving mainly Catholic nationalists and Protestant unionists, also located at Stormont.

For the first time since Northern Ireland’s creation in 1921, unionists who defend its place as part of the UK have been relegated to runners-up in what James Craig, the region’s first prime minister, once described as a “Protestant parliament for a Protestant people”.

Sinn Féin has been careful not to sound triumphalist, concentrating its focus on getting the executive up and running in the face of the DUP’s threat to boycott it.

Since the 1998 Good Friday Agreement ended the three decades-long Troubles between republicans fighting to end British rule and loyalists battling to remain part of the UK, both communities have shared power to keep the political peace. Despite their titles, the roles of first minister and deputy first minister are identical.

But the DUP says post-Brexit trading arrangements are disrupting commerce between Britain and Northern Ireland and making the region a foreigner in its own country.

The DUP has vowed not to re-enter the executive until the arrangements are scrapped, and without the party’s participation Northern Ireland’s government cannot function in any meaningful way.

UK Northern Ireland secretary Brandon Lewis on Sunday appealed for an executive to be formed quickly by the parties.

But he demanded more flexibility from Brussels on the so-called Northern Ireland protocol that enshrines the region’s trading arrangements, and signalled the UK government was ready to take unilateral action to address the situation if necessary.

Unionists pointed out the DUP, together with the Ulster Unionist party and the Traditional Unionist Voice, actually garnered some 17,000 more votes than nationalist groups in Thursday’s elections.

They increased their vote share to 42 per cent, while the nationalist proportion slipped fractionally to just over 39 per cent.

Sinn Féin secured the same number of seats under Northern Ireland’s proportional voting system as it won at the last elections in 2017, while the DUP dropped three and the Alliance gained nine.

As unionists began a postmortem, the DUP appealed for the three main parties in its community to rally together. “A divided unionism in 2022 cannot win elections,” Jonathan Buckley, a DUP legislator, told the BBC.

“Sinn Féin gets the first minister because the unionist vote is so split but that doesn’t necessarily mean that in the population in Northern Ireland, there is this inevitable surge towards a united Ireland,” said Kevin Cunningham, a lecturer in politics at Technological University Dublin and founder of pollster Ireland Thinks.

His latest survey, published in Ireland’s Sunday Independent, found 51 per cent of respondents in the Republic of Ireland, where Sinn Féin is also the most popular party, believed there should be a referendum — and 57 per cent would vote in favour.

White noted not all nationalists would necessarily vote for a united Ireland nor all unionists to remain in the UK. Indeed, shifting cultural identities — and a weariness with enduring divisions — helped propel the Alliance party into third place in the elections, from fifth in 2017.

A referendum with the potential to splinter the UK would build on Scotland’s drive for independence. Nicola Sturgeon, Scotland’s first minister and leader of the Scottish National party, was quick to congratulate Sinn Féin on a “truly historic result”.

It highlights the risk that British prime minister Boris Johnson is now fighting on two fronts to preserve the UK: in Northern Ireland as well as in Scotland.

But a border poll can only be called in Northern Ireland by the UK secretary of state once it appears likely that a majority in the region would support reunification. A referendum in the Irish Republic would also be needed.

How a united Ireland would work is unclear: many voters in Northern Ireland are attached to free healthcare with the NHS, even though waiting lists for treatment are the worst in the UK, and hate the idea of paying €60 to see a doctor as is the case south of the border.