Frada, Miguel, et al. “The “Cheshire Cat” escape strategy of the coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi in response to viral infection.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences105.41 (2008): 15944-15949. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0807707105

An Invisible World

A drop of sea water contains millions of viral particles. These marine viruses can manipulate the lifecycles of phytoplankton and can thus change the ecology of large parts of the ocean! Since phytoplankton are an important part of the ocean carbon cycle and play an essential role in our rapidly changing climate, it is important that we understand this much overlooked but high impact interaction between viruses and phytoplankton in the future.

Satellite image of a phytoplankton bloom (Emiliania huxleyi) in the English Channel.

Image source : Groom, S. Landsat 7 False Colour Image; NERC EO Data Acquisition and Analysis Service: Plymouth, UK, 1999

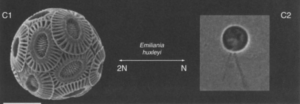

Coccolithophores are single-celled phytoplankton ornamented with calcium disks called coccoliths. One of the most abundant coccolithophores in our oceans, Emiliania huxleyi (Eh), are important for the movement of carbon dioxide between the ocean and the atmosphere.

The Eh lifecycle consists of two phases – 1) a coccolith form, where the cells are non-motile (i.e. at the mercy of ocean currents) and form blooms, 2) a non-coccolith form, with non-mineralized scales as opposed to coccoliths, where the cells have tail-like flagella that allow them to move on their own.

Coccolithophore cells of the species Emiliania huxleyi. C1: coccolith form, C2: non-coccolith form. Image source : de Vargas, Colomban, et al., Academic Press, 2007

Eh are known to form enormous blooms in the ocean, and the termination of these blooms leads to an immense release of their coccoliths. These coccoliths reflect sunlight when detached and this reflection can be seen in satellite images, as seen above.

Bloom termination occurs when the coccolith form cells are killed by marine coccolithoviruses, or EhVs (Emiliania huxleyi viruses). These cells are then replaced by the non-coccolith Eh cells which cannot be infected by the viruses! However, the mechanism for non-coccolith viral resistance has not been determined.

So, are coccolithophores escaping viral infection by switching their entire anatomy to a form that is resistant to viruses?

From the Ocean to the Lab

Researchers performed a 50-day experiment in order to simulate real-time coccolithophore bloom conditions that would occur in the ocean. They found that infected coccolith cells dies out 5 days after infection by EhVs and a new population of non-coccolith cells emerged after 24 days, just as you would expect during bloom termination. These results thus reveal that viral infection leads to the dramatic shift from the first to the second cell form in populations of Eh.

Red Queen vs. Cheshire Cat

In evolutionary biology, the Red Queen hypothesis proposes that two competing species adapt and evolve to outcompete one another – like in an evolutionary arms race. This is a reference to Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass, where the Red Queen (a species) must run (evolve) in order to stay in the same place (persist or go extinct).

This hypothesis does not quite fit the situation here, where the Eh cells are changing forms, not evolving per se. Because of this, researchers dubbed this a new evolutionary tactic, the “Cheshire Cat” strategy, which proposes that the evolution of two competing species (in this case a host and a virus) occurs by reducing host death from viral infection by escaping instead of fighting.

In the case of coccolithophores, coccolith Eh cells escape viral infection by converting to their non-coccolith form which is resistant to EhVs; essentially disappearing as coccolith cells but leaving their non-coccolith form, much like the Cheshire Cat as its body disappears but its grin remains.

I am a PhD student at the University of Chicago and the Marine Biological Lab, currently studying germline development and regeneration in the amphipod crustacean, Parhyale hawaiensis. I did my undergraduate degree in India and did my Masters in Oceanography at the University of Massachusetts (during which I participated in multiple month-long research cruises out in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans!). I am broadly interested in integrating ecology with developmental biology in marine organisms and I hope to comprehend the fundamental interconnectedness of the mysteries that swim in the Earth’s oceans. I am also an illustrator and a PADI certified diver.