From the Puritan town meeting to popularly elected state legislatures to votes for women, Americans have long transformed voting into an anti-corruption tool. During the Gilded Age, good governance reformers doubled down on this strategy by amending a trio of direct democracy tools into state constitutions. The initiative, referendum and recall were all responses to party machines fraudulently increasing their own power to advantage special interests.

Reformers argued empowering the American people through direct democracy would counterbalance the influence of robber barons and party bosses. Nevada joined this movement by not only making the right to propose ballot questions constitutionally protected, but also the right to vote on ballot questions.

Unfortunately, over time, our direct democracy rights have eroded because of restrictive laws, constitutional changes and lawsuits. A recent Nevada Supreme Court ruling is particularly troubling as it may become a nail in the coffin of our right to run and vote on constitutional amendments.

Currently, Nevadans running a ballot question must first muster funding to hire an attorney well-versed in writing the language according to our state’s rules. This provides protection against lethal lawsuits because after submitting a ballot question to the secretary of state’s office, any Nevadan can file a legal challenge to halt the process.

Establishment forces particularly like to weaponize this legal strategy to stop ballot questions that threaten their power, using the courts to strip Nevadans of the right to even gather signatures. These special interests have deep-pockets, such as the Elias Law Firm out of Washington, D.C., which often sues to stop ballot questions in Nevada.

The most common legal challenge is a complaint that a ballot question’s description of effect is misleading because the description of effect can only be 200 words regardless of the initiative’s complexity. This was the case when the Fair Maps PAC independent redistricting commission ballot initiative was first proposed in 2019. Fortunately, this type of legal challenge can be overcome by allowing the plaintiff to revise the description.

The other two challenges can quickly become fatal, however, especially when they overlap.

The second type of legal challenge is an accusation of a violation of the single-subject rule. Ballot Question 3, which will implement open primaries with ranked choice voting in the general election, was challenged under the single-subject rule with the plaintiff arguing changes to the primary were functionally separate from changes in the general election.

Under the single-subject rule, all parts of a ballot question must share a functional connection to avoid tricking voters into voting for something unrelated to the question’s main feature. Often the solution is to remove the part of the ballot language that creates the violation, yet removing part of the language may take away too much of the question’s purpose. But in the ballot Question 3 ruling, Helton v. Nevada Voters First, the Nevada Supreme Court found that the petition did not violate the single subject rule.

Now, because of a 2022 court ruling, there is a third more insurmountable type of legal challenge. Before 2022, if a ballot question proposed a new law or amended a current law and created a new governing entity or function, the ballot language had to identify a source of funding for the new entity or function. This rule did not apply to constitutional amendments because the Constitution mandates compliance.

But, in 2022, the Education Freedom PAC filed a ballot question to amend the Nevada Constitution to create a new school voucher program. Opponents sued and the case landed in the Nevada Supreme Court. In the case’s ruling, the justices changed their interpretation of the Nevada Constitution and ruled that if either a statutory or constitutional amendment ballot question created a new governing entity or function, both types of questions required a funding source.

Currently, there are no taxes in Nevada’s Constitution to pay for governing entities or functions, so it is unclear how our Legislature would handle adjusting a tax enshrined in our Constitution. At minimum, it would take five years to amend Nevada’s Constitution to increase or decrease constitutional taxes.

Further, if a constitutional amendment ballot question included using revenue from an existing tax to pay for a new entity or function, it is likely that someone would file a complaint arguing that the ballot question violates the single-subject rule by asking two separate questions. This is one reason why constitutional ballot questions have not included a method of taxation up to now.

Similarly, if another ballot question or law repealed that tax, does the constitutional entity or function being funded by that tax also cease to exist as well?

If these types of questions are left unaddressed, this new court ruling could severely limit citizen-initiated constitutional amendment ballot questions. This would ultimately translate into losing a tool that has worked for over 100 years to check institutional power.

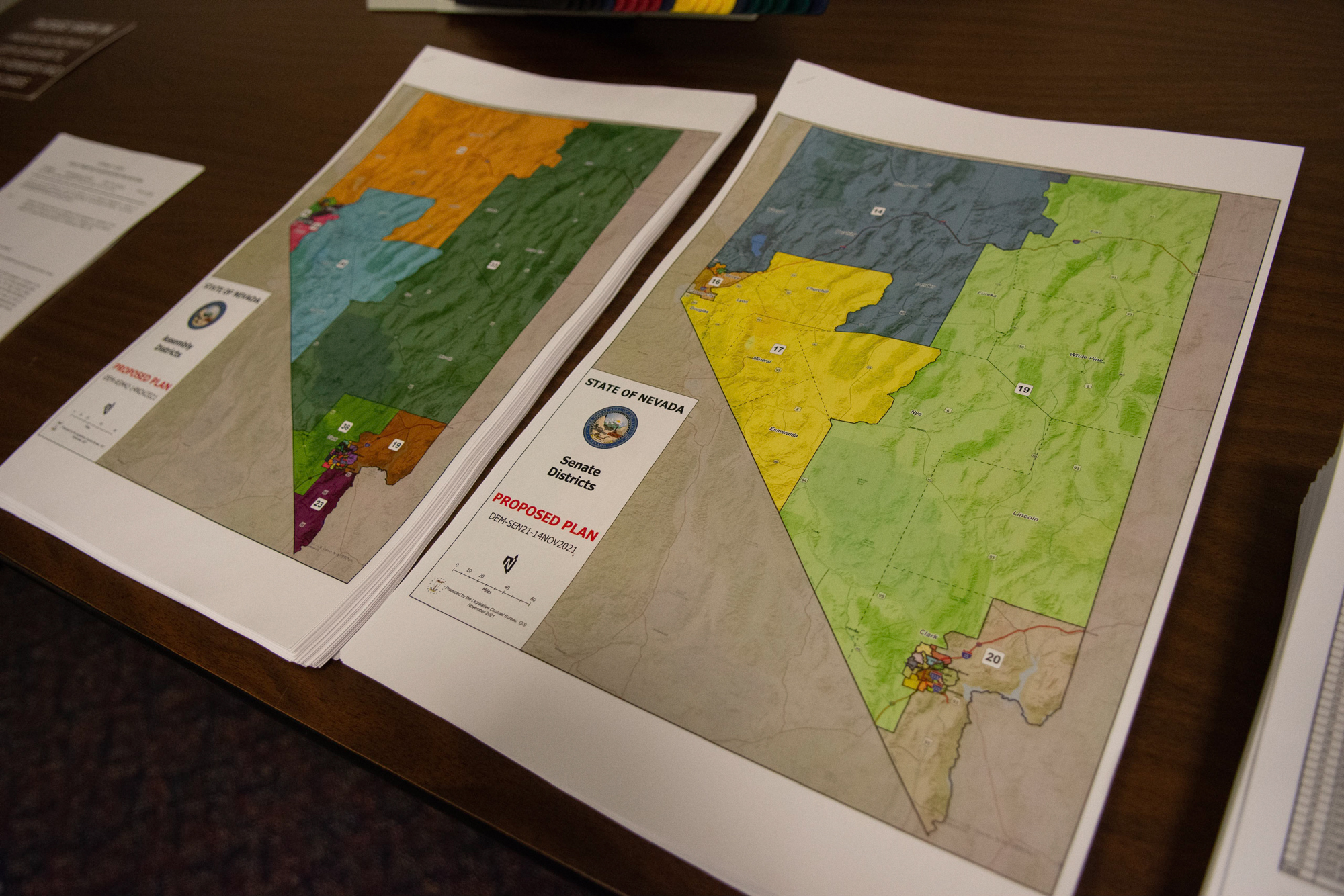

A current example of the problems produced by the 2022 education voucher ruling is the Fair Maps Nevada PAC ballot questions to create an independent redistricting commission. The two ballot questions are identical except one would create an independent redistricting commission to redraw the state’s legislative district maps in 2026, while the second would create the same independent redistricting commission to redraw the state’s legislative district maps during the established 2031 redistricting cycle.

Fair Maps Nevada assumed the district court would reject the ballot question to redraw the maps in 2026 outside of the usual redistricting cycle, which would allow Fair Maps to appeal to the Nevada Supreme Court to request a clarification of the 2022 ruling. Since redistricting is mandated through the Nevada Constitution to take place the year after the decennial census, The second ballot question would be cleared to move forward because it merely replaces the currently funded redistricting entity, the Legislature, with a smaller commission.

Amplifying our worries over the 2022 new court interpretation, a district court judge ruled that both ballot questions would need to identify a new funding source despite funds already existing for the 2031 post-census redistricting process. If the Nevada Supreme Court sides with the district court judge’s ruling on both questions, from this point forward it will be possible to block any constitutional amendment that replaces a currently funded entity or function with an equivalent entity or function by simply claiming unfunded mandate.

Sondra Cosgrove is a history professor at the College of Southern Nevada and chair of Fair Maps Nevada.

The Nevada Independent welcomes informed, cogent rebuttals to opinion pieces such as this. Send them to [email protected].