Jan. 5, 1939

Pauli Murray applied to the University of North Carolina law school, sparking white outrage across the state.

“The days immediately following the first press stories were anxious ones for me,” she recalled. “I had touched the raw nerve of white supremacy in the South.”

A year later, she was jailed twice in Virginia for refusing to give her seat on a Greyhound bus. She graduated first in her class at Howard University School of Law, but Harvard University wouldn’t accept her because of her gender. (Harvard didn’t admit women until 1950.) Instead, she became the first Black student to receive Yale Law School’s most advanced degree.

In 1942, she helped George Houser, James Farmer and Bayard Rustin form the Congress of Racial Equality, known as CORE. Four years later, she became a deputy attorney general in California. Thurgood Marshall described her 1951 book, “States’ Laws on Race and Color,” as the “bible” for civil rights lawyers.

A year later, she lost her post at Cornell University because of McCarthyism. She left her law career to work on her writing at MacDowell Colony, a haven for artists and writers in New Hampshire, where she worked on her first memoir alongside James Baldwin.

“Writing is my catharsis,” she said in an interview. “It saved my sanity. But you cannot sustain anger for years and years. It will kill you.”

She researched her ancestry. “If you call me Black, it’s ridiculous physiologically, isn’t it? I’m probably 5/8 white, 2/8 Negro — repeat American Negro — and 1/8 American Indian,” she said. “I began years before Alex Haley did. I’m always ahead of my time.”

She also penned a book of poems, “Dark Testament,” writing the words, “Hope is a song in a weary throat.”

During her time as a professor in Ghana in the early 1960s, she began to accept that ancestry, she said.

“The difficulty is coming to terms with a mixed ancestry in a racist culture,” she said.

She said she didn’t consider her experience unique.

“I don’t believe that, ‘You came over in chains so how can you feel American?’ That’s poppycock. Thousands are just like me. In fact I probably feel more American than many whites. I just want this country to live up to its billing.”

After returning from Africa, President Kennedy appointed her to his Committee on Civil and Political Rights. She worked with Martin Luther King Jr. and other top civil rights leaders and took part in the 1963 March on Washington. But she remained critical of “the blatant disparity between the major role which (Black) women have played and are playing in the crucial grass-roots levels of our struggle and the minor role of leadership they have been assigned in the national policy-making decisions.”

She helped found the National Organization of Women. In 1977, she became the first Black woman to serve as an Episcopal priest.

“Being a priest is the hardest thing I’ve ever done,” she said. “The first 48 hours were the most difficult of my life. I found myself on the receiving end of tremendous human problems I didn’t know how to handle.”

She rejected the idea that she should slow down. “We shouldn’t stop growing ‘til our last breath,” she said. She died eight years later, and in 2012, the Episcopal church named her as a saint.

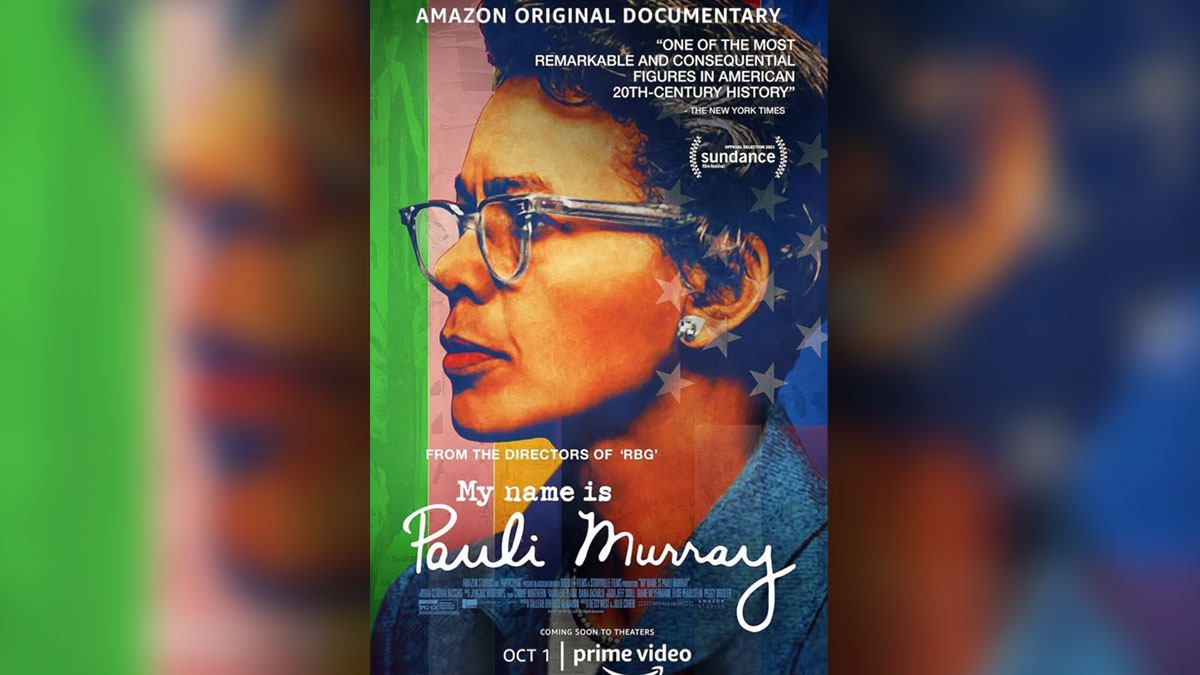

In 2021, a documentary on Murray was released, using her own voice and words as narration. The documentary also includes an interview with law professor Anita Hill.

Even though Murray knew that the odds were often against her success, she kept fighting for what she believed was right,” Hill said. “It takes a lot of courage to be hopeful.”