[ad_1]

Over a recent weekend in Two Harbors, a little town on Catalina Island’s remote northern shores, I donned a wetsuit, strapped on some fins and set off in a kayak to explore the pristine coves around the island.

Gliding through the frigid waters, I marveled at how the light filtered down through the healthy forests of giant kelp — a humongous species of brown algae — and the electric orange Garibaldi fish flitted among the oversized greenery.

If you can withstand the frigid water, it’s pretty unbelievable to swim with kelp. But lately, people have been coming up with all kinds of other ideas about what the miracle seaweed might be good for. For example, feeding millions of people, fueling jet planes and sucking up enough carbon to stave off the worst effects of climate change.

But how feasible is all of this, really? No one knows yet.

This kelp was ready for its close-up.

Courtesy of USC Wrigley InstituteAs I return to the surface after a deep dive into a shimmering kelp forest, I lift up my mask and gaze at one of the world’s cutting edge kelp research field stations, USC Wrigley Marine Science Center, which also happens to front a lovely snorkel spot.

It was here that the world’s first “kelp elevator” was invented and recently demonstrated that the incredibly useful algae can flourish when grown at varying depths. I wanted very much to learn more about this, so I tracked down Andy Navarrete, a postdoctoral researcher who worked on the elevator project.

Navarrete grew up in Berkeley and developed a childhood obsession with the ocean when his parents took him to the local marina. He studied marine science at UCLA and completed a PhD in developmental biology, which at times felt rarified and without practical applications.

“I wanted to do something that would have more impact,” he says, and helping pave the way for kelp to save the planet checked that box.

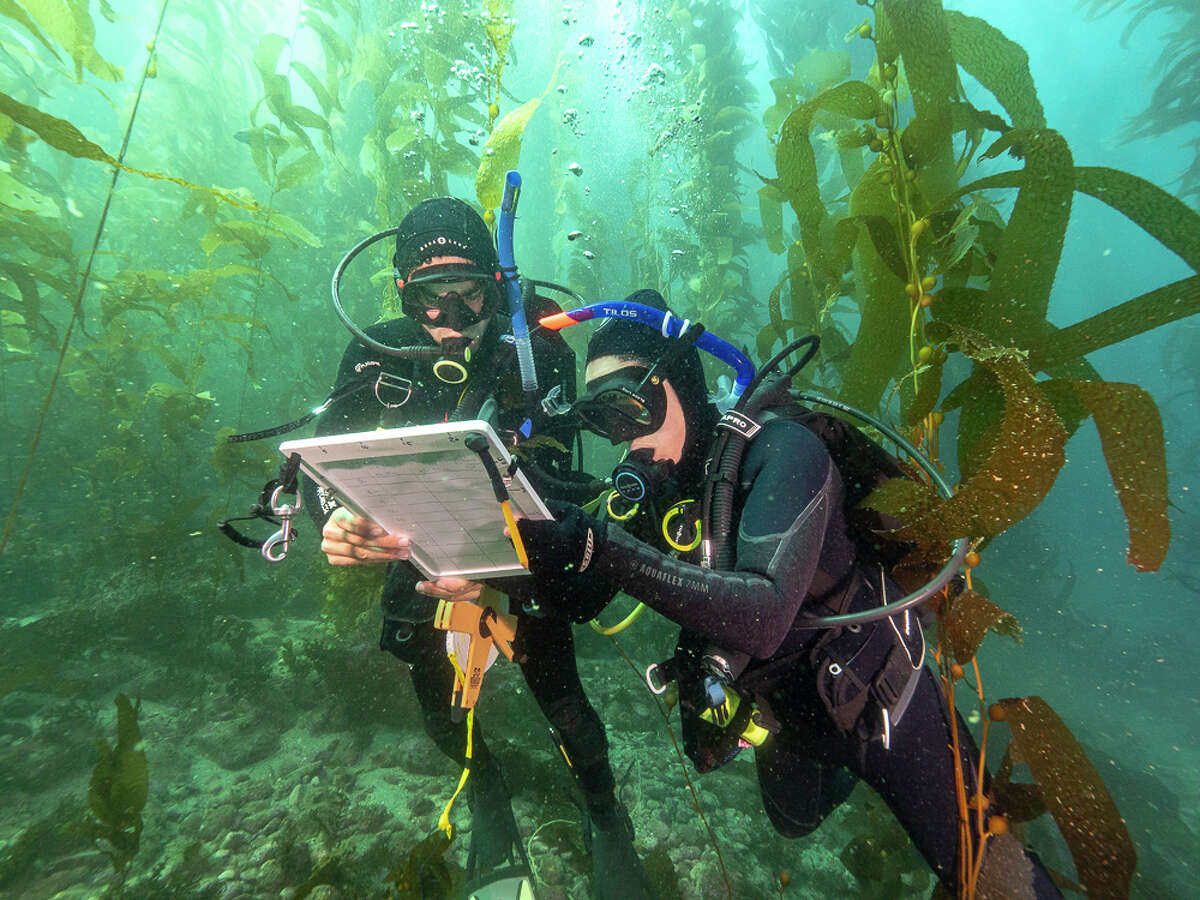

Off Catalina Island’s Parsons Landing, senior scientist Diane Kim and postdoctoral researcher Andy Navarrete study a kelp bed.

Courtesy of Maurice Roper/USC Wrigley InstituteNavarrete cold-called a woman working on the kelp elevator project, and a few months later, he was part of the team, working in partnership with Marine BioEnergy, an open-ocean kelp farm technology company, and later, USC’s Nuzhdin Lab. Funding came from the U.S. Department of Energy’s MARINER program to develop seaweed cultivation for biofuels and bioproducts.

For those who haven’t heard about why kelp is the future, here’s the deal: As climate change does its worst, freshwater and arable land are going to be increasingly difficult to come by. The Earth will still have its vast oceans, though, where kelp could presumably be grown at industrial scale, providing food and an eco-friendly alternative to crude oil, along with significant carbon-storage capabilities.

Kelp grows extremely fast — faster than bamboo, even. And while California’s kelp forests have been hit hard by drastic ocean warming and overabundant urchins in the region, kelp farms wouldn’t be subject to these conditions. Instead, they’d be free floating from autonomous submersibles, which would tow the farm through the ocean, adjusting their depth based on the needs of the kelp, Navarrete tells me.

“The submersibles could be programmed to bring the whole farm back to a harvester location,” he says.

To know whether kelp farms could thrive in the open ocean, though, scientists needed to see how “depth-cycling” impacted growth. And that’s where the kelp elevator came into play.

Kelp fronds are beautiful to behold under water and might save the planet.

Ashley HarrellIn essence, the elevator consists of a large, open platform featuring long poles from which the kelp grows. The platform is attached to a buoy by a cable, and a winch allows the system to be raised and lowered each day. The idea was to give the kelp the two things it needed: exposure to sunlight near the surface during the day, and time to absorb nutrients from the cooler water below, at about 260 feet deep, at night.

The scientists were divided over whether it would work, Navarrete says. “Some people were really confident. Some people thought it was crazy. I was like, I just don’t know,” he says. “I gave it a 50-50 chance.”

Whether the kelp could thrive at varying depths hinged on two questions: Would pressure changes damage the algae and keep it from growing? And was the sunlight somehow facilitating nutrient uptake, meaning the kelp would be unable to absorb nutrients down below?

The team was thrilled to discover that the answer to both of those questions was no.

Senior scientist Diane Kim conducts research on a kelp frond.

Courtesy of Maurice Roper/USC Wrigley Institute“When we got the first pictures from the divers, the kelp looked like it was growing, so that was pretty exciting,” Navarrete says. Once all of the data had been collected, the scientists were amazed to see that the depth-cycled kelp yielded four times more biomass than kelp grown in beds without depth-cycling.

Their findings were published in the journal Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, and new phases of the research are now looking at growth rates, kelp genetics and growing kelp from seedlings on the elevator, rather than using transplanted kelp.

While it’s all pretty interesting, Navarrete emphasizes that kelp farming still has a long way to go before it can save the planet. He’s seen a lot of “boosterism” from entrepreneurial types — already, corporations are looking to buy carbon credits for farmed and sunk kelp, despite the fact that the method is still untested.

He’s been around scientists who are skeptical about the promise of kelp but appreciate the money that’s coming in for research projects. Once again, Navarrete finds himself somewhere in the middle. “I don’t know,” he says. “It could work?”

What we need now, he says, is a commercially viable way to ramp up production. It would help if people suddenly developed a taste for giant kelp, but up to this point, few Americans have shown interest in eating it, Navarrette says.

Whether or not kelp takes off and saves the world is anybody’s guess. But for now, while we’ve still got some right off California’s shores, I highly recommend swimming with it.

[ad_2]

Source link