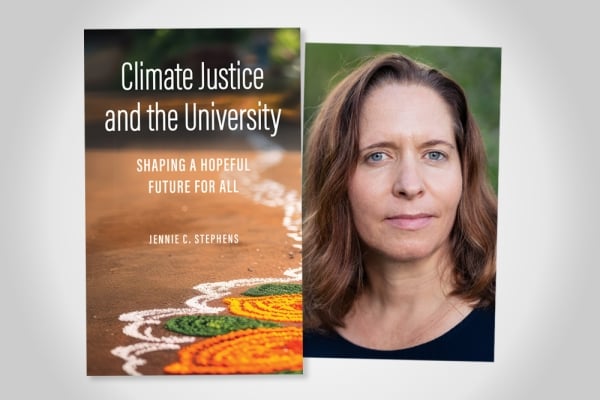

What is a climate justice university, and how can our universities transform into institutions that truly promote the well-being of the earth and humanity? Jennie C. Stephens’s new book, Climate Justice and the University: Shaping a Hopeful Future for All (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2024), sets out to answer that question. It outlines where today’s universities fall short in their handling not only of the climate crisis but also a wealth of other modern social issues.

The book lays out broad ideas for transforming how universities function in society, such as shifting research practices to collaborate with people and communities affected by the issues, like the climate crisis, at the center of that research. Stephens, who is a professor at both the National University of Ireland Maynoonth and Northeastern University, acknowledges in the introduction that such a transformation would be a major undertaking, and one that many universities would be disinclined to tackle. “Because of the internal pressure within higher education to maintain institutional norms, this book and its proposal for climate justice universities are, in some ways, radical acts of resistance,” she writes.

In a phone interview, Stephens spoke with Inside Higher Ed about her vision for climate justice universities—and how modern institutions fail to meet it. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: It was interesting reading that your perspective on these issues comes both from your scholarly work and from a time that you worked on the administrative side of academia. Could you describe how those experiences came together to inspire this book?

A: I’ve been working in academia my whole career—more than 30 years—and during that time, I’ve been focused on climate and energy issues and sustainability from a very social justice perspective. What has happened through my experiences over time is that I see part of society’s inadequate response to the climate crisis mirrored in academia.

I think higher education has a really big role in society—in what we are doing and what we’re not doing, in how we’re teaching and learning, in what we’re doing research on and what we’re not doing research on—and I think that our collective insufficient response to the climate crisis is related to what’s been happening in our higher education institutions, which are increasingly very financialized. They’re driven by profit-seeking priorities and new tech and start-ups and focused on job training. We’ve drifted away from a public-good mission of higher education: What does society need in this very disruptive time, and how can our higher education institutions better respond to the needs of society, particularly of vulnerable and marginalized communities and people and households who are increasingly struggling with all kinds of precarity and vulnerabilities?

Q: How would you define the term “climate justice university”?

A: The idea of a climate justice university is a university with a mission and a purpose to create more healthy, equitable, sustainable futures for everyone. So, that is a very public-good mission. The idea is to connect the climate crisis with all the other injustices and the … multiple different crises that are happening right now; the climate crisis is just one among many. We also have a cost of living crisis; we have a mental health crisis, we have financial crises; we have a plastic pollution crisis and a biodiversity crisis; we have a crisis in international law and a militarization crisis. We have all of these crises, and yet what we’re doing in our universities tends to continue to be quite siloed and trying to address parts of specific problems, rather than acknowledging that these crises are symptoms of larger systemic challenges.

For me, climate justice is a paradigm shift toward a transformative lens, acknowledging that things are getting worse and worse in so many dimensions, and that if we want a better future for humanity and for societies around the world, we actually need big, transformative change. A lot of things we do in our universities are reinforcing the status quo and not promoting or endorsing transformative change. So, climate justice is a paradigm shift with a transformative lens that focuses less on individual behavior, more on collective action, less on technological change, more on social change, and less on profit-seeking priorities, more on well-being priorities. What do human beings need to live meaningful, healthy lives, and how can society be more oriented toward that?

Q: Can you talk a bit more about how the current structure of the university maintains the status quo with regard to climate?

A: One of the ways that I think universities kind of perpetuate the status quo is by not acknowledging what a disruptive time we’re in with regard to climate crisis, but other crises as well. There’s an encouragement on many campuses for kind of being complacent, like, “Oh, this is the way the world is.” Not necessarily encouraging students and researchers to imagine alternative futures.

There’s also a focus on doing research that billionaires or corporate interests want us to do, and—in particular, in the climate space—what this has led to is a lot of climate and energy research that is funded by big companies and other wealthy donors who actually don’t want change. We have more and more research to show who has been obstructing climate action and transformative change for a more stable climate future. We know many of those same companies and same fossil fuel interests have also been very strategically investing in our universities. What that does is constrain the research and also the public discourse about climate and energy futures toward very fossil fuel–friendly futures.

Early on in my own career, I worked on projects that were funded by the fossil fuel industry on carbon capture and storage, and a lot of the climate and energy research in our universities is focused on carbon capture and storage, carbon dioxide removal technology, geoengineering—all these technical fixes that assume we’re just going to keep using fossil fuels. What we really need, if we had more climate justice universities that were focused on the public good and what the climate science has been telling us for decades, is to phase out fossil fuels. We need a global initiative to phase out fossil fuels. But we don’t have in our universities much research on how to phase out fossil fuels.

Q: In your book, you discuss the concept of exnovation—the process of phasing out inefficient or harmful technologies. Why is research into exnovation not already more common in higher education, and what are the main barriers for researchers who want to take this approach?

A: I do think funding has a lot to do with it. There’s a whole chapter in the book about the financialization of higher education institutions, which has resulted from kind of a decline in public support toward more private sector support, which means that universities are beholden to private sector interests, increasingly, and they’re encouraged and incentivized to cater to and partner with … private sector interests. I think that has really changed the kinds of impact that higher education institutions and research has had.

Of course, there are a lot of people within universities who are interested in the public good and doing research on exnovation. But the incentive structure, even among those of us who would want to contribute in those ways, is such that we are increasingly incentivized and promoted based on how much money we can bring in, how many papers can we get published and the scale of resources available to do research. So, there’s a larger, long-term strategy to orient research toward the technical fixes, particularly when it comes to climate and energy, and a lot less funding available for social change or governance research on how to bring back the public-good priorities in our policies, our funding, in our universities. It’s really a longer-term trend that has led to this financialization.

Q: You lay out a lot of alternative ideas for financing universities, which is important given that anxiety over funding is at an all-time high at some institutions. Walk me through some of your ideas and talk about the feasibility of restructuring how universities are funded.

A: One idea in the chapter on new ways of engaging and being more relevant is what if we imagine higher education institutions more like public libraries? Public libraries, we all kind of recognize as valuable resources for everyone; every community should have some access to a public library. What if higher education could be [better] invested in that sense of being a resource and not being an ivory tower that is really hard to get into and only some privileged people get access to? What if our higher education institutions were designed and funded to provide more accessible and relevant resources, co-created with communities? That’s kind of one of the big ideas of imagining what this really valuable resource could be more relevant and more connected to the needs of society and of communities.

You also asked about feasibility, and one of the things that I want to point out is that this book is not a how-to; every context and region and different place in the world has different things going on with their higher education institutions. The idea with this book is to invite us all to kind of think about, what is the purpose of higher education institutions? And how can we better leverage all the public investment that is already spent on higher education institutions? How can that be oriented toward better futures for everyone?

At higher education institutions that are feeling very vulnerable, having a lot of anxiety about funding levels—the ideas in this book don’t provide a prescription on how to fix that in the near term. But the ideas in the book are really to encourage us all—and especially those involved in higher education policy and higher education funding—to re-evaluate and reclaim the public-good mission of higher education and reconsider how to restructure higher education so that the value and the resources are more accessible, more relevant and more transformative, in terms of fitting the needs of a very disruptive time for humanity and for societies and communities around the country and around the world.