Miranda Lambert grinned as she stood on the smallest stage she’s played in years. She’d just debuted an irreverent, rowdy hook—“Are we in love, or are we just drunk?” from “Bitch on the Sauce (Just Drunk)”—to the thrilled screams of 180 dedicated fans, who were mostly decked out in Miranda shirts, sparkles, fringe, or all three. They had spent hours in the August heat, waiting for the intimate show at Stubb’s Bar-B-Q, in Austin, the same spot where Lambert had played her first major-label showcase, almost exactly twenty years ago.

“It was the first time I drank a beer onstage. I was underage, but I was nervous,” she told the audience. Dressed in boots, a cowboy hat, a denim skirt, and a tight black T-shirt bedazzled with the venue’s name, she motioned to a cup within reach before adding, “It started a bad trend.”

Her homecoming went beyond the concert at Stubb’s. “This is full circle,” Lambert said more than a few times during the set. “We’ve gone out and accomplished so much, but my heart lives in a honky-tonk no matter what.” This was a honky-tonk show (it said so on the souvenir tickets) and a return to the brand of music she came up making.

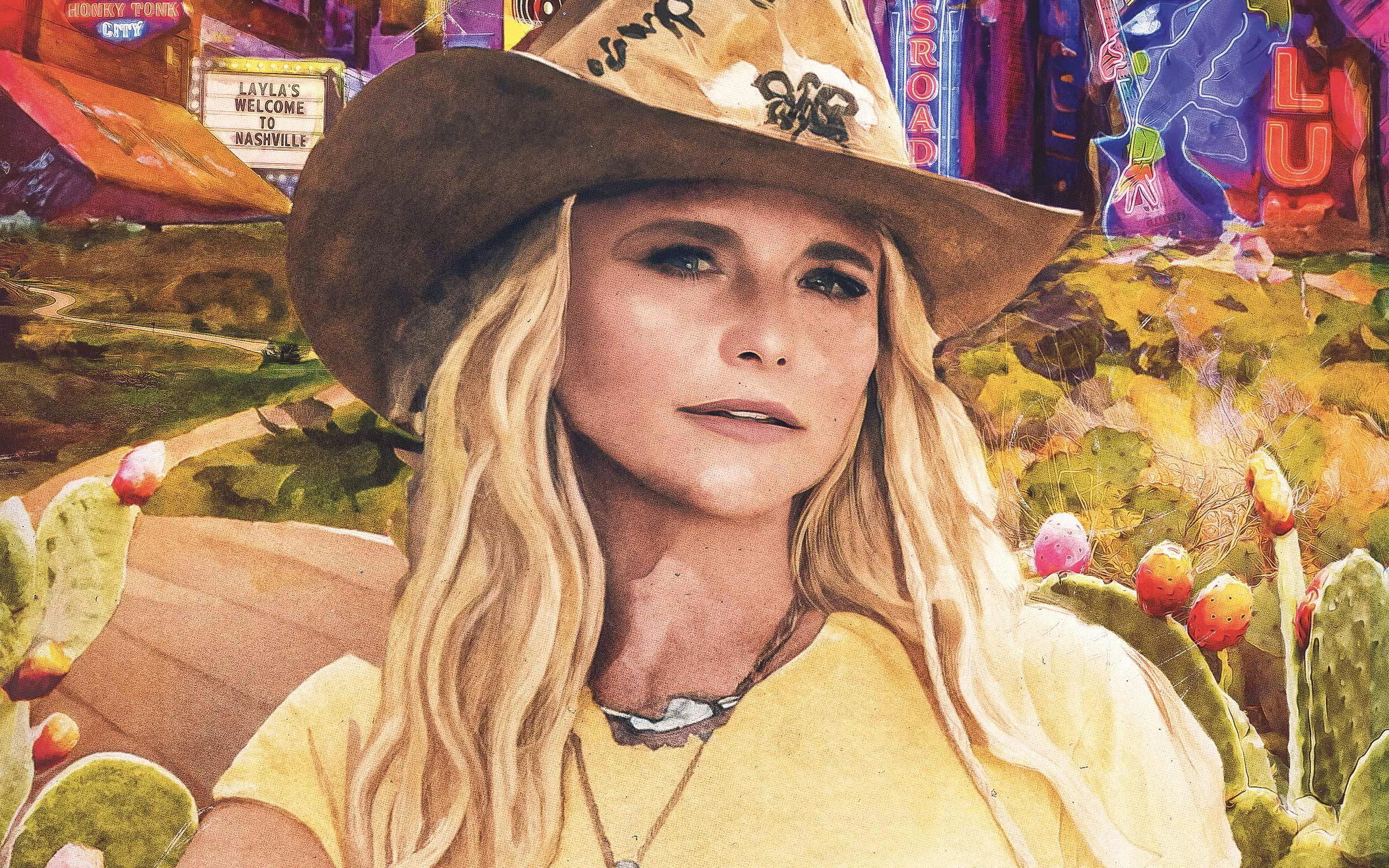

On paper, Lambert seems to have all she ever wanted and more: a loyal fan base of mostly women, as well as the respect of Willie Nelson, George Strait, and most of Texas country’s patriarchy; a home on sprawling, wooded farmland south of Nashville and another in the heart of Austin; the success of a glitzy Las Vegas residency and a line of home goods at Walmart; number one singles and critically acclaimed albums. Her latest, a collection of fourteen songs called Postcards From Texas, released September 13, is her tenth major-label record—and hopes are high that it will become her seventh to go platinum. Rather than taking a victory lap, though, Lambert is pushing into territory that’s as risky as it is familiar, and fighting for a place in the scene where she began chasing her dreams two decades ago.

Postcards is the first album she’s recorded in a Texas studio since she was eighteen, shortly before she headed to Nashville to give Music Row a shot rather than continue the honky-tonk grind in her home state. She’s also settling in as cofounder of Big Loud Texas, a new outpost of the massively successful Nashville shop Big Loud, aimed at developing artists who—like Lambert—could bridge the gap between country’s competing capitals.

Having spent much of her career currying favor with corporate radio and the country establishment, Lambert is now betting on the Lone Star State to claim her as forcefully as she’s always claimed it—to help her prove that a woman can indeed have both the reach of a Nashville star and the credibility of a Texas outlaw.

“I just signed a new record deal at forty years old,” she told the Stubb’s crowd, with pride and disbelief in her voice. A joint deal with Republic Records and Big Loud came more than a year after a breakup with Sony left her longing for home. Coincidentally, Willie Nelson was also forty when he switched labels and released his homecoming album, Shotgun Willie, ushering in the most revered era of Texas country music’s history.

“But,” Lambert continued, “I still have that same fire that I had at that show in 2004.” With that, she dabbed delicately at her cheeks, trying not to disrupt layers of false eyelashes. “I’ll get all teary talking about honky-tonks,” she explained, before strumming into another hard-swinging, two-step-ready tune.

You might think, this being a Texas music event, why is this guy gonna talk about a Nashville artist?” Lambert’s father, Rick, said during an appearance at the inaugural Fort Worth Music Festival and Conference, in early 2023, before launching into his daughter’s origin story. “Well, Miranda grew up in a town of five thousand people, in Lindale, Texas. That’s a good start for being a Texas artist.”

Lindale, known mostly for being a halfway point for Dallas drivers heading to the casino riverboats in Shreveport, hasn’t changed much since Rick and his wife, Beverly, raised Miranda and her younger brother, Luke, there. A few more residents have moved in, and a lot more Lambert-related attractions have popped up: veer off Interstate 20 when you see the “Hometown of Miranda Lambert” billboard and head straight to Miranda Lambert Way, where you’ll find her Pink Pistol boutique and her parents’ Red 55 Winery. Those who make the pilgrimage can stock up on Miranda merch—a pack of postcards, one for each song on her new album, goes for $17.99—and sip wines named after her songs, such as a “Vice” malbec or a “Kerosene” pinot grigio.

As Skip Hollandsworth chronicled in a 2011 Texas Monthly profile, Lambert learned guitar and songwriting from Rick, a former Dallas Police homicide detective and private investigator. “I still only know like four chords,” she quipped during a recent interview, “because Dad said that’s all I needed.” Those chords got her all the way to Nashville, where she’s sitting in her manager Marion Kraft’s sleek office on Music Row. There’s not a trace of cowboy kitsch in the airy space except on Lambert, who’s clad in a blue paisley maxi skirt from her Idyllwind clothing line (sold at Boot Barn), a simple white tank top, loads of turquoise, and (of course) Idyllwind cowboy boots.

She may be selling them now, but Lambert earned those boots. After graduating from high school early to pursue music, she landed a job at the Reo Palm Isle in Longview, performing four hours a night, three nights a week. With what she learned there, a teenage Lambert hit the road with her parents in tow, taking gigs at any venue that would have her and sometimes begging to get onstage. The family would pull up to shows just to see if she could play between sets, and Lambert would polish her go-to covers—Emmylou Harris, Kelly Willis—while crews wound cords and set up mics. During a stop at Blaine’s Pub, in San Angelo, the soundboard broke, and Lambert performed an acoustic set for an hour, trying to keep the drunken customers calm. “I played Charlie Robison’s ‘My Hometown’ like three times,” she recalls. “I didn’t know that many songs, and it won every time—like, beers in the air.”

At dance halls, dives, and rodeos—and even a kickoff party for a Dallas Cowboys training camp—Lambert fought for time in the spotlight and eventually started opening for bigger acts: Jack Ingram, Reckless Kelly, Cross Canadian Ragweed, and, during one wild show at the Gypsy Tea Room, for Willie. Lambert recorded an independent, rough-around-the-edges album in a garage studio in Garland, in North Texas, and two songs made the local charts: “Well I can rope a steer / Drink a keg of Lone Star beer / I got three pet armadillos and a pickup truck,” she sings on “Texas Pride.” She sold her record, along with straw hats she had decorated, out of the back of her parents’ Ford Expedition.

Many nights, she was the only woman singing onstage. Early on, however, she shared a microphone with another East Texan, Kacey Musgraves, who grew up about twenty minutes north of Lindale, in Golden, and whose family knew the Lamberts. Musgraves’s grandmother Barbara, of all people, made a call that wound up changing their lives. “I think this would be great for Miranda,” she told Rick and Beverly in 2003, sharing details of the upcoming Dallas auditions for a new reality show called Nashville Star.

This was a fork in the road for Lambert, who was forced to make a choice that she’d been dreading. “I was coming up at that time where it was sort of, like, middle finger to Nashville. And it scared me to death,” she recalls in her manager’s office of the long-ago decision to leave Texas. “I was like, ‘Why do I have to pick one?’ ” She had been doing it in what Texas songwriters might call the Texas way, gaining fans one at a time, rather than succumbing to the slick Music Row machine. But it had been an uphill climb, one that was steeper because of her gender: if there’s a country music scene less female-friendly than Nashville’s, it’s the one in Texas, where successful women remain the exception in a culture dominated by men. The talent bookers Lambert encountered in her early days proved it.

“They would flat out tell my mom, ‘Well, we don’t hire girls. Girls don’t draw,’ ” Lambert recalls, her deep twang becoming more exaggerated as she mimics promoters. “My dad was giving people fifty bucks to let me get onstage,” she adds with a laugh.

“It’s tougher than it should be,” says Brendon Anthony, the vice president of Big Loud Texas, who saw Lambert sweet-talk her way into performing at dance halls along the Texas circuit when he was a fiddler in Pat Green’s band.

Lambert wasn’t interested in American Idol, despite fellow Texan Kelly Clarkson’s sudden success the year before, because contestants didn’t sing original songs. She was skeptical of its country cousin too, but Beverly pushed her daughter to audition for Nashville Star. It took two cattle calls, one in Dallas and one in Houston, for Lambert to earn a spot on the show because her heart wasn’t in it at the first audition. Even though the nineteen-year-old came in third (notably, behind two men whose achievements in music don’t come close to hers), the show earned her a record deal.

A surprise debut at number one on the country albums chart with the decidedly un-Nashvillian Kerosene—written by Lambert with help from other songwriters, including Rick—soon followed. What she’s done since is well-documented: Grammys, number one songs, platinum albums, and the most Academy of Country Music Awards in history.

The triumphs obscure how unlikely her trajectory has been. “I don’t know of any female that has moved to Nashville in the past fifteen years trying to do country music that wouldn’t say Miranda has influenced them, whether it’s her songwriting, her singing, her stage presence,” says Lainey Wilson, whose latest album includes a duet with Lambert. “She has paved the way for folks like me to be able to do what I do.”

The music itself stands apart from Lambert’s long résumé. In a genre that has long been singles driven, her collection of albums encompasses the full range of what modern country music can be. Lambert is a sharp songwriter who juggles sly wit and piercing emotion—all delivered in her potent, nasally twang.

That combination has allowed Lambert to chase radio, though she has her art-first, commerce-later projects too. In Nashville, the Pistol Annies, her trio with Ashley Monroe and Angaleena Presley, create sugar-sweet harmonies to gussy up their cheeky lyrics. And in Texas, she has Ingram and Jon Randall, her collaborators on 2021’s intimate, acoustic campfire album, The Marfa Tapes. “She’s one of the best songwriters by herself,” Monroe says. “She has something that is unlike anybody else.”

“She’s a stud,” Ingram adds. He cracks up, remembering when they were writing some “smart-ass song” and he suggested they include the line “shake your moneymaker.” “She looked at me like she was gonna spit,” he says. “She said, ‘No, I would never say that, Jack, and neither would you. G—damn.’ ”

Mastering the acrobatics required to deliver songs for radio so she can record a Susanna Clark or Fred Eaglesmith tune has been Lambert’s challenge. So has doing the dance of award shows and press for the privilege of being recognized in “female” categories. Sexism in country radio has been an issue for years, with labels and program directors perennially blaming each other for the dramatic gender discrepancy in what gets played on the air. Women made up just 11 percent of the artists played on country radio in 2022, and as of press time, all eighteen songs that have topped the country airplay chart in 2024 are by men.

“It’s not been a pretty road for me,” Lambert says of her experiences at radio. “There’s been some highs, and then there’s been some knock-down, drag-out battles that I didn’t win, that my songs just couldn’t win.” She has had only four solo number one hits on Billboard’s country radio airplay chart. By comparison, Luke Combs has had fifteen songs reach the top of the same chart, starting with his 2016 debut single. “Certainly, for male artists, it’s just a different path,” Lambert acknowledges. “I’ll watch it, and sometimes I’m like, ‘Damn, that happened quick.’ ”

Back in promo mode for Postcards, Lambert says she’s “anxious because I know it matters.” At press time, “Wranglers,” the lead single from the album, had barely scraped the bottom of country radio’s Top 40 after seventeen weeks. “I’m faithful to country music, and I love it so much,” she says. “But there’s certain things I’m just not willing to do anymore to claw my way up.”

Interviews, photo shoots, videos, and, in Lambert’s case, appearing on more than a few tabloid covers are other parts of the job that she has learned to take in stride. “Getting more popular and going through a very public divorce [she and Blake Shelton split in 2015], that was a whole different light that I did not ever count on,” she says. “I’ve struggled with ups and downs with my weight over the years, and . . . you don’t get to call in insecure to work. Some days I’m like, Can I call in sad? No. Can I call in insecure? No. Can I call in fat? No. I just have to go and do it. Unless I physically can’t sing, I’m going to work. It teaches you a lot of stamina and discipline and grittiness.”

Postcards From Texas is not a Nashville record. It was recorded with mostly Texas musicians at the historic Arlyn Studios, in Austin—“stumbling distance,” as Lambert puts it, from her home in the Travis Heights neighborhood. “The days were more laid-back,” she recalls. “Really chasing the songs down, not feeling rushed or like, ‘We’re trying to get a single, we’re trying to get a hit.’ That felt like creative freedom.”

She and Randall coproduced the album, bringing into the studio Texas artists such as Bukka Allen (Terry Allen’s son), Lloyd Maines (Natalie Maines’s dad), and drummer Conrad Choucroun. “They don’t play in Nashville, on demo sessions, every day, and so they’ve got a whole different set of creative tools,” Randall says. Steel guitar runs through the album, bringing together raucous honky-tonk numbers and moody ballads. Postcards will sound familiar to fans; this is not a radical departure. But for Lambert, it’s personal—a musical ride that is as introspective as it is proudly Texan.

The record includes credits as diverse as outlaw country legend David Allan Coe (her mom babysat his four-year-old daughter in Dallas back in the day) and Lambert’s husband, Brendan McLoughlin, a former New York City police officer. In the middle of the pandemic lockdown in 2020, a bored Lambert told McLoughlin, “I bet you could write.” They penned half a dozen songs. “He has a lot of life experience, and that’s what you draw from,” she says. He was watching football on mute while Lambert and Randall were writing “Dammit Randy,” another Postcards track, and he kept throwing out suggestions for lyrics. “He has some of the best lines,” she insists. She’s not wrong: “I was flyin’ a kite in the middle of a hurricane / Tied to the tracks like a penny waitin’ on a train” are lyrics her husband wrote.

As she’s releasing a record about “coming home,” Lambert also has her role at Big Loud Texas—what she and Randall imagine as a link between Music Row and the state that made her. “We want to change the tone,” she says. “I want to be a Texas artist, but I also want to play everywhere else, and I want Big Loud Texas to be a home for that.”

“As long as there’s been commercial country music, Texas talent has fed the Nashville intellectual property machine,” says Brendon Anthony, who was the director of the Texas Music Office before joining Lambert and Randall. Record executives in Nashville think they know what to do with Lone Star talent, he says, while the artists feel like they can do it all themselves right here at home. The label, he believes, will be a “translator between two worlds,” something that is “legitimately rooted in Texas” but still tied to the “radio and marketing juggernaut in Nashville.”

Its goal is to create a path to national country stardom that begins and ends in the Lone Star State. “If we get this right, we can facilitate a business that doesn’t make Texas artists or writers feel like they’re having to sell out and come to Nashville to get their music out beyond Texas,” Randall explains. Austin native Dylan Gossett is the first (and so far only) musician signed to the label. But the trio are already thinking beyond their roster. “Why is there no infrastructure?” Randall asks. “There’s incredible studios, great artists, great engineers, and no one is working together.”

Lambert envisions a brick-and-mortar space in Austin or Fort Worth that fosters creativity and collaboration. A “Cheers moment,” she calls it, “but for songwriting.” Mostly she wants to share the wisdom she’s gained over two decades in the business. “The first question is like, ‘What are your biggest, wildest dreams?’ ” she says, lighting up as she acts out a conversation with potential country signees and, eventually, artists of other genres. “Let’s shoot for the moon and then find the path to get there.”

Strolling through her manager’s Nashville office, Lambert sheepishly points out walls covered in plaques that feature her likeness. The rest of her awards, including a legion of trophies, are tucked away in the music room of her Tennessee home. “It’s weird to have your face everywhere,” she says, wrinkling her nose. The office also has a vast closet where her costumes and red-carpet looks are archived and cataloged, as well as a wood-paneled bar, where, she eagerly points out, she recently wrote a song with the Conroe-raised Parker McCollum.

Music still comes first—and for Lambert, little has changed in how she thinks about it. The zeitgeist, though, has shifted: country and its culture are trendy enough to leave their mark on the charts, film, TV, and fashion. Lambert is as happy to embrace country’s newcomers as she is to be ahead of the curve. “I don’t care how you got here; I’m just damn glad you’re here,” she says. “Welcome, let us show you the steel guitar. You can be a cowboy of any kind.”

That open-mindedness about claiming the country label is another way Lambert draws from the outlaw tradition of her home state. “Miranda is in that Willie Nelson echelon of truly unique artists,” says Ingram, “and when it comes to Nashville or Texas, I always was very aware that Willie made most of his records in Nashville.”

It’s also where Lambert racked up her massive sales and built an international fan base—but without as many radio hits as one would expect from an artist of her longevity and consistency. Back in the Lone Star State, she earned honky-tonk bona fides early on and now goes out of her way to support Texas country musicians—but many of their authenticity-obsessed fans don’t consider her an icon. Even if those caveats reflect the tired sexism that still lurks in country music, Lambert likely won’t be deterred from pursuing the sound and the success she craves. After all, the hard truth is that if she had stayed in Texas, this story would never have been written.

“It’s just a longer road” to stardom for women in Texas country, says Lambert. “It’s not a bad thing or a good thing. It just is what it is.” She is looking forward, staying the course by heading home as she stretches between two realms of country music. It’s the way Waylon and Willie and the boys did it, along with all the defiant, singular Texas singer-songwriters that came after them—by building the legend one show, one song, one great line at a time.

Natalie Weiner is a Dallas-based writer who has covered music and sports for the New York Times, the Washington Post, Rolling Stone, Billboard, and more. She also cofounded the newsletter Don’t Rock the Inbox.

This article originally appeared in the October 2024 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The ‘Return’ of Miranda Lambert.” Subscribe today.