Humans don’t know what they’re missing under the surface of a busy shipping channel in the “cruise capital of the world.” Just below the keels of massive ships, an underwater camera provides a live feed from another world, showing marine life that’s trying its best to resist global warming.

That camera in Miami’s Government Cut is just one of the many ventures of a marine biologist and a musician who’ve been on a 15-year mission to raise awareness about dying coral reefs by combining science and art to bring undersea life into pop culture.

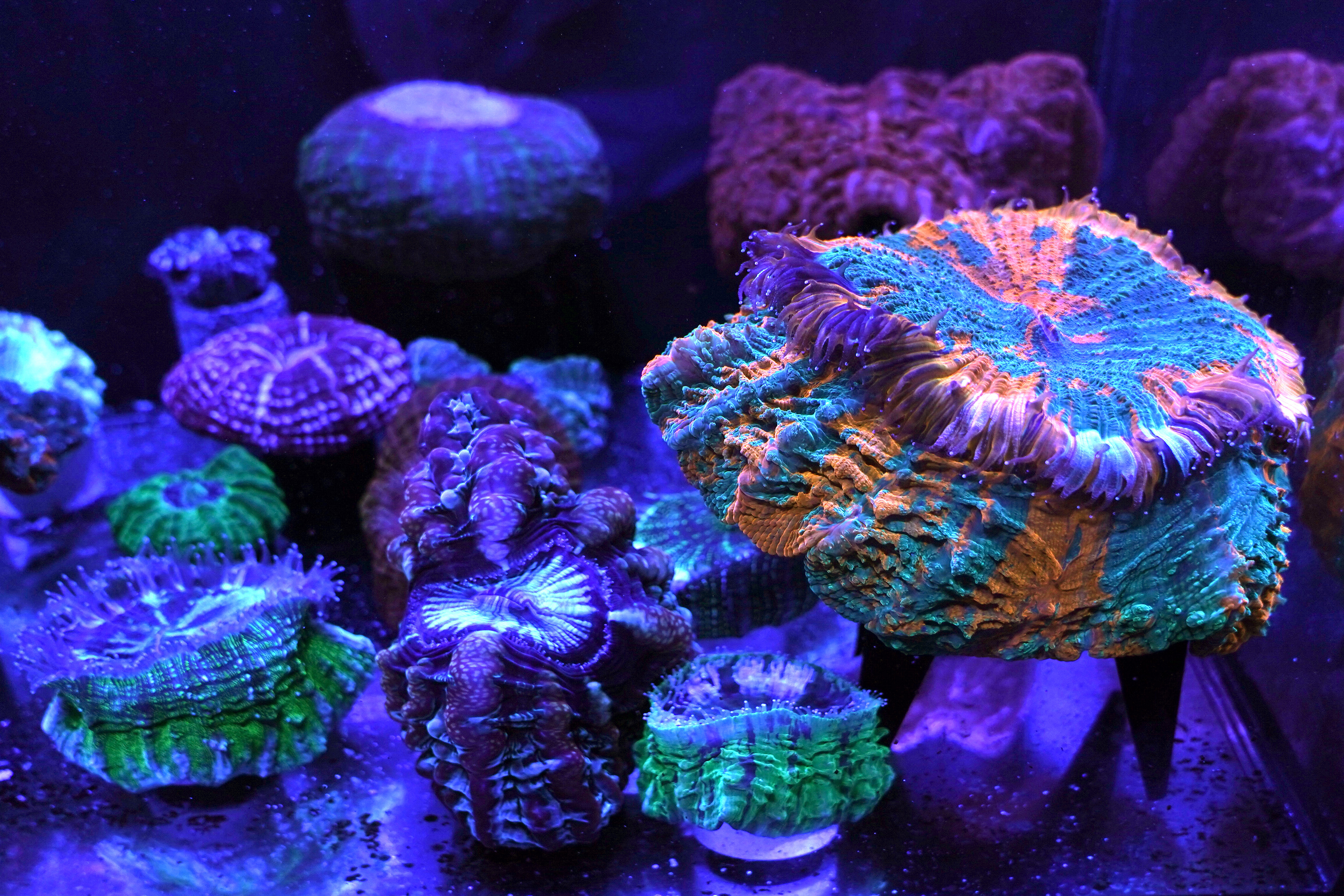

Their company — Coral Morphologic — is surfacing stunning images, putting gorgeous closeups of underwater creatures on social media, setting time-lapsed video of swaying, glowing coral to music and projecting it onto buildings, even selling a coral-themed beachwear line.

“We aren’t all art. We aren’t all science. We aren’t all tech. We are an alchemy,” said Colin Foord, who defies the looks of a typical scientist, with blue hair so spiky that it seems electrically charged. He and his business partner J.D. McKay sat down with The Associated Press to show off their work.

One of their most popular projects is the Coral City Camera, which recently passed 2 million views and usually has about 100 viewers online at any given time each day.

“We’re going to actually be able to document one year of coral growth, which has never been done before in situ on a coral reef, and that’s only possible because we have this technological connection right here at the port of Miami that allows us to have power and internet,” Foord said.

The livestream has already revealed that staghorn and other corals can adapt and thrive even in a highly urbanized undersea environment, along with 177 species of fish, dolphins, manatees and other sea life, Foord said.

“We have these very resilient corals growing here. The primary goal of us getting it underwater was to show people there is so much marine life right here in our city,” Foord said.

McKay, meanwhile, sounds like a Broadway producer as he describes how he also films the creatures in their Miami lab, growing coral in tanks to get them ready for closeups in glorious color.

“We essentially create a set with one of these aquariums, and then obviously there’s actors — coral or shrimp or whatever — and then we film it, and then I get a vibe, whatever might be happening in the scene, and then I soundtrack it with some ambient like sounds, something very oceanic,” McKay explained.

Their latest production, “Coral City Flourotour, ” will be shown on the New World Center Wallscape this week as the Aspen Institute hosts a major climate conference in Miami Beach. Foord is speaking on a panel about how the ocean’s natural systems can help humans learn to combat impacts of climate change. The talk’s title? “The Ocean is a Superhero.”

“I think when we can recognize that we’re all this one family of life and everything is interconnected, that hopefully we can make meaningful changes now, so that future generations don’t have to live in a world of wildfires and melted ice caps and dead oceans,” Foord told the AP.

Their mission is urgent: After 500 million years on Earth, these species are under assault from climate change. The warming oceans prompt coral bleaching and raise the risk of infectious diseases that can cause mass die-offs in coral, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Stronger storms and changes in water chemistry can destroy reef structures, while altered currents sweep away food and larvae.

“Climate change is the greatest global threat to coral reef ecosystems,” NOAA said in a recent report.

That gets at the second part of Coral Morphologic’s name. “What does it mean to be morphologic? It really means having to adapt because the environment is always changing,” Foord said.

The staghorn, elkhorn and brain coral living in Government Cut provide a real-world example of how coral communities can adapt to such things as rising heat and polluted runoff, even in such an unlikely setting as the port of Miami. Their video has documented fluorescence in some of the coral, an unusual response in offshore waters that Foord said could be protecting them from solar rays.

“The port is a priceless place for coral research,” Foord said. “We have to be realistic. You won’t be able to return the ecosystems to the way they were 200 years ago. The options we are left with are more radical.”

Beyond the science, there are the clothes. Coral Morphologic sells a line of surf and swimwear that takes designs from flower anemones and brain coral and uses environmentally sustainable materials such as a type of nylon recycled from old fishing nets.

“We see the power of tech connecting people with nature. We are lucky as artists, and corals are benefitting,” Foord said.

Dr. Elizabeth Madin and Dr. Joshua Madin met and fell in love through their shared passion for saving the oceans. Today, they are marine ecologists with the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology attacking the same problem from different angles —preserving the world’s dying coral reefs.

Jackson reported from Miami and Anderson from St. Petersburg, Florida.