If most of us were to stumble upon six inches of spiked, segmented worm flesh during a leisurely walk along the beach, we’d react, at best, with “eww.” But when Jace Tunnell was beachcombing just north of Mustang Island State Park, in mid-August, and found a marine polychaete—also known as a bristle worm or fireworm—on a barnacle-covered log that had washed ashore, he was as excited to see that bad boy as that bad boy had once been excited to see the barnacles on that log. (Fireworms feed on barnacles.)

Tunnell serves as the director of community engagement at Texas A&M–Corpus Christi’s Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies, and as such, he beachcombs every week, bringing along a GoPro HERO11 so he can snap photos of the things he finds and film his popular Beachcombing With Jace Tunnell YouTube series. You might be familiar with his work on something infinitely more terrifying than a sea worm—washed-up baby dolls—which made it to Last Week Tonight With John Oliver.

When Tunnell found the fireworm, he’d been planning to devote that week’s video to the gooseneck barnacle, which is often found on the debris that washes up along the Gulf Coast (a related species is an expensive delicacy in Spain and Portugal). “The log that I was looking at was perfect for it, because gooseneck barnacles were covering the entire thing,” he recalls. “And right before I was about to leave, I looked down and saw the brown worm. I knew exactly what it was because you could see the white bristles.”

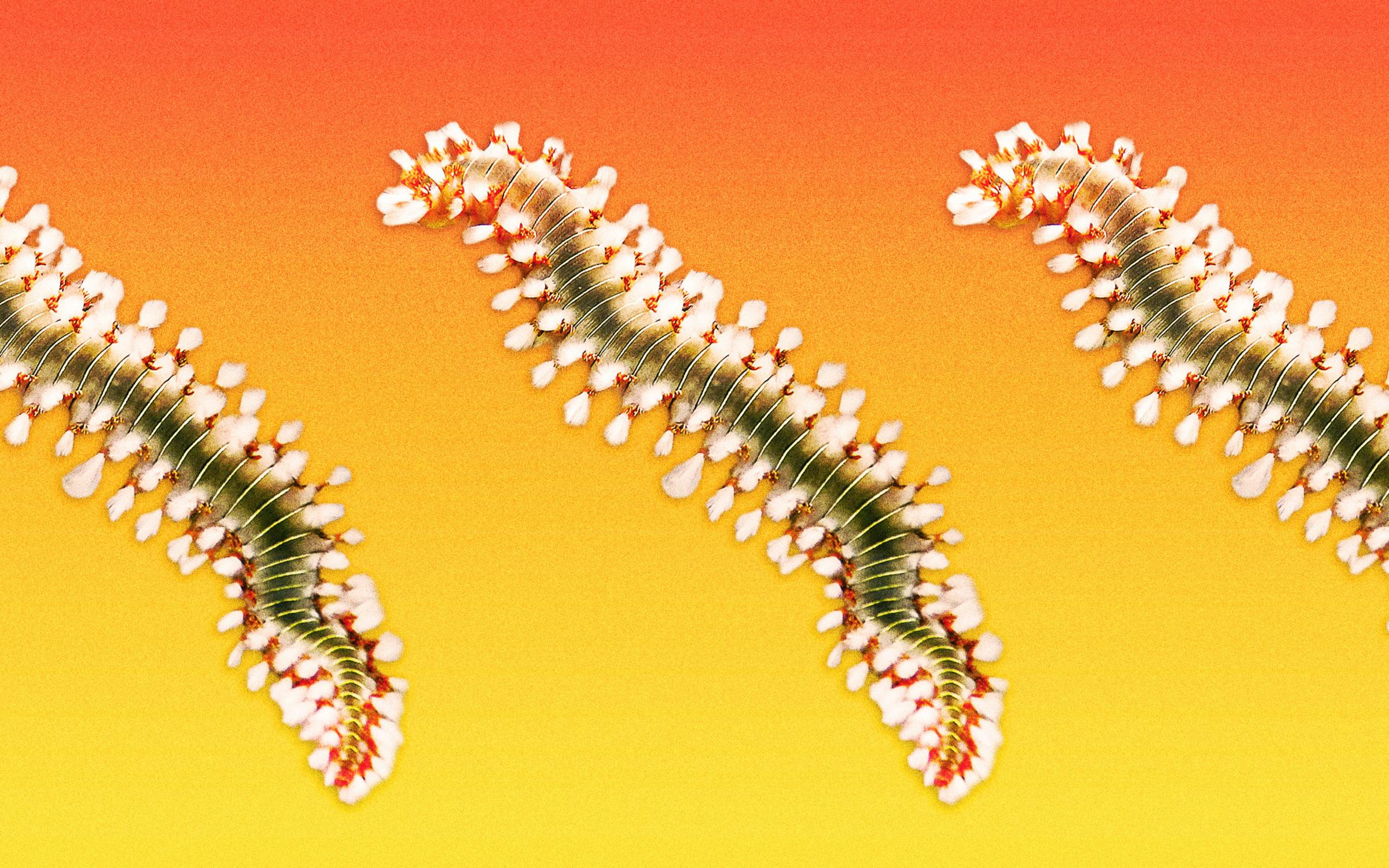

Bristle worms got their colloquial name from the cactus needle–like spikes that run along each of their sides. A staggering ten thousand or so species in oceans across the globe belong to the polychaete class; the one Tunnell found, Amphinome rostrata, is from a family with 28 different species. “This particular one doesn’t even have a common name to it,” says Tunnell. “That’s why we just call it a fireworm.”

That moniker does a better job expressing what those bristles can actually do. Like cactus needles, the bristles are defense mechanisms that release from appendages called parapodia whenever the worms feel threatened. They will stick you and release painful neurotoxins into your skin that can cause severe pain, dizziness, and nausea, sometimes lasting for several hours. The bristles are also incredibly small (one Reddit user called a fireworm a “fiberglass sea caterpillar”), and the worms have a tendency to release numerous bristles at a time. Hence the fiery nickname.

Tunnell says there’s no particular time of year when these things come ashore more frequently. A few years ago he found one one clinging to a decoy duck during winter. It really is just about the debris, and the amount of debris that washes up has more to do with tides and wind than temperature and season.

The good news is that, unlike the similarly named ant we know all too well, the fireworm is not a threat humans come up against frequently. “I get excited, but a lot of people are like ‘I’m never going in the water again,’ ” says Tunnell. “But really, these aren’t going to wash up on the beach. They’re going to be on an item, and they’re going to be crawling around looking for somewhere dark or moist to hide in,” he adds.

You won’t encounter a fireworm simply while swimming. You’d have to be on the lookout, turning over debris, and even then, once you’re surprised by the presence of a fireworm, you’d almost certainly have to want to touch it in order to risk any pain.

I don’t know many who would be compelled to do such a thing, other than the handful of obnoxious dudefluencers who provoke venomous creatures on purpose for clicks. In Texas in particular, it is wise to avoid direct contact with creepy-crawlies. If you see something strange on a beach, don’t pick it up, even if it’s a really beautiful shade of blue. This guideline applies on land, too, where our most pain-inducing creatures may also be our cutest.