Instead of viewing these natural tendencies as liabilities, Achim Menges, an architect and professor at the University of Stuttgart in Germany, sees them as wood’s greatest assets. Menges and his team at the Institute for Computational Design and Construction are uncovering new ways to build with the material by using computational design—which relies on algorithms and data to simulate and predict how wood will behave within a structure long before it is built. He hopes this work will enable architects to create more sustainable and affordable timber buildings by reducing the amount of wood required.

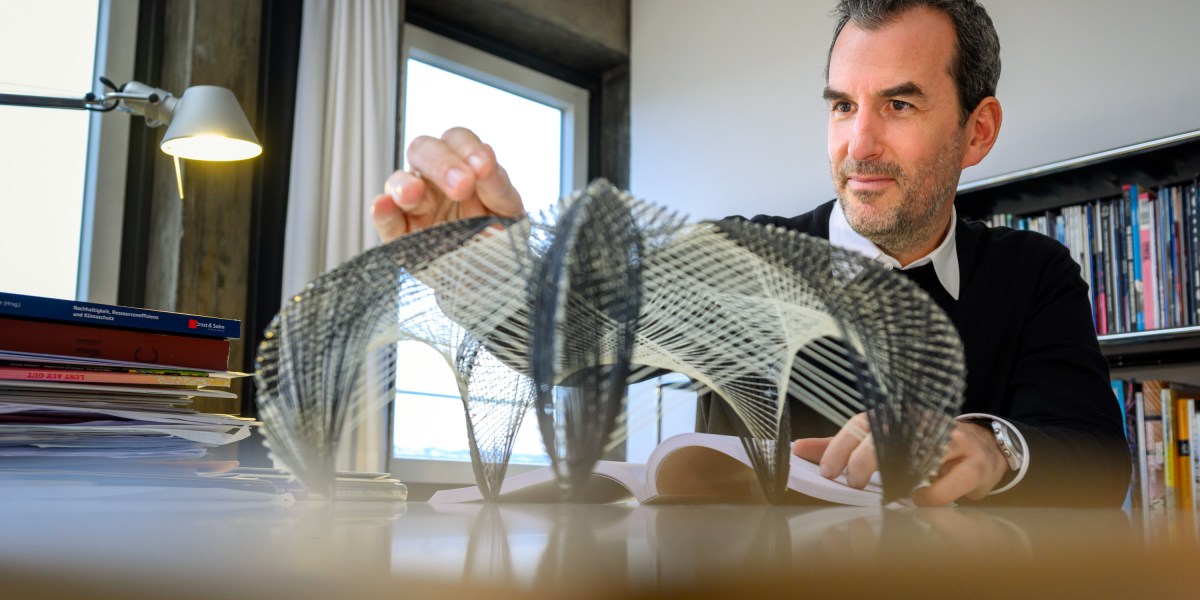

Menges’s recent work has focused on creating “self-shaping” timber structures like the HygroShell, which debuted at the Chicago Architecture Biennial in 2023. Constructed from prefabricated panels of a common building material known as cross-laminated timber, HygroShell morphed over a span of five days, unfurling into a series of interlaced sheets clad with wooden scale-like shingles that stretched to cover the structure as it expanded. Its final form, designed as a proof of concept, is a delicately arched canopy that rises to nearly 33 feet (10 meters) but is only an inch thick. In a time-lapse video, the evolving structure resembles a bird stretching its wings.

HygroShell takes its name from hygroscopicity, a property of wood that causes it to absorb or lose moisture with humidity changes. As the material dries, it contracts and tends to twist and curve. Traditionally, lumber manufacturers have sought to minimize these movements. But through computational design, Menges’s team can predict the changes and structure the material to guide it into the shape they want.

“From the start, I was motivated to understand computation not as something that divides the physical and the digital world but, instead, that deeply connects them.”

Achim Menges, architect and professor, University of Stuttgart in Germany

The result is a predictable and repeatable process that creates tighter curves with less material than what can be attained through traditional construction techniques. Existing curved structures made from cross-laminated timber (also known as mass timber) are limited to custom applications and carry premium prices, Menges says. Self-shaping, in contrast, could offer industrial-scale production of curved mass timber structures for far less cost.

To build HygroShell, the team created digital profiles of hundreds of freshly sawed boards using data about moisture content, grain orientation, and more. Those parameters were fed into modeling software that predicted how the boards were likely to distort as they dried and simulated how to arrange them to achieve the desired structure. Then the team used robotic milling machines to create the joints that held the panels together as the piece unfolded.

“What we’re trying to do is develop design methods that are so sophisticated they meet or match the sophistication of the material we deal with,” Menges says.

Menges views “self-shaping,” as he calls his technique, as a low-energy way of creating complex curved architectures that would otherwise be too difficult to build on most construction sites. Typically, making curves requires extensive machining and a lot more materials, at considerable cost. By letting the wood’s natural properties do the heavy lifting, and using robotic machinery to prefabricate the structures, Menges’s process allows for thin-walled timber construction that saves material and money.