If eyes are windows to the soul, then the eyes in William Stoehr’s paintings convey the isolation and despair that come with addiction and depression. They are lonely and haunting, especially in one of the pieces he painted of his late sister.

Her eyes are dark and sunken. Perhaps she has been crying. In the bottom left corner, Stoehr etched the words: DAD CALLED EMMA OD’d HER SOUL IS AT REST.

Stoehr and his wife, Mary Kay, used to help people find their way with topographical maps. They are the couple who built Trails Illustrated — a company revered by serious hikers, backpackers and outdoor enthusiasts — into a must-have standard. But over the past two decades, Stoehr laid out a second-act career as an artist and self-professed mental health activist, seeking to lead viewers into an empathetic understanding of mental health and the stigma of addiction that inhibits diagnosis, treatment and recovery.

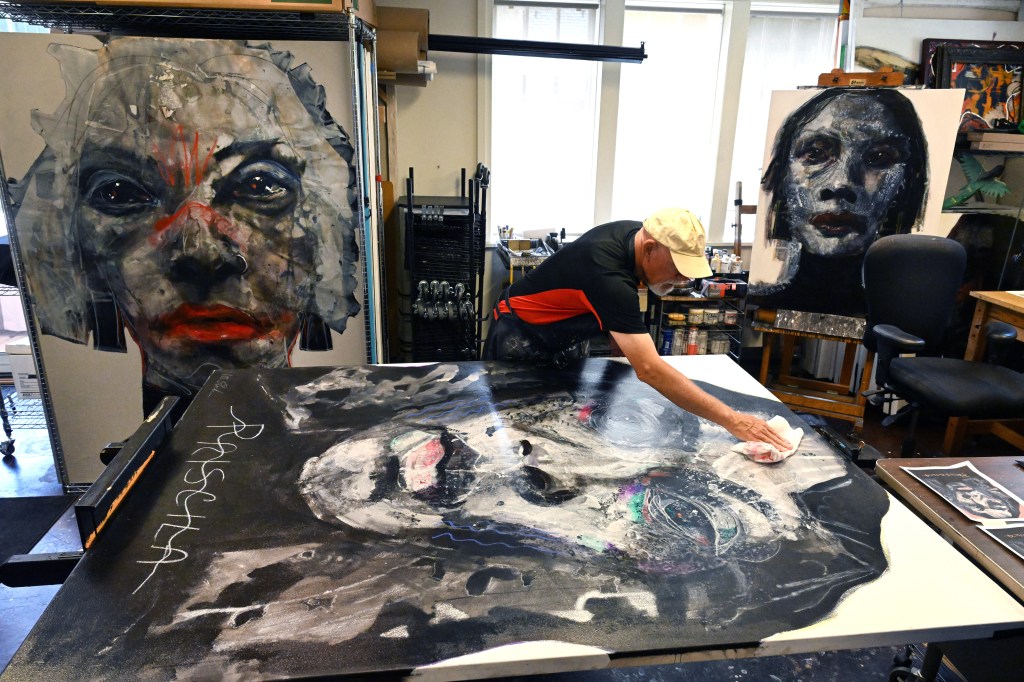

All of his pieces depict abstract faces that fill large canvases, usually measuring 5 feet by 7 feet. He starts with the eyes but says viewers finish the work in their minds, creating what he calls “a greater reality.” He says neuroscience backs that up.

“I put the tools there for you to create the painting,” Stoehr explained in his studio at the couple’s home in Boulder. “You pick up on the part of the face you identify with, and you create the narrative. I lose control of the painting the minute it’s seen by someone else. They reinterpret it, based on how they feel at that moment or what their life experiences are. People stand before my paintings and cry. It’s bringing back some memories deep inside.”

In another painting of Emma (not his sister’s real name), her face is dark black. Barely visible eyes are the only facial features the viewer sees. It’s the painting he promised her he would create if she agreed to go into rehab. She went — her third round of treatment — and was sober for five years until she died from an overdose of prescription pain medication.

“This painting, people just break down and cry,” Stoehr said. “That’s a seven-foot painting, just black spots and two eyes. People say, ‘You captured exactly how I feel,’ or, ‘This is what depression feels like.’”

The Trails Illustrated years

Stoehr, who most people call Bill, and Mary Kay grew up in Wisconsin and met in a lunch line while attending the University of Wisconsin-Stout. She became a teacher and he went into industrial engineering after graduation.

But they had always wanted to live in the West, so they moved to Colorado in 1982. Two years later, Bill severely broke his leg while skiing, leaving him desperate for something physical to do during his recovery. His doctor said he could ride a bike, so they took up mountain biking, which was just becoming a thing. Stoehr discovered there weren’t any good guidebooks for mountain biking on the Front Range, so he wrote two.

Looking to duplicate a map for one of his books in 1985, Stoehr went to see Kaaren Hardenbrook, who owned Trails Illustrated at the time. One bedroom of her Littleton home was devoted to cartography and sales, Stoehr discovered, while the garage was for inventory and shipping. During their meeting, she looked at her watch and abruptly told Stoehr she had to run because she had an appointment with her CPA. She was selling the company.

That evening, on their nightly walk together, Bill told Mary Kay what happened. She slugged him playfully and said, “What are we waiting for? Let’s buy it!”

They owned Trails Illustrated for 10 years. Working with U.S. Geological Survey topographical quad maps, they painstakingly pieced together their own maps on light tables in the basement of their Evergreen home. They met with National Park Service personnel to add informational notes and features that hikers needed. They knew their audience, because they also were avid backpackers.

“We were able to go to USGS in Denver and say, ‘We’re doing a map of Denali National Park. What do you have?’ Mary Kay explained. “They would then reproduce for us photographic negatives. We would buy the base information – the topo lines, the blue which was water, the green which was wooded cover, another layer that was private property, another layer that was roads. Those negatives we would bring back, and on light tables, splice maps to together.”

First-year sales totaled $28,000. From there, they built up the Trails Illustrated inventory and enhanced its brand. In the late 1990s, National Geographic came calling, looking to expand beyond its membership base by entering the for-profit world with books, maps, television and movies.

“They needed somebody to do maps,” Mary Kay said. “They had like 50 cartographers, but nobody knew how to get maps into distribution, because up until that point, (National Geographic) only went to members. They wanted to get into bookstores, map stores, REI, everywhere.”

National Geographic rebranded Trails Illustrated’s look with the magazine’s yellow and black colors, and hired the Stoehrs to run it. Soon they named Bill president of National Geographic maps. Mary Kay left after five years, but Bill remained until he retired in 2004 to pursue the dream he’d had as a teenager: to become an artist.

Becoming an activist artist

Stoehr (pronounced Stare) begins a painting by sketching the eyes, nose, lips and chin on a canvas held vertical on an easel. Then he tips the easel into a horizontal position. He brushes, pours, splashes and dribbles watered-down acrylic paint wherever his spirit moves him. Sometimes he spreads paint with a squeegee.

He also uses paper towels — what he calls his “secret sauce” — to dab and create intricate patterns. “I only use Bounty, because I like the pattern and I’m used to how it absorbs,” said Stoehr, 76. “That’s the first layer. Then I’ll put varnish on it, acrylic varnish. It dries in like 10 minutes. Then I’ll put down another layer and another layer.”

It’s not unlike the color separations that went into printing Trails Illustrated maps. That connection is not lost on Stoehr, although it didn’t occur to him until others pointed it out to him.

“A map is made in layers,” Stoehr said. “They print one color, then another and another — exactly how I paint.”

Over the years, his work has been in more than 120 exhibits and 30 one-person shows. They are part art appreciation, part education about substance-use disorders.

“It’s more than an art show,” Stoehr said. “What I say is, come for the art, stay for the message.”

It only took Stoehr 40 years to find his message and platform. He wanted to go to art school when he was 17 but couldn’t afford it. He became a full-time artist after retiring from Trails Illustrated at age 55 and got his first break from Michael Burnett, the owner of Space Gallery in Denver’s Art District on Santa Fe.

“I walked in with a roll of paintings, spread them out and said, ‘Just give me five minutes. If you want me to stay, I’ll stay. If you want me to go, I’ll go.’ He looked at me and said, ‘Well, I just had someone cancel out of a show and I need an artist.’ So he took me on.”

Burnett later gave him advice that proved pivotal.

“I said, ‘I’m having fun with the painting part of it, but it doesn’t have soul, and it’s not hanging together as a group (of paintings),’” Stoehr said. Burnett replied, “‘Why don’t you start doing big faces? You really do faces well.’ So I started doing big faces, and I haven’t looked back. Shortly thereafter, my sister died of an opioid overdose.”

From her tragic life and death came his mission.

“I was at a point of saying, ‘What good is your art? What are you accomplishing?’ ” Stoehr said. “Suddenly I could be an activist about stigma. I started painting what I called victims, witnesses and survivors. I didn’t consider myself a victim, and I wasn’t a survivor, but I was a witness to my sister. I was very involved in trying to get her into proper care for several years. The thing I could do as a witness was to work on the stigma, because the stigma keeps people from care.”

The tragic death of Emma

Stoehr’s sister got into drinking and drugs while growing up in small-town Wisconsin. She married a man with the same issues, so they became codependent alcoholics and drug users. After she developed back problems that resulted in two failed surgeries, she became addicted to prescription opioids. There were two failed attempts at rehab in residential treatment facilities.

On a last-ditch visit to Wisconsin, Stoehr begged her to go into rehab for the third time, telling her he wasn’t leaving until she agreed. She finally relented but when she called her doctor, who was home with his family on a Sunday, he told her to call back when he was in the office. Then he hung up on her.

“She threw the phone down, started crying, ran to her room and slammed the door,” Stoehr said.

Stoehr pleaded with her to come out. Then he remembered how much she loved his art and wanted him to paint her. He blurted out the words he would later put on one of her portraits, the one where her face is an all-black figure: “I promise to paint your portrait if you promise to go into rehab.”

The door opened and she agreed.

“She was good for five years,” Stoehr said. “She would be good today if she hadn’t had another back surgery and they gave her the opioids.”

She died in 2012. Her death was ruled accidental.

Driving up Boulder Canyon one day to go hiking with Mary Kay, Stoehr got a call on his cellphone from a man who had seen one of Emma’s portraits. He didn’t recognize the number, but took the call and put it on speaker.

“This guy said, ‘Oh my God, I didn’t think I’d get to you.’ He’s crying and he said, ‘My daughter’s name is Emma, she OD’d and died.’ I’m trying to drive, I’m crying, Mary’s crying. It’s brutal.”

Originally Published: