For a guy who always seemed so stiff in front of a camera, whose lack of Hollywood glamour and mystique (especially compared with his predecessor) was such a constant thorn in his side, and who’s been dead for more than a half century, Lyndon B. Johnson has enjoyed a surprisingly durable career in showbiz. LBJ has popped up in scores of plays, movies, TV shows, and even video games, everything from Hey Arnold! to Oppenheimer to Metal Gear Solid. He’s been assayed on stage and screen by some of our finest actors, often wearing our most atrocious makeup. Woody Harrelson, Tom Wilkinson, Bryan Cranston, and Brian Cox—every thespian of a certain vintage and heft, it seems, should have both a Hamlet and an LBJ in their repertoire. Not too shabby for a president who was elected exactly sixty years ago, who served just a single term, and who left the office so unpopular that he was more or less exiled back to Texas to live out his few remaining years. To put it in perspective, all Jimmy Carter ever got was a cameo on Home Improvement.

It seems that no one would have been more pleased by this unexpected cultural immortality than Johnson himself. According to historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, a retired LBJ loved reenacting key moments from his presidency with “full-blown theatrical performances,” where he’d impersonate his erstwhile Cabinet members and political rivals, mimicking their voices and facial expressions. After a full day of working on his memoirs, Goodwin said, he would spend afternoons walking the path of his life as it is laid out on his Johnson City ranch, wending his way from the so-called Texas White House to the reconstruction he’d commissioned of his birthplace home, which sits not far from the school he attended and the original family settlement owned by his grandfather. “He found comfort and relief in moving backward in time from his tumultuous presidency to the early years of his upward climb,” Goodwin wrote, as though Johnson believed that his accomplishments would be amplified—and his failures ameliorated—if he could put them, again and again, in the contextual sweep of his story.

I visited the Johnson ranch once, when I was around eleven years old, while on spring break from school in 1989. My grandparents loaded me, my aunt, and my cousin into a Winnebago to drive us all down to Lyndon B. Johnson National Historical Park, where we took in every artifact and salty anecdote. It was, and remains, the most boring trip I have ever taken in my life. Some of this, clearly, was my fault. Photos from that day reveal a petulant kid in the grip of early onset adolescence, my hands fingering the Walkman I’d much rather have been listening to as I posed begrudgingly next to some cow or dusty old well. But some of this indifference, I maintain, was because LBJ’s story, as told by the park, seemed so dull and prosaic: The hardworking son of the soil turned cowboy president, who bravely wrangled with, and was ultimately undone by, historical forces bigger than himself. For all his supposed color, he seemed mostly like a cipher. Years later, when I attended the University of Texas at Austin, I used to pop by the LBJ Library and watch the animatronic Lyndon Johnson cycle through his prerecorded humorous anecdotes like a cornpone Chuck E. Cheese. Even then, I never would have expected to someday watch a whole movie about the man.

For many years, Hollywood agreed with me. The bulk of Johnson’s screen depictions, much like his presidency, feel almost circumstantial, just a matter of his being in the right place at the right time. Or the wrong time: LBJ, after all, was at the fulcrum of one of the most dramatically rich periods in American history, and you can’t make a credible movie about the Kennedy assassination, the civil rights movement, the space race, the Vietnam War, or the sixties in general without LBJ’s popping in somewhere, even if it’s just for a bit of place-setting archival footage. In a lot of those movies, he was relegated to (as in his life) a glorified cameo. Particularly in films about the Kennedys, such as Thirteen Days, JFK, Parkland, or Jackie, LBJ is mostly there only because verisimilitude demands it. He’s just waiting in the wings—or, if you believe Oliver Stone, the shadows—as the sad-trombone denouement to Camelot.

Like that LBJ bot, Johnson was often reduced to a cartoonish stereotype. He was the blustering cowboy buffoon from The Right Stuff, whacking away at his limousine and yelling, “Gladiolas!” because John Glenn’s wife doesn’t want to have him over for dinner. Or he was the guy who whispers to Tom Hanks in Forrest Gump that he’d like to see his wounded butt-ocks. Even in more recent shows such as The Crown, Johnson, as played by Clancy Brown, crashes the stuffy House of Windsor like he’s Rodney Dangerfield in Caddyshack, reciting dirty limericks and challenging Princess Margaret to a drinking contest. He is often more caricature than character: the impudent, tasteless Texan as the quintessential ugly American, whose DNA lives on in every crass, wheeler-dealer, Southern politician you’ve ever seen on-screen.

Among the first films to make Johnson out to be more than mere comic relief, LBJ: The Early Years, from 1987, was still not especially flattering. Randy Quaid won a Golden Globe for his turn as a young, obnoxious schmoozer LBJ—a hoo-weeing redneck goon who’s not far removed from the one Quaid played in National Lampoon’s Vacation—who hardens into a graying old crank, whimpering into his whiskey that the Kennedys have left him feeling like a “cut dog.” The Early Years was a made-for-TV movie, and it shows through its sanitizing of LBJ’s notorious profanity (saddling Quaid with awkward lines like “That’s a bunch of can’t-do horse manure!”) and in its broad, soap-operatic corniness. Nevertheless, it does rustle up a little pity for Johnson. In one key scene, a senator’s wife derides him as “a nobody from the Hill Country who’ll have tobacco juice on his shirt until the day he dies,” and Quaid lets you see just how much the line sticks in Johnson’s craw, the Rosebud in his Citizen Kane. The film ends as Johnson takes the oath of office in Dallas, however, reducing his entire presidency to a rapid series of crowded title cards that speak to how little the nation at the time ached to relive it.

In recent years, however, there’s been a shift in how—and how often—we think about LBJ. Many historians now rank Johnson as one of the best presidents America has ever had. He is certainly considered to be one of its most consequential, thanks partly to a raft of legislation that continues to influence domestic policy to this day and partly to the way that legislation split and reshaped the Democratic and Republican parties. We seem to take Lyndon Johnson much more seriously in the twenty-first century: In 2012 even that animatronic LBJ got a makeover, his Stetson and gingham shirt replaced by a drab charcoal suit and the whitewashed corral fence he used to lean against swapped for a more dignified podium. The idea was to make him seem more “presidential,” museum officials said, an image that, ironically, LBJ struggled to project in his life—and one that his cultural depictions have long denied him. But in addition to a slow avalanche of biographies, there have also now been several films with Johnson as a main or major character, one who’s suddenly been deemed worthy of earnest consideration and more nuanced portrayal.

What’s behind the rehabilitation of a man America seemed determined to ignore for so many years? Some of it is surely the passage of time, which has helped dull the wounds of the Vietnam War, in particular. Since the nineties, the gradual release of hundreds of hours of secretly recorded White House conversations has afforded us a more intimate understanding of Johnson’s reasoning and fears. Meanwhile, newer wars and fresher quagmires have helped to engender if not sympathy for LBJ then at least a deeper understanding of how history has a way of yoking even the most bullheaded of leaders to its will. It’s no coincidence, for example, that John Frankenheimer’s Path to War premiered on HBO in 2002, in the wake of 9/11, just as another newly minted Texan president found himself dragged into another interminable conflict with another inscrutable enemy.

The LBJ in Path to War, as played by Michael Gambon with a truly tortured Southern accent that barely conceals his Irish brogue, is shown at the beginning of the film in the flush of his sweeping electoral victory in 1964, arrogantly comparing his congressional rivals to cows quivering before a well-endowed bull (a metaphor he illustrates with a bottle of Cutty Sark). But then the film fast-forwards to Vietnam, and Gambon’s Johnson becomes almost an impotent bystander, listening in horror as Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara (played by Alec Baldwin) drones on about battle tactics. The president realizes that all his grand Great Society plans are destined to be overshadowed, then forgotten. Path to War doesn’t beg forgiveness for Johnson, but it does, at least, invite us to understand his predicament and sympathize with what it cost.

Thanks especially to Black filmmakers, we’ve also been able to more fully recognize Johnson’s role in the civil rights movement. Granted, in centering the Black men and women who led that charge, some of these movies have also tended to diminish LBJ’s contributions and even faintly damn the man. In 2013, Lee Daniels’ The Butler gave Johnson, played by Liev Schreiber, a mostly cursory nod. The actor recites a snippet of the president’s “We Shall Overcome” speech and watches the Bloody Sunday attacks while morosely petting his basset hound. But his biggest scene takes place on the toilet, where Schreiber, sweating through his prosthetics, bellows for prune juice while liberally dropping the N-word. Ava DuVernay’s Selma, released in 2014, treats Johnson with relatively more dignity, thanks largely to the British actor Tom Wilkinson and the way he gives LBJ a sort of weary, hangdog grace. Still, the film also earned criticism for the way it treated Johnson as more of an antagonist than a champion of Martin Luther King Jr., enough so that some audiences reportedly hissed whenever he appeared on-screen.

Then again, the truth about LBJ—and the reason he remains so vital as a character—is that he really was all of these things. He was both hero and villain; an idealist and a bully; an orator who was capable of stirring persuasion and a vulgar hick who loved whipping out his penis as a rhetorical flourish. In recent years, especially, it’s become common to call Johnson a Shakespearean figure, something the playwright Barbara Garson picked up in 1966 with her merciless satire MacBird! Johnson is Brutus, Hamlet, King Lear, Macbeth, and Richard III all rolled into one titanically tragic protagonist. He’s a larger-than-life yet cripplingly insecure man who finally attained the power he’d always lusted after in a near-Faustian bargain that ensured he’d never enjoy it completely and whose desire to rule and be loved for it was rapidly undone by his own hubris and the dark vicissitudes of his times. As Robert Caro proves, you could spend more than forty years writing multiple doorstops about this guy and still not even get to the third act.

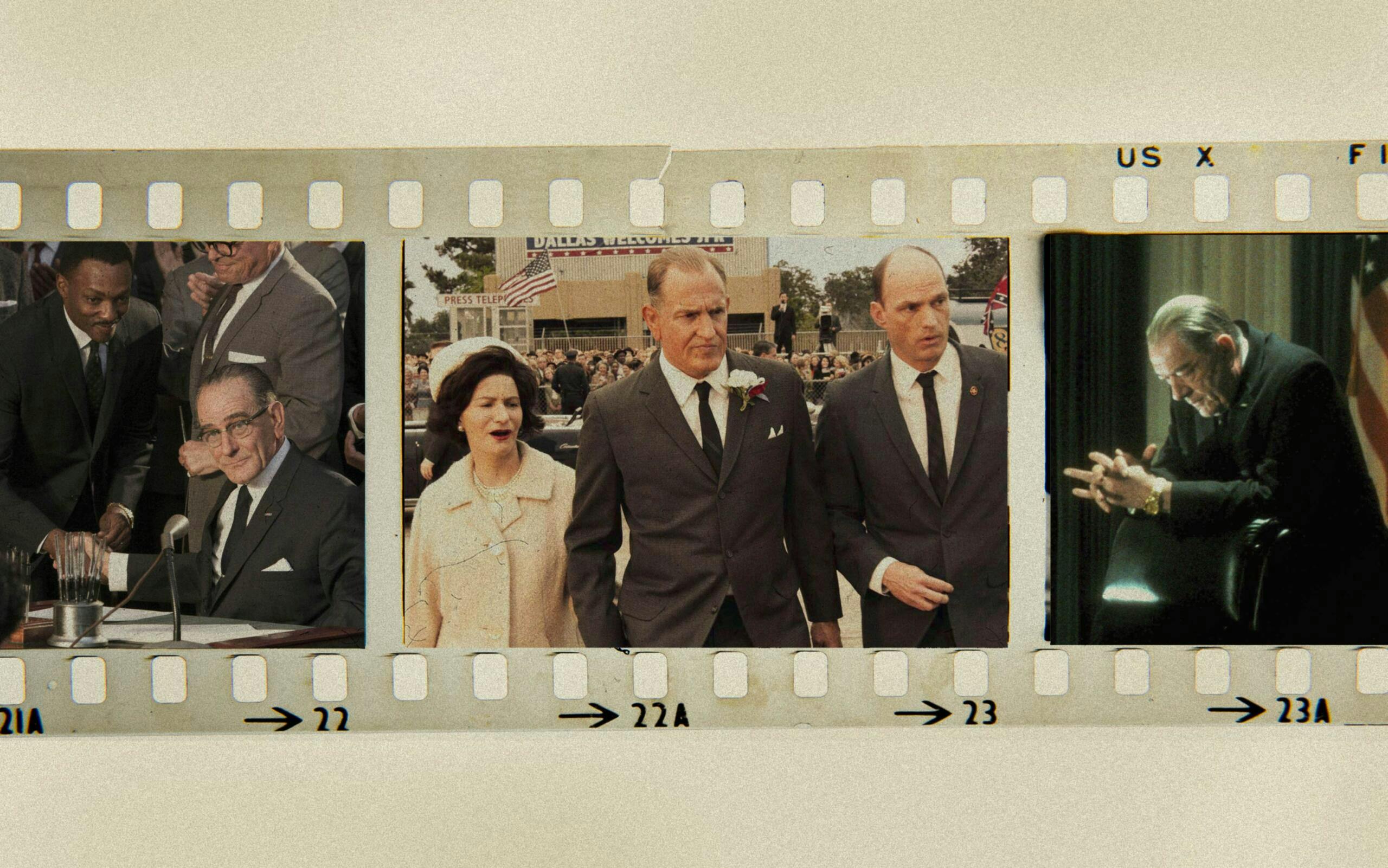

This is why so many modern dramatists keep returning to LBJ—and why nearly all of them still manage to capture only a shadow of the man. The past decade has seen the release of two full-blown biopics of Johnson, dropped right on top of one another: There’s 2016’s All the Way, starring Bryan Cranston in the role he played to some acclaim in Robert Schenkkan’s Broadway hit of the same name, and 2017’s LBJ from director Rob Reiner, with Woody Harrelson doing his damnedest beneath two tons of latex that, in certain lights, makes him look like the dancing old man from those Six Flags commercials. The films overlap in several ways, sharing a timeline that begins in the immediate aftermath of Kennedy’s assassination and ends before the 1964 election, before the Vietnam War fully arrives to ruin everything. And they rehash a lot of the same stories and clichés: the staff meetings on the toilet; Johnson’s infamous call to his tailor, where he requests more room in his pants between his “nutsack” and his “bunghole”; the major awards-baiting speech where LBJ explains his newfound passion for civil rights with an anecdote about his beloved housekeeper being forced to urinate on the side of the road after she’s shut out of whites-only restrooms.

Cranston, aided by some residual malevolence from Breaking Bad, proves a tad more effective at embodying the famed “Johnson treatment” of cajoling, threatening, and physically looming over his political rivals. Harrelson’s LBJ is just a little too stoner-meek (and short) to be as intimidating, although his native Texanness does lend a patient tenacity to Johnson’s gamesmanship, as compared with Cranston’s more theatrical broadsides. But both offer a more complex picture of the man than most seen inside the LBJ Cinematic Universe. Neither shies away from his faults, as he is shown, for example, being casually cruel to Lady Bird—Melissa Leo in All the Way; Jennifer Jason Leigh in LBJ—as well as to his women secretaries, whom he impulsively fires in favor of “girls with a little more meat on their bones.” More than anything, however, these films ask us to feel sorry for Johnson, each of them depicting a man who is left to fret endlessly about his legacy as an “accidental president” and who occasionally even curls up in bed with a big tub of ice cream, Bridget Jones–style, to moan that nobody likes him. “People think I want great power, but what I want is great solace,” Cranston says in All the Way. “A little love. That’s all I want.”

We seem more primed than ever to give it to him, both at the movies and in our larger cultural imagination. When the dual release of All the Way and LBJ inspired Texas Monthly’s Stephen Harrigan to write about 2017’s unexpected bounty of Johnson movies, he suggested that they tapped into our sudden thirst for films that portrayed politicians as competent people at a time when Washington, D.C., seemed especially consumed by instability and chaos. Today, amid the turbulence of another contentious presidential election—in a year when we’ve been urged more than ever to despise our ideological opposites and view them as the enemy within—I think we might also find comfort in these movies’ depictions of politicians as people, period, especially a person who is as empathetically, recognizably flawed as Johnson. He is so messy and quintessentially human, a reminder that politicians are neither the superheroes nor the demons we sometimes make them out to be.

On that tedious trip I once took to Johnson City, my grandfather had seemed so enamored with Lyndon Johnson that—although I’d always known him to be a staunch Republican, a guy who adored Ronald Reagan and quoted Rush Limbaugh like it was gospel—I assumed that he must have voted for LBJ way back when. It was only long after my grandfather died that my dad told me there was no way in hell—he’d had been all in for Barry Goldwater. My grandfather was a good and decent man, but he was also an inveterate racist who’d been raised in the Jim Crow–era Deep South, and he just couldn’t abide by Johnson’s policies on civil rights. Still, he’d found reasons to like LBJ anyway. I could easily picture the two of them strolling Johnson’s ranch, my grandfather unfurling his deep, throaty chuckle at one of his host’s dirty jokes. I believe they’d have been fast friends just so long as they avoided politics, the way I’ve learned to do over many Thanksgivings.

I fear that we’ve lost some of that nuance and compassion in our understanding of one another. Depending on your point of view, Johnson may be a good man who did terrible things or a terrible man who managed to accomplish some lasting good. But really, he was both—all of our noblest intentions and worst impulses contained in one bold, petty, generous, manipulative, righteous, calculating, and childish man, straddling the divide between the past we are always trying to outrun and the future we’re forever straining to reach. In many ways, Lyndon B. Johnson was America, more so than John F. Kennedy ever was—and while that is a compliment to neither him nor us, it’s also the truth. LBJ was the best and the worst of us, and this continues to be a compelling story. It’s no wonder we keep trying to tell it.