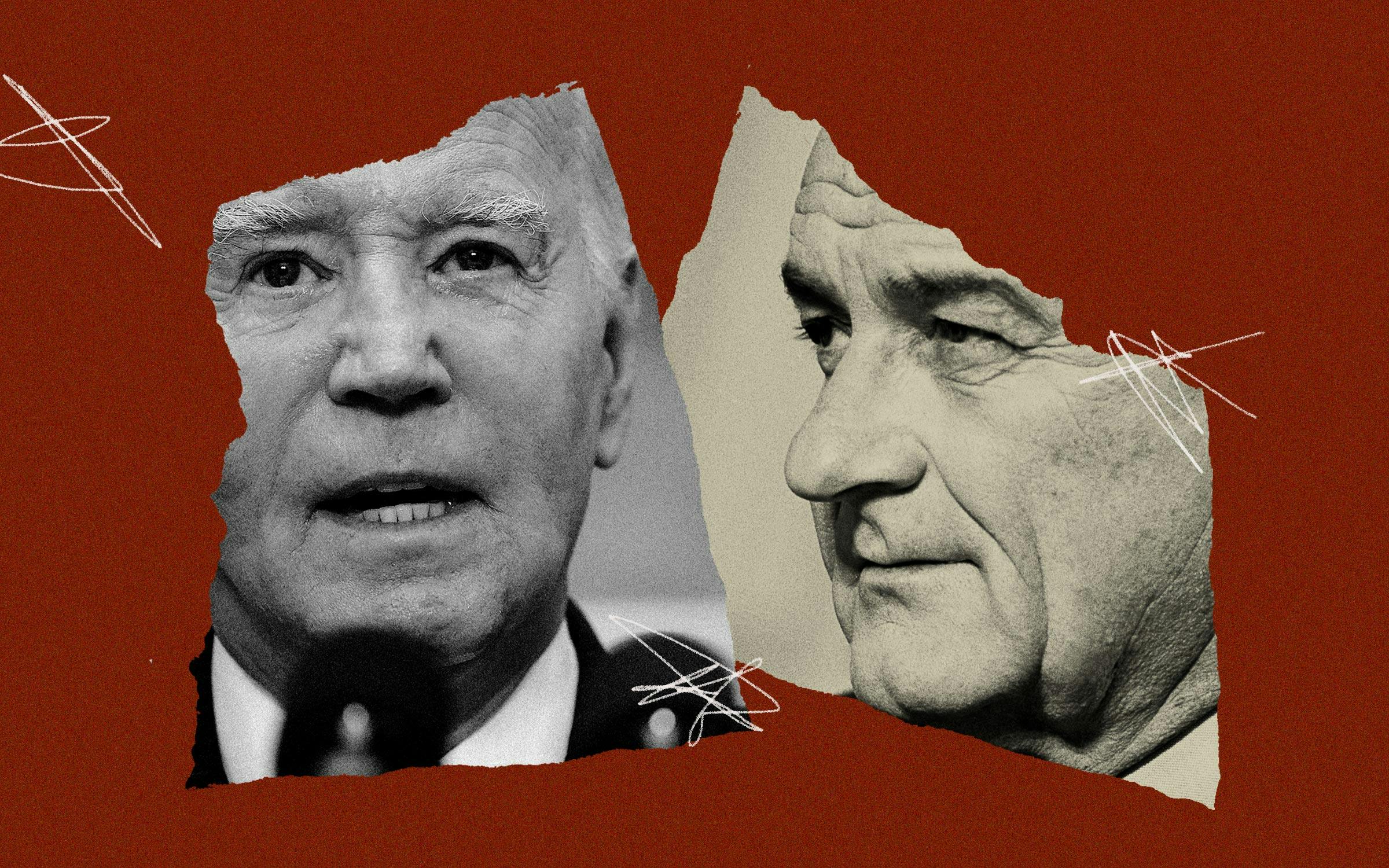

Sixty years ago today, President Lyndon Baines Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act, a high point in one of the greatest runs of policymaking of any president in American history. The Johnson administration was sprinting for most of the president’s years in office, and as he approached the end of his first full term a few years later, he was exhausted and unhappy. In 1967, when Johnson was just 58 years old, he commissioned a secret actuarial study to try to determine how much longer he should expect to live. His father died at just 60, and Lyndon had had a heart attack in 1955. The study suggested he should expect to expire at 64. “I figured that with my history of heart trouble I’d never live through another four years,” he told Leo Janos, a former aide, in 1971. “The American people had enough of presidents dying in office.”

Johnson’s predecessor had died in office, of course, in a maximally traumatic way. But, as he told another aide in 1967—George Christian, who wrote about Johnson’s decision to retire in 1988 for Texas Monthly—he was more worried about drifting into infirmity than dying. Woodrow Wilson was barely able to function in the later years of his presidency; same with Franklin Roosevelt, who died less than three months into his fourth term. The consequences of those periods of illness at the ends of two world wars—the men who rose in their wakes, the decisions not made—shaped the twentieth century.

As time went on, Johnson gained more reasons to consider retirement. His approval ratings were tanking because of the Vietnam War, at times hovering below 40 percent. He underperformed in primaries versus protest candidate Eugene McCarthy, a Minnesota senator. It began to look like he would either lose the nomination—to Senator Robert F. Kennedy, with whom he shared a deep mutual loathing—or lose the general election to Richard Nixon. The country was tired and mistrustful of him. He’d used up his political capital. He thought he had a shot at ending the war through negotiation—one that would be strengthened if he no longer had to campaign. So on March 31, 1968, Johnson pulled the trigger. “I shall not seek, and will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your president,” he told the nation in a televised address. It was a shock to the country.

Johnson was as facile with power, and as eager to wield it, as any politician in American history. It was his lifelong identity, central to his being. You might expect that the end of his tenure would crush him, that he was slinking home in defeat. But his aides remember his almost childlike glee that night. He had done his part. “Johnson was as happy that night as I ever saw him,” wrote Christian in Texas Monthly. “The burden was off, and he was like a young boy.”

Counterfactuals are never certain, but Johnson’s desire to step down was ultimately helpful to his legacy. Had he lost to Nixon, it would have been seen as an even starker rejection of his domestic program, and he would have gone home in defeat. Had he won another term, it is hard to imagine it going well. As it was, vice president Hubert Humphrey lost and took the blame for Nixon’s victory, which looks preordained in hindsight. Johnson went home on his terms. He returned to the ranch and lived hard for four more years, applying the same vigor to the management of his land and cattle as he had applied to the passage of the Civil Rights Act. He had good days and bad days, but he spent them with his family. He chain-smoked and drank too much and tried hard to make the actuary’s prediction come true. He succeeded, dying at 64. The country never quite reconciled itself to his presidency while he lived, but he has been creeping up historians’ lists of the greatest presidents ever since.

History doesn’t repeat, but it rhymes. In 2024, a Democrat is in the White House. He became president at a moment of national crisis and has had a productive run with Congress, given the circumstances. He’s done much that his party is proud of. But there are serious warning signs. The president’s poll numbers are abysmal, and he seems likely to lose the general election. A war that the U.S. is intimately involved in is causing divisions in the Democratic coalition, and he is sliding toward a Democratic convention—in Chicago, no less—propelled more by inertia than by any kind of positive vision for the country. He faces a Republican in the general election who has run for president before, is seeking revenge on those who have spurned him in the past, and evinces authoritarian tendencies. And he faces concerns about his health. (It is remarkable to think that if Lyndon Johnson first became president at the same age Joe Biden did, he would have assumed office in 1987.)

Following the president’s disastrous performance in last week’s debate—in which he mumbled downheartedly for an hour and a half, pledging to “beat Medicare” and bizarrely invoking the right-wing talking point of immigrant violence when asked about abortion laws—Democrats are divided into two camps. Those in the first think that any supposition that Biden isn’t up to the task is harmful, and that it helps Trump. They ask the 72 percent of voters who say Biden is mentally unfit to serve: Who are you going to believe, me or your lying eyes?

The second camp—which includes virtually the entirety of the liberal media, speaking with a rare unified voice—thinks the party is sleepwalking toward disaster. Another candidate might have a chance, they suppose, but this one no longer does. They were joined on Tuesday by Congressman Lloyd Doggett, of Austin, the first House Democrat to call on Biden to resign, noting Johnson’s example in his statement.

But while the two sides are arguing, the decision that needs to be made is Biden’s alone, and human nature being what it is, it won’t be made with a clear and impartial sense of the national interest, because Biden is a motivated party. Biden will arrive at a decision with his sense of legacy and reputation in mind—in coarser terms, his ego. In that case, Biden could learn from Johnson’s example. LBJ’s legacy was bolstered by his final act. If Biden loses a landslide election to Donald Trump after a race in which he was unable to give his all, he will not be remembered so fondly by his party.

Johnson’s decision to withdraw from the race in 1968 stemmed from his extraordinary command of self and his unrelenting honesty. He knew his mind better than any of his advisers did. When he started making plans to step down in 1967, Christian wrote, Christian thought the boss was just in a bad mood. But the boss was serious, and the boss ran the show.

The picture of the Biden administration that’s emerging is different. Biden has been visibly in decline for a long time. He has been propped up by loyal advisers and a loyal family, which may work well in the context of a presidency but doesn’t work at all on the campaign trail. He does not appear to have been capable of the same kind of self-searching honesty Johnson was, and it’s hard to blame him: it’s surely hard to face one’s decline. But neither does he have anyone around him, if the flood of postdebate reporting is to be believed, who can supply the honesty he needs.

There may be a generational difference here, too. The late Supreme Court justice John Paul Stevens, whose birth year was closer to Johnson’s than Biden’s, held his seat for nearly 35 years and announced his retirement at the age of 89. He remained sharp to the end. But when he lost confidence in his ability, he almost immediately made plans to leave.

These days, political figures seem to prefer to work themselves to death. Both parties are gerontocracies, but the Democratic Party is more afflicted. Senator Dianne Feinstein hadn’t been cognitively sound for years when she died in office, at ninety. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg helped erase her legacy by declining to retire when a like-minded successor could be chosen, even though she’d already suffered from multiple kinds of cancer. There’s a widespread failure in the party to not only call it when the day’s work is done but also plan for the aftermath.

All who hold great power think themselves indispensable. Johnson has been mythologized over the years on the basis of his indispensability—he was an extraordinary political talent, adept at manipulating Congress, farsighted in his vision. But no politician is indispensable. Johnson understood power well enough to know when to relinquish it. His party may have forgotten that, for a while, but Biden has a chance to teach them.