Growing up on the South Side of Laredo, the Lozano kids were taught that the path to a better life was through education. So when Jessica Lozano saw her younger sister Jennifer singularly focused on the sport of boxing, insisting over and over that she was going to fight in the Olympics one day, Jessica tried to be supportive—but also acted as a voice of reason.

“We told her, ‘That’s great; as your family, we believe in you—but maybe take a few college courses on the side,’ ” Jessica recalled. “We were like, ‘Jenny, we just want you to have a Plan B.’ And I remember vividly when she said, ‘You know I love you. But there’s no Plan B for me.’ ”

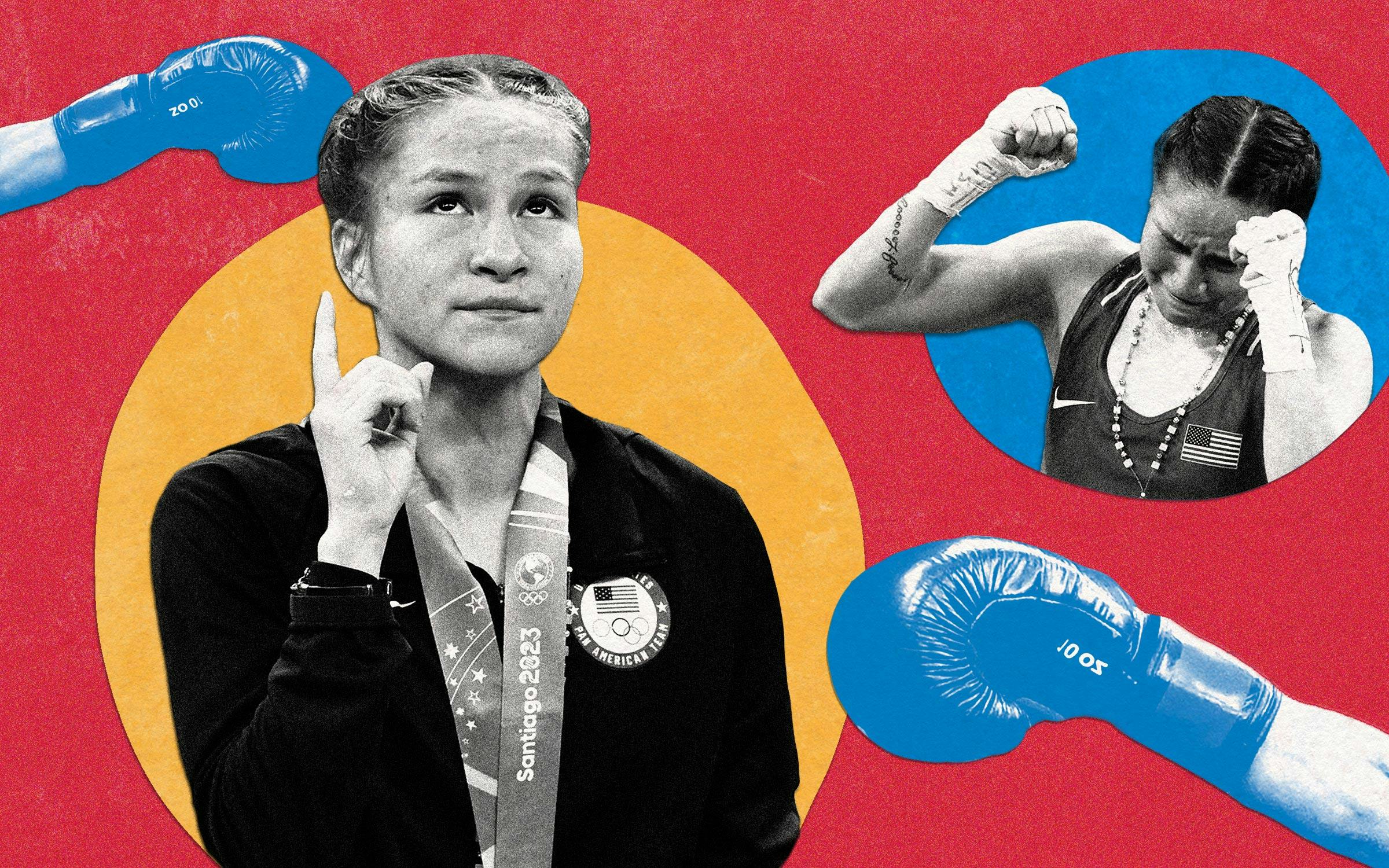

Last October in Santiago, Chile, Jennifer Lozano defeated Canada’s Mckenzie Wright by unanimous decision to ensure a top two finish at the Pan American Games and punch a ticket to the Paris Olympics. When she competes in her first bout of the women’s flyweight (50 kg, or 110 pounds) tournament—she faces Finland’s Pihla Kaijo-ova on Thursday, in the round of sixteen—she’ll become the first Olympian in any sport to hail from the Rio Grande Valley border city of Laredo.

So far, Plan A is working just fine for the 21-year-old Lozano.

The people of Laredo have embraced having an Olympian in their midst. When Lozano landed at Laredo International Airport on October 29 after her triumph in Chile, she came down the escalator to a crowd of hundreds that included her former high school principal, the school marching band, the county sheriff, and Laredo mayor Victor Trevino. There and then, the boxer learned that October 29 would be recognized locally as Jennifer “la Traviesa” Lozano Day.

That nickname means “the Troublemaker,” and it was bestowed upon her by her late maternal grandmother, who spent countless afternoons watching her when young Jenny’s parents were working. As Jennifer’s mother, Yadhira Rodriguez, explained, her youngest child was only a troublemaker at home and with family, where she felt safe and comfortable wreaking a little havoc. Elsewhere, she was a well-behaved kid.

It was the other kids in the neighborhood who were making trouble—trouble that led Lozano into boxing.

During her elementary school years, Lozano was overweight and frequently bullied, getting jumped repeatedly on her walk home from class. There was a boxing gym near where she lived, so when she was ten years old, determined both to lose weight and to learn to defend herself, Lozano stepped through the gym’s doors.

She took to the sport immediately, and she wanted to do more than just hit bags and jump rope. Lozano wanted to compete. But the coaches there denied her. In a recent interview with Olympics.com, Lozano recalled that they wouldn’t let girls take part in amateur matches—especially not a girl who was still overweight. “That shattered me. It broke me,” Lozano said. “But my mom saw something in me that I didn’t see in myself at the time.”

Rodriguez looked for another gym that would allow her daughter to participate in amateur tournaments, and she found Eddie Vela’s Boxing Pride Fitness in north Laredo. Rodriguez and her family (she and her husband, Ruben Lozano, were in the process of getting divorced around this time) lived on the South Side, and Rodriguez worked near Vela’s gym, so at the end of her shift, she would make the 35-minute drive home, pick up Jennifer, drive back across town for those same 35 minutes, wait at the gym until her daughter finished training—sometimes as late as 10 p.m.—and then make the drive back home.

But Rodriguez didn’t hesitate because she saw Jennifer’s commitment. “I was like, oh my God, my girl is really in love with this sport,” Rodriguez said.

And she’d found the right coach. “I remember her walking in with her mom, wearing long basketball shorts, a muscle shirt,” Vela told Texas Monthly. “She had long hair, kind of tough-looking. I put her in a class that is not a competition class, but she wanted to compete. So, within a month or so, I moved her up to the fighting team, and she was boxing against boys, and I just remember her putting it on them.

“The will to win, the determination she had, her work ethic was like no other,” Vela continued. “Within a few months I started taking her with me out of town for sparring, and before you know it, she was competing in the local events around Texas.”

Lozano’s name and amateur results started appearing in the sports pages of the local newspapers. It didn’t take long for the bullying to stop. “She got that respect that she needed to,” her mom said.

Rodriguez admits “it’s still very hard” to watch her daughter exchange punches in the ring, but she’s gradually gotten better at dealing with that parenting challenge. “ I see her as not a little girl anymore,” Rodriguez said. “I learned how to secure my emotions, because if I was nervous, I thought it could affect her and make her nervous, too. So I tried to be more confident in her.”

It was impossible, however, to fully calm those nerves last October in Chile. Rodriguez made the trip to the Pan Am Games with her daughter, and the anxious mom sweated out a pair of split decision wins before Lozano walked to the ring for a make-or-break bout against Wright. La Traviesa’s jabs and combinations were on point and she won each of the first two rounds on four of the five ringside judges’ scorecards. Given her advantage on the cards, Lozano might have been wise to play it safe in the third-and-final round by avoiding any dangerous exchanges with her opponent, but the Laredo fighter remained just as aggressive as she’d been over the first two rounds.

Those late flurries of punches helped Lozano seal the decision victory, and after her hand was raised in victory, she hoisted an oversized ticket to symbolize that she’d qualified for the Olympics, win or lose in the Pan Am finals. (She ultimately settled for silver in the tournament, losing to Brazil’s Caroline Barbosa de Almeida.) Tears rolled down Lozano’s cheeks as she held that ticket in the ring.

And the tears kept flowing as she made her way to her mom in the stands. “We both were crying like crazy,” Rodriguez recalled. “All the emotions were there. I felt very proud of her. Not just because she won, but because of the person that she is—and that after all of her hard work, that was the result.”

Traveling to Paris is not cheap, but with the help of a GoFundMe that raised $6,500, Lozano’s parents, sister, and a few other family members will be there when she steps into the ring for the single-elimination tournament that begins Sunday.

Lozano’s longtime coach, Vela, will not be giving her instructions between rounds, as Olympic boxers have to temporarily jettison their personal coaches in favor of the USA Boxing team coach. But Vela will be in Paris watching his protégé make Laredo history. And he insists, “She’s gonna feel me right there in the corner.” Vela predicted Lozano is “coming back with that gold,” although insiders don’t consider her one of the medal favorites at flyweight.

Whatever happens, Vela believes her greatest success will come after the Olympics. In amateur boxing, with only three rounds to work with and knockouts a rarity, the emphasis is on “scoring points”—landing clean punches that the judges will notice rather than landing with power. Pro boxing is different. In the professional realm, power is important, as is pleasing the fans.

Lozano plans to turn pro shortly after the Olympics, and Vela is certain her fighting style is better suited to the pro game. “We adjusted a little bit to make her style more of an Olympic style,” Vela said, “but she can’t wait to get to the pros. I’ll tell you, she’s going to shine. More than anything, she’s an entertainer. She has a lot of heart, a lot of guts, and she likes to put on a show.”

But the pros can wait for a while—a fortnight, at least. Laredo’s first Olympian recognizes the importance of the opportunity in front of her. Before Lozano had clinched her berth in Paris, NBC Sports asked her what being the first Olympic athlete from her hometown of about 250,000 people would mean to her. “That means everything . . . everything,” she said. “To show some little girl from a town that’s not even on the map, this small city, with a small population, where it’s so negative, and where even if you move to the next city, people expect you to come back and not make it far because nobody ever makes it out of Laredo . . . to be able to say, ‘Look at me.’ I’m living proof that the impossible is possible.”

She still lives in Laredo, but boxing has already taken her far beyond the city limits, to Chile and now to Paris. Not bad for a young woman who, since the day she fell in love with boxing, has had no Plan B.

Thanks to Lozano, Laredo now has it first Olympian. By the time Jennifer “la Traviesa” Lozano Day rolls around next October, maybe the city will be celebrating its first Olympic gold medalist.