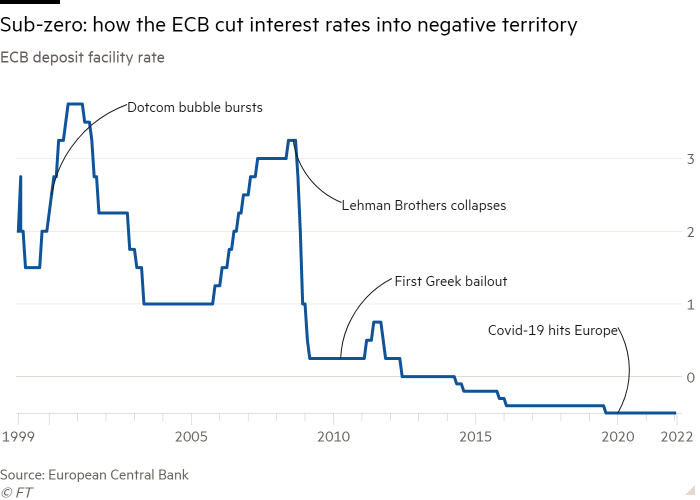

When Christine Lagarde on Thursday sets out the European Central Bank’s plans to end eight years of bond-buying and negative interest rates, she can count on the support of the vast majority of her fellow rate-setters.

Record-high inflation in the eurozone has left even the most dovish of the 25 members of the governing council supporting the need for higher borrowing costs in the coming months.

However, the president will be aware of the scale of the challenge facing the ECB, hoping to regain control of prices without tipping the economy into recession or triggering a bond market panic in the more vulnerable countries of southern Europe.

“Lagarde is in the hot seat and she is feeling it,” said Klaus Adam, an economics professor at the University of Mannheim who advises Germany’s finance ministry. “The ECB seems to think it can bring inflation back to target with relatively timid increases in rates. But what if that doesn’t work?”

The last time the bank raised rates in 2011, none of its 25 governing council members had joined the rate-setting body and Lagarde had just become president of the IMF.

Concerns abound among economists that the council lacks the economics expertise to get the balance right between fighting inflation and avoiding an economic and financial meltdown.

Lagarde, a lawyer by training and France’s finance minister before making the switch to Washington, has relied on ECB chief economist Philip Lane for guidance. But he has been criticised for being too slow to predict the recent surge in inflation, which shot above 8 per cent in May, quadruple the ECB’s target.

Other western central banks, such as the US Federal Reserve and Bank of England, have already raised rates and stopped buying bonds. “Who can she rely on now?” said Adam. “She is no expert herself and her chief economist has been so wrong on inflation.”

While the council members, meeting in Amsterdam for a change from Frankfurt this week, are in unison on the need for rate raises — and to commit to a backstop for bond markets — there is less consensus on the pace of tightening.

Lagarde and Lane have signalled rate rises of a quarter of a percentage point as the benchmark for its meetings in July and September — the two that follow the June decision.

But the pace at which price pressures have intensified over recent months has left hawks calling for a more aggressive pace of tightening, in line with the Fed’s strategy of hiking by 50 basis points at a time.

“The hawks smell blood,” said a more dovish council member.

Most economists still think the ECB is likely to stick to a quarter-point rate rise in July, partly because of the worry that a more aggressive move could trigger a sell-off in the bond markets of heavily indebted countries, such as Italy.

Paul Hollingsworth, chief European economist at BNP Paribas, said a 50-basis point rate rise “would be a hawkish surprise and could increase risks for peripheral bond markets earlier than the ECB would like”.

The spread between Italy’s 10-year borrowing costs and those of Germany, a key measure of perceived financial risk in the euro area, has recently risen to its highest level since the start of the pandemic.

“Some investors are fretting about where spreads could go once the ECB starts to remove its stimulus,” said Annalisa Piazza, fixed-income analyst at MFS Investment Management.

The ECB has already said it expects to raise the rate at which it lends to many banks by half a percentage point this month. It will end the special discount rate of minus 1 per cent on three-year loans made under its quarterly targeted longer term refinancing operations, or TLTROs. This rate will return to the deposit rate of minus 0.5 per cent.

Oliver Rakau, an economist at Oxford Economics, said the TLTRO change could make the ECB reluctant to compound the impact by also raising its deposit rate by half a percentage point in July. “We are already seeing a tightening of bank lending conditions in the eurozone and [the ECB] would risk a steeper tightening than they can stomach, particularly in weaker countries,” he said.

At this week’s meeting, the ECB will also issue new forecasts. They are expected to outline slower growth and higher inflation over the next three years. Its 2024 forecast for inflation is likely to rise to its 2 per cent target — fulfilling a key criteria to raise rates.

For now business surveys, as well as data on exports, industrial production and retail sales, indicate the eurozone is heading for a slowdown rather than a recession this year.

However, the bloc is being hit particularly hard by the fallout from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which has sent European energy and food prices soaring, crimping the spending power of consumers whose wages have risen more slowly.

Goldman Sachs economist Sven Jari Stehn warned that if the war deepens and Russian gas supplies to Europe are cut off, it could plunge the region into a “short, but sharp, recession”.

This stagflation scenario of a shrinking economy with persistently high inflation is one that worries many rate-setters. “It is not going to be easy for the ECB,” said Hollingsworth. “There are a number of hurdles for them to overcome.”