Standing outside the Los Angeles Sentinel offices last week, Black faith leaders from South L.A. and U.S. Rep. James Clyburn (D-S.C.) took turns proclaiming their support for Rep. Karen Bass in her run for mayor.

“The faith community will mobilize around her. We will come full force in pushing souls to the polls,” the Rev. K.W. Tulloss said before quickly correcting himself and adding, to some laughter, ”Souls to the mailbox. We understand what’s at stake.”

This revision may have spoiled the poetry of Tulloss’ appeal, but it hammered home a point that Bass and other candidates will be making this week: Voting is already upon us.

Ballots are now in the mail to every registered voter and can soon be submitted at drop boxes across the city or sent back by mail.

“The election ends June 7,” Bass said. “So our work begins now to communicate with voters and to make sure that voters turn those ballots in. You don’t even have to go out to vote anymore. You can vote from home.”

It remains to be seen, of course, how many voters will participate, and whom they will support. But with a month to go, the race looks far different than it appeared at the beginning of 2022.

At that time, many saw the race as Bass’ to lose. Now, she and a slew of other candidates have to contend with billionaire developer Rick Caruso, who has poured $25 million — four times more than all his competitors combined — into a self-funded pursuit of a position he’s flirted with for years.

Newsletter

Get the lowdown on L.A. politics

In this pivotal election year, we’ll break down the ballot and tell you why it matters in our L.A. on the Record newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Recent polling from the UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies and The Times shows Bass and Caruso statistically tied with others far behind; notably, nearly four in 10 likely voters said they were undecided. Unless one candidate wins more than 50% of the primary vote, the top two finishers will square off in November’s general election.

This mayoral race is unprecedented in several respects: Money has flowed like never before. The new mail-in ballot system, instituted during the pandemic, could drastically increase turnout. This will also be the first mayoral primary in more than a century held in an even year to coincide with state and national elections, which could also boost turnout.

Whether anyone can challenge the frontrunners is unclear. A late surge is the hope for candidates such as City Council members Joe Buscaino and Kevin de León, City Atty. Mike Feuer and activist upstart Gina Viola, who all are polling in single digits.

Nearly all of the candidates are Democrats and this primary is ostensibly nonpartisan, but the attacks on Caruso have taken a decidedly partisan turn and will likely ratchet up as the race enters its final few weeks.

One campaign consultant pointed to 2005, when internal polling showed state Sen. Bob Hertzberg (D-Van Nuys) in single digits eight weeks before the election. A week from election day, after Hertzberg aired ads, Times polling showed him in second and he just missed the runoff, coming in third behind James Hahn and Antonio Villaraigosa with nearly 22% of the vote.

But Caruso has been virtually alone on the airwaves in English, Spanish and Korean since entering the race in February, blanketing television, radio and social media with a simple message: “I’m running for mayor, because I love L.A. Starting Day 1, we’re going to get it cleaned up. … And we’re going to do it together.”

That pitch has been supercharged by the roughly $18 million that he likely will have spent by mid-May. It went all but unrebutted until late April, when Feuer and Buscaino put their own ads on TV.

Trying to offset Caruso’s bulging coffers, Feuer, Buscaino, Bass and De León have been a traveling band of sorts, going together from one in-person forum or Zoom town hall to the next reeling off stats and well-practiced lines about what they’ll do to fix the city’s ills.

Caruso has avoided these events — focusing more on private sessions with business and community leaders along with the omnipresent advertisements. His overall messaging has been disciplined, focusing almost exclusively on crime and homelessness. At times, he has spoken in hyperbolic terms about crime and how unsafe the city appears to be, but his rhetoric has resonated with voters.

“What Rick is doing in a savvy way is tapping into a lot of the concerns and fears that people have about public safety in Los Angeles right now,” said Jeremy Oberstein, a political consultant who until earlier this year served as Controller Ron Galperin’s chief of staff.

“I was having conversations with folks over the weekend in the western part of the [San Fernando] Valley and there’s a lot of concern about public safety. There’s a lot of concern about, going to parks and going to malls and even walking home or walking into your house from your car.”

In the only two televised debates featuring Caruso, his rivals have attacked his wealth, his work as a developer, and the fact that he used to be a Republican.

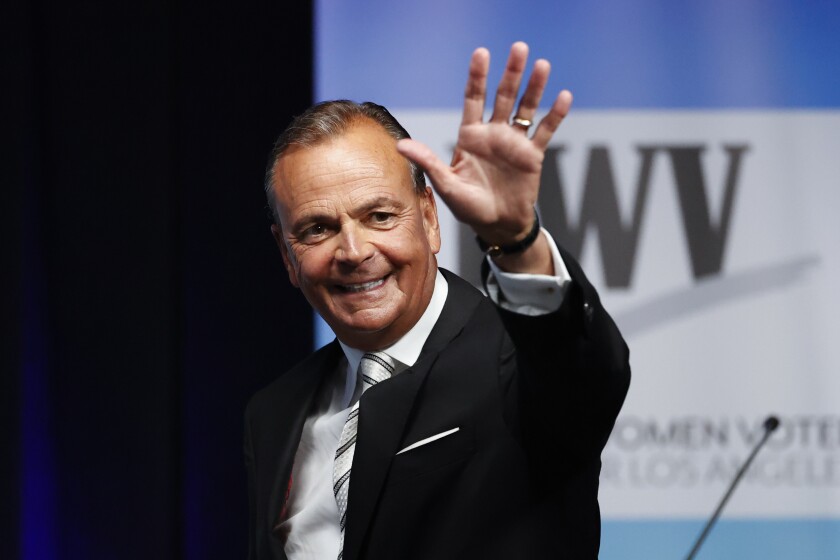

Rick Caruso waves at the start of last week’s mayoral debate at Cal State Los Angeles.

(Ringo Chiu/For The Times)

Still, homelessness and crime continue to tower over any other issues. The two front-runners present starkly different ways of addressing them.

Caruso, a former Police Commission president who regularly touts that work in ads, says he wants to hire 1,500 new officers to police the streets. Bass, who first came to prominence starting a community nonprofit in South L.A. and criticizing police misconduct, wants to move 250 LAPD officers out of desk jobs and into patrols, while ensuring that the department returns to its authorized strength of 9,700 officers. (It had 9,375 sworn personnel as of late April.) She also has said she wants the department to hire more detectives and investigators, noting that the LAPD solved just over half of the city’s murders in 2020.

On homelessness, Caruso has castigated the bureaucratic system and elected leaders who he says have done little to address the crisis. He emphasizes his management experience and a desire to quickly add 30,000 housing units, many of them shelter beds.

Bass, too, wants to expand the number of beds for homeless people — by 15,000 — and like Caruso recognizes the need for laws to govern where people can and cannot pitch a tent, though she’s expressed some discomfort with the city’s current approach. She promotes her work helping foster children, arguing that she would be able to leverage her experience and connections at the state and federal levels to bring more aid to the city.

Buscaino has pushed a pro-enforcement agenda to get homeless people off the streets along with adding more beds. Feuer says adding roughly 3,000 new beds per year in his first term to provide shelter for everyone is realistic.

De León has pushed for the city to build 25,000 units of interim and permanent housing by 2025. He has also been on a well-publicized quest to clear encampments in his district and get people into various forms of shelter and housing.

But these ambitious promises don’t necessarily jibe with the fact that most homeless people do not want to live in group shelters, according to Rand Corp. research published last week.

As the race has heated up, overcoming Caruso and Bass’ advantages has been a slog for the other eight hopefuls on the ballot.

“The other candidates have really struggled to distinguish themselves,” said Sara Sadhwani, an assistant professor of politics at Pomona College. “They each have their own impressive resumes, and accomplishments behind them. But campaigns are about communicating with people that don’t already know you, and that’s the challenge that they have in front of them.”

Over the next month, candidates will need to get their names out through a mix of advertising, events and canvassing. Bass recently opened a campaign headquarters and is having volunteers make calls for her and knock on doors. De León and Feuer have traveled around the city to meet voters.

Caruso poured an additional $2.5 million into his campaign last week, and his broadcast and social media blitz shows no signs of slowing. The other candidates all benefited from the city’s generous public finance campaign matching scheme.

The result is that Bass has nearly $3 million, which she must spend before primary day or else give the money back to donors. The airwaves will also likely be filled with messages going after her as well. An independent expenditure committee funded to the tune of $2 million by the LAPD’s rank-and-file officers union is slated to spend most of that money on ads attacking Bass.

Caruso will also be in the crosshairs. A separate independent expenditure committee supporting Bass has raised just under $1 million, and released its first ad last week attacking his views on abortion and ties to Republicans.

Caruso became a Democrat this year but left the Republican party about a decade ago. Last week, he said he was “pro-choice,” and that he profoundly disagreed with the draft decision overturning Roe vs. Wade. Everyone running, including Bass, issued statements affirming their support for abortion rights and lambasted the draft ruling.

All the candidates have stressed that they have the vision and the skills to bring the city together and right its wrongs. It will soon be up to the voters to decide.

“L.A. is at a crossroads,” Bass said last week at the event with the faith leaders. “Which way are we going to go?”

Times staff writer Julia Wick contributed to this report.