The defendant talked about her struggle overcoming anger and accepting her need for mental health treatment.

When she was done, the judge led the courtroom in applause. Then, further undoing the hierarchy of courtroom decorum, Judge Theresa R. McGonigle stepped down from the bench, wrapped the defendant in a hug and posed with her for photos.

Five times that day, McGonigle and two of her fellow judges repeated that ritual, offering personal salutes to accused lawbreakers who had chosen to go through treatment for their mental illness rather than face prosecution.

The defendant appears before Judge Maria Lucy Armendariz with his public defender, Caroline Goodson in Dept. 48, Clara Shortridge Foltz Criminal Justice Center, Los Angeles, CA.

(Irfan Khan/Los Angeles Times)

After completing their court-ordered mental health programs, each had walked out of the courtroom free — charges dismissed and criminal case expunged from the record.

Even the prosecutor was complimentary.

“It was a pretty harrowing incident that took place,” Deputy City Atty. Andre Quintero told the young woman about the crime she was charged with. “I’m not going to repeat it because it’s not you.”

The five defendants that day were graduates of the Rapid Diversion Program, an initiative in Los Angeles Criminal Court that is making a small dent in the disproportionate number of mentally ill offenders in the L.A. County Jail population.

Rapid diversion aims to identify candidates for mental health diversion as early as possible after they’ve been arrested so they can be shifted into community care without long stays in jail that would likely lead to further mental deterioration.

“Everybody understands that it’s better for the community and the person if we don’t just give them 10 days in jail and then put them right back out where they started,” said Nick Stewart-Oaten, appellate attorney with the L.A. County Public Defender’s office and the author of the state law that allows for the pretrial diversion. He started the diversion program in L.A. County.

Initially, only misdemeanor defendants were eligible for rapid diversion. Some felonies were later included. Most diversions are for low-level offenses often associated with mental illness: trespass, assault, vandalism and public intoxication.

In the county’s far-flung criminal justice system, the ideal place to catch people early is in court where inmates are funneled, ideally within 72 hours, for arraignment.

Among the thousands of defendants passing through daily, many stand out to public defenders as offenders whose crimes clearly arose from untreated mental illness.

In the past, their only option was to request a court-ordered psychiatric exam, a drawn-out process requiring a psychiatrist to be scheduled.

“That takes upwards of two months or more,” Stewart-Oaten said. “Someone sitting in custody might be decompensating that whole time.”

Rapid diversion places clinical staff inside the court to provide that evaluation on the spot.

In the Clara Shortridge Foltz Criminal Justice Center downtown, one of six courthouses that currently have rapid diversion programs, three teams of clinical social workers and case navigators are based in the public defender’s 19th floor office.

As the case files pile up in arraignment court — some days a handful, other days dozens —public defenders keep an eye out for cases that may qualify. If a follow-up interview confirms that a defendant is a candidate for diversion, the public defender calls for a clinical evaluation.

A social worker and case navigator come downstairs and speak with the defendant. With access to the county’s mental health records system, they can piece together a clinical history and make a recommendation: diversion with outpatient treatment, diversion with residential treatment or no diversion.

The public defender, city or county prosecutor and clinical team all have to sign off before diversion can be offered. Guidelines on what types of cases are eligible have been worked out in advance with the city attorney’s and district attorney’s offices. Line prosecutors generally agree with the assessment.

“There’s a lot of cases we agree on,” said Stewart-Oaten. “I thought the hardest part of my job would be convincing my colleagues. It turns out the hardest part is convincing the candidate.”

Many decline simply because they know they’ll be released in a few days.

Those who accept are enrolled in a treatment program usually lasting a year. It can last longer if they have setbacks, as many do. Participants meet weekly with their court case manager who reports to the judge on their progress. At any time the judge can revoke the diversion and restart the criminal case.

“We’re asking these folks to do a lot more than they’d be required to do if they just went forward with their criminal case,” Stewart-Oaten said.

The treatment program is prescribed by the clinical team.

“If our clinical team says you need a residential program, that’s the requirement,” Stewart-Oaten said. “What we try to do is get lawyers out of mental health decisions. Our lawyers have no input into the correct treatment program.”

Some candidates balk at a residential program. For those who accept, release may be delayed.

“Ideally, we’d like to assess and get into treatment the same day,” Stewart-Oaten said. “It won’t happen in every case until we have a bed available.”

In particular, acute care beds in locked facilities are scarce. To keep its emphasis on rapid, the program focuses on defendants with mid-level mental illness.

Often candidates have previously been in treatment, sometimes receiving care at home, when some setback or gap in service touched off an episode.

“A lot of time it’s a matter of reconnecting them and tweaking the gap,” Stewart-Oaten said.

In its nearly four years, Rapid Diversion has released more than 1,500 people out of detention. So far, 350 have graduated.

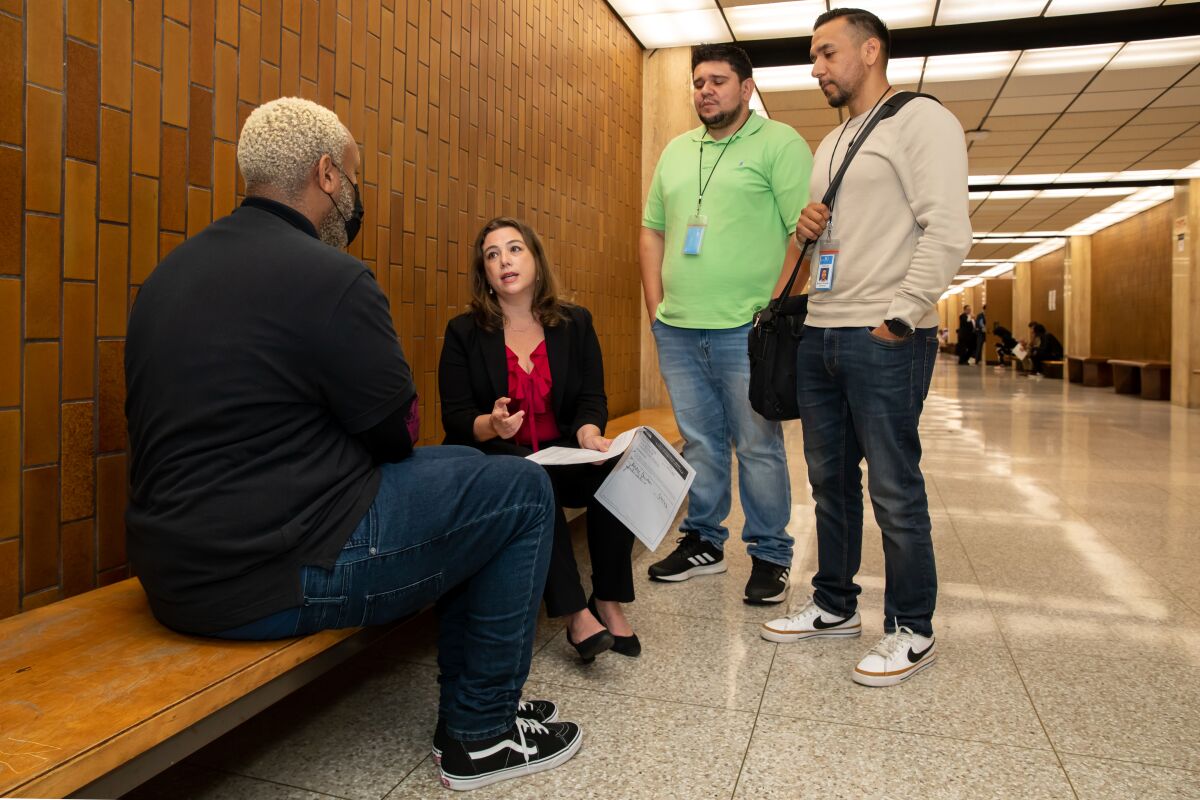

Coordinator for the Rapid Diversion Program and Public defender Caroline Goodson, left in red, flanked by resource navigator Brian Pineda-Recinos and case manager Raymond Gonzales, consults with a client who has been identified as a candidate for diversion from criminal proceedings. After spending about 40 days in residential treatment, the client was returning to court for a formal ruling diverting him from prosecution in Dept. 48, Clara Shortridge Foltz Criminal Justice Center, Los Angeles, CA.

(Irfan Khan/Los Angeles Times)

The graduation ceremony has become a valued element of the treatment, said Public Defender Caroline Goodson, countywide coordinator for the program who attends most graduations. The impersonal machinery of the court is suspended and the defendant’s narrative becomes the center of attention. Goodson starts each one with a tribute.

“I would love to tell you what Mr. V. has gone through,” she told the court as the defendant stood beside her with his case manager at his other side. (The Times is withholding the defendant’s full name at the court’s request because his criminal record has been expunged.)

“This is a real story of trauma and treatment,” she said. “Mr. V. has gone through so much. He experienced trauma as a youth when he was shot. He was then again shot in 2019 in his jaw. From that he suffered mental health issues. He was living on the streets homeless. He was estranged from his family.”

She then detailed his court-supervised treatment: Salvation Army shelter, job training, a sober living home with substance use services and in the near future, his own housing.

Then Quintero spoke for the city attorney’s office.

“I often say you had two paths to choose, an easier path and a hard path,” he said. “When you consider the charges, they’re serious charges. They involved a knife and they involved your family, right?

“So the fact that you’re reconnecting with them and going to church with them, that’s what we want for you. Ultimately that’s what we want for you, to have a better life and situation with your family.

“On behalf of the People of the State of California, we congratulate you and we’re proud of your work and we’re happy to not object to a dismissal.”

Judge Natalie Stone then added a slightly edgier last word.

“It wasn’t obvious that you were going to succeed, and it often isn’t,” she said. “So your example is really nice for me. I know it was really hard for you and tons of work went into this. You didn’t choose the easy road. You chose hard work, and I congratulate you.”

Then she stepped off the bench to pose with the defendant and his team for a group photo.

Goodson said she was stunned the first time she saw a judge step off the bench to connect personally with a client.

Now it happens almost every time and is part of a ceremony that has become a huge boost for clients.

“To hear them praising our clients like that and to hear the prosecution doing it, and doing it in a way that’s healthy and acknowledges that the client has accomplished so much is really powerful,” she said.

It’s too early to determine what the success rate for rapid diversion will be, but initial signs are encouraging, Stewart-Oaten said. So far, only 5% of graduates have returned with a new charge. About 70% who remain in the program are on track to graduate. And among those who dropped out without graduating and went back to court to complete their criminal cases, the recidivism rate only increased to 10%.

The Rapid Diversion Program began in 2019 with a $1.1 million MacArthur Foundation grant obtained by the public defender’s office and alternate public defender’s office with the assistance of a nonprofit called the Center for Court Innovation. The center, which since changed its name to Center for Justice Innovation, still consults with the county.

Funding has largely shifted to the county, though the MacArthur grant still pays some of the costs.

The program was absorbed into the L.A. County’s new Justice, Care and Opportunities Department established last year to depopulate, and eventually close, Men’s Central Jail by expanding community care for people being diverted or released from the justice system.

After starting downtown, it has expanded to a staff of 60 deployed in five more courthouses: the Airport, Van Nuys, Long Beach, Lancaster and Compton. A sixth program is scheduled to start in Pasadena by fall.

Stewart-Oaten said he fields calls from public defenders and prosecutors in other courts asking when they can get access to diversion.

The limiting factor, he said, is hiring the clinical staff.

“As soon as we can,” he tells them. “We have to find clinical staff, attorneys and navigator staff to expand.”

“This is not the conversation about how we solved everything,” Stewart-Oaten said. “This is the conversation about how we started to solve things. We started at zero diversions. We just hit 1,500. There is a ton more work to do here. We are aware of that.”