Terra Nil is a city-builder that’s not really a city-builder. It plays like one, so it’s easy to use that label as shorthand (developers Free Lives call it a “reverse city-builder”), but Terra Nil doesn’t ask you to lay any roads or worry about residential taxes. It’s more of a “resource management puzzle game” (publisher Devolve’s words) that borrows many of city-building’s systems and ideas.

Instead of being tasked with growing a huge metropolis on a big chunk of empty green grass, here you’re in charge of terraforming a desert over a series of maps with specific challenges. Confronted with a seemingly dead world, you need to take a succession of steps—most of them involving building something in the right spot—in order to breathe life into the environment, turning dusty plains into vibrant forests.

The first of those steps is normally to drop a few machines that draw out water from deep underground. Then build a few more little buildings that clean the soil. Overlap their areas of effect to grow some grass, then maybe see if you can plant some trees. Once those balls are rolling you might want to start fucking with the humidity levels to make everything wetter, and before you know it you’ll be growing your own coral and starting wildfires to encourage new growth.

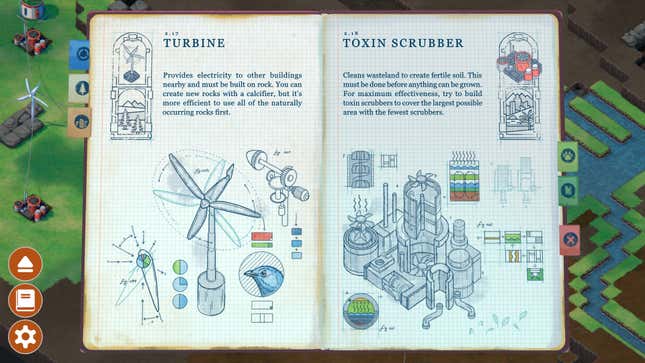

This is where Terra Nil is at its most city-buildery, because pretty much everything you place on the map is some kind of structure with some kind of effect on the world around it. Each one does a certain thing within a certain range, with effects on certain types of climates. As you can probably guess, this means you need to think very carefully about where you put each building, and it’s easy to swap out your traditional genre worries about fire station coverage for irrigation range without much hassle.

Terra Nil’s centrepiece is a fairly limited campaign focused on restoring a certain amount of life to its desert world, across a number of different regions, each with their own climate. It’s not even really a campaign, more of an extended four-mission tutorial, and there’s only so much you can do before it wraps up in surprisingly short order. Each map has a fairly linear sequence of things you need to build, so it feels more like moving down a checklist than genuinely freestyling your way through environmental problems.

Within those confines though—which are hallmarks of the city-building genre itself more than genuince criticism of this game in particular—I really liked it! The abstract setting means you can’t rely on assumptions of existing knowledge of what everthing does and how it works, and once you’re done with the campaign, later missions are where the game’s puzzle design can really kick in.

These maps are far more elastic. Where the first four missions move you in a straight line introducing you to all of Terra Nil’s terraforming toys, later objectives will ask you to drop some buildings down, change a little of the surrounding area but then dismantle them and do something completely different, in a totally different order than you were expecting, making their completion far more challenging (and interesting).

The best part of the Terra Nil experience, though, is that it’s not just a city-builder, it’s a city-dismantler. Maps don’t end once you’ve met their objectives; instead, they’ll only finish once you’ve packed up after yourself, because there’s no point in returning nature to its original state if you’re going to leave a bunch of deactivated pumps and scrubbers lying around. This involves powering down and recycling every single thing you built on the map, an immensely soothing and satisfying way to complete each mission.

This isn’t just any barren planet, it’s [Homer voice] our planet. Terra Nil might have fictional landmass shapes on its map screen, but the premise here is that, centuries into the future, we have so utterly destroyed the Earth that the whole thing is just one huge uninhabitable wasteland.

It is, spelled out like that, incredibly grim! To be presented with a world where we have failed our environment so utterly that we can’t live here, at all, not even in bunkers or bubbles, is confronting. Even Fallout, for all its ecological destruction, still has people walking around scratching out a living.

But then Fallout is just like every other post-apocalyptic (or at least post-climate change) story, from Cyberpunk to Mad Max. People might be clinging to life, but that life sucks. Everything around them is worse, and everyone is resigned to living in their dystopia. That bleakness defines those stories.

Terra Nil doesn’t dwell in misery, it’s about hope. Rather than showing us a good world then destroying it, it decides to start with the destruction and work backwards. Yes, things are bad—later levels reveal maps that aren’t just dead but poisoned—but the entire game is designed to let you do something about it. Saving the world not through a story, but by literally putting in the work.

This isn’t a simulation. Much of the tech you’re using here is fanciful at best, and on a less generous day utterly fictional. Terra Nil isn’t a blueprint for climate salvation, and it’s not pretending to be. This is just a puzzle video game.

But as someone prone to bouts of climate doom every time I read anything about carbon levels and ice sheets, Terra Nil was the ultimate form of video game escapism. A little diversion, no matter how unrealistic it is, that rather than asking us to live through the planet’s destruction let us try and recover from one instead.