Getty Images

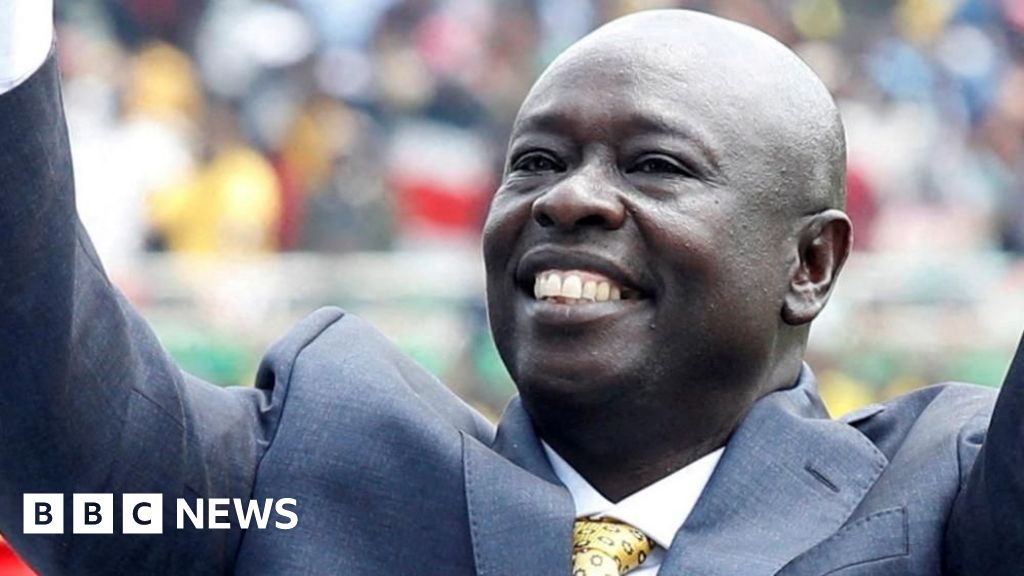

Getty ImagesMembers of parliament in Kenya have started the process of removing the country’s deputy president from office.

Those who back the effort accuse Rigathi Gachagua of having a role in June’s violent anti-government demonstrations, as well as involvement in corruption, undermining government and promoting ethnically divisive politics.

The deputy president has dismissed the allegations.

This is the culmination of a major fallout between Gachagua and President William Ruto.

On Tuesday, the speaker of the National Assembly allowed the impeachment proceedings to begin after a motion to start things off was backed by 291 MPs, way over the threshold of 117 MPs required.

The impeachment itself is expected to sail through both houses of parliament easily, after the main opposition joined forces with the president’s party following the recent protests. But there is no date yet for when that will actually take place.

Multiple efforts to stop the impeachment attempt through the courts failed.

The power struggle between the president and his deputy has led to concerns of instability at the heart of government, at a time when Kenya is in the throes of a deep economic and financial crisis.

Ruto chose Gachagua as his running-mate in the 2022 election, when he defeated former Prime Minister Raila Odinga in a bitterly contested election.

Gachagua comes from the vote-rich Mount Kenya region, and helped marshal support for Ruto.

But with members of Odinga’s party joining the government after the youth-led protests that forced Ruto to backdown from increasing taxes, the political dynamics have changed – and the deputy president looks increasingly isolated.

Gachagua has, however, struck a defiant tone, saying he has the backing of voters in his native central Kenya region.

“Two-hundred [legislators] cannot overturn the will of the people,” he said.

For the motion to pass, it would require the support at least two-thirds of members of the National Assembly and Senate, excluding its nominated members.

Backers of the motion are confident that it will be approved.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut Gachagua has made it clear that he will not go down without a fight.

“The president can ask MPs to stop. So, if it continues, he’s in it,” he told media outlets before Tuesday’s parliamentary session.

Ruto has in the past vowed not to subject Gachagua to “political persecution”, similar to what he says he experienced when he was deputy to his predecessor, Uhuru Kenyatta.

But the rift between Ruto and Gachagua has been apparent in recent months.

The deputy president has been conspicuously absent from seeing off his boss at the airport when he travels abroad, and receiving him when he returns.

Interior Secretary Kithure Kindiki, a law professor who is trusted by the president, appears to be taking on some of the deputy president’s responsibilities – something that also happened when Ruto and Kenyatta fell out.

Like Gachagua, Kindiki comes from Mount Kenya – the region which forms the largest voting block in Kenya.

Dozens of legislators have rallied behind Kindiki as the region’s preferred “mouthpiece”, intensifying speculation that they are pushing for him to succeed Gachagua.

That has left the deputy president largely isolated with only a handful of elected politicians backing him.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn a further sign that he is in political trouble, the police’s Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI) recently recommended charges against two MPs, a staff member and other close allies of the deputy president, after accusing them of “planning, mobilising and financing violent protests” that occurred in June.

Gachagua defended the accused, denouncing the charges as an “act of aggression” and an “evil scheme” to “soil” his name and lay the groundwork for his impeachment.

In parliament last week, Kindiki – under whose ministry the DCI falls – pledged to remain neutral, but made it clear that “high-level individuals” will be prosecuted.

“We are dealing with the aftermath of the attempted overthrow of the constitution of Kenya by criminal and dangerous people who almost burnt the parliament of Kenya. We have a job to do,” he said.

But many of the young people who were at the forefront of the protests dismiss suggestions that Gachagua’s allies were behind it, and see the bid by lawmakers to oust him as an attempt to deflect attention from bad governance.

They say that if the deputy goes, the president must go too.

In the Senate, an opposition legislator has filed a censure motion against the president. It does not bear the same weight as impeachment and has no legal consequence.

Ruto, who is expected to host legislators from his party later this week, will be weighing the political risks of moving against Gachagua, but some lawmakers say they do not want him to wade into the debate – a tough ask.

For now, Gachagua’s fate rests with legislators, but one man might still extend him a renewed lease of political life – the president.

More Kenya stories from the BBC:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC