This article is an onsite version of our Europe Express newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday and Saturday morning

Good morning and welcome to the Europe Express Weekend newsletter. I’m back to discuss one of the most interesting questions from the past seven days: the role of religion in Europe’s sharpest political controversies. Thanks for voting in last week’s poll: more than 80 per cent of you feel Germany is not doing enough in response to the war in Ukraine.

I trust it didn’t escape your attention that Pope Francis published a message this week to mark the forthcoming Second World Day for Grandparents and the Elderly.

Francis didn’t blame Vladimir Putin for unleashing the violence in Ukraine (“a pope never names a head of state,” he said last month). Nor on this occasion did he criticise Patriarch Kirill, the head of the Russian Orthodox Church, for supporting Putin’s invasion.

Two weeks ago, however, the Argentine-born pope spoke out in uncompromising language against the war. Francis said the atrocities in Ukraine, attributed to Russian forces, recalled the Rwandan genocide of the 1990s. He also warned Kirill not to turn into “Putin’s altar boy”.

These remarks drew a scolding rebuke from the Moscow patriarchy, underlining that Putin’s war has exposed sharp differences between the Roman Catholic Church and the official Russian branch of Orthodox Christianity.

How much brighter things looked in 2016, when the pope and Kirill held talks and embraced each other in the Cuban capital of Havana. This was a truly historic meeting — the first between the leaders of the Catholic and Russian Orthodox establishments since the creation of the Moscow patriarchate in 1589.

But now Francis has called off a second meeting with Kirill that had been pencilled in for next month in Jerusalem. The estrangement between the two leaders could hardly be more acute. What does this tell us about the way that the war is entangling religion with Russian-western geopolitical rivalry?

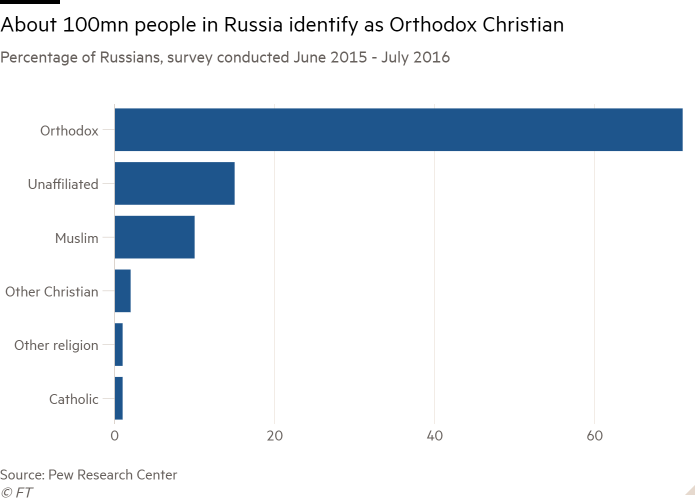

In the first place, it shouldn’t surprise us that the Russian Orthodox Church — with the exception of some very brave low-ranking priests — is firmly at Putin’s side. As in other Orthodox countries, religious faith in Russia has deep historical ties with national identity and state authority.

But the second, more important, point is that, under Kirill, the church hierarchy is taking up cudgels on Putin’s behalf and arguing that Russia is defending Orthodox Christianity against a godless, degenerate west.

This is more than mere propaganda. For Kirill, it is a sacred cause. For Putin, it is a political project that, he calculates, will gain strength from the long Orthodox tradition of nurturing an obedient patriotic citizenry.

In a perceptive article for the New Statesman, Rowan Williams, who served as Archbishop of Canterbury from 2002 to 2012, wrote:

Vladimir Putin sees himself as the protagonist in a battle for the survival of an integral Christian culture as surely as Islamic State casts itself as the defender of Islamic cultural purity . . .

Patriarch Kirill of Moscow made it clear in an extraordinary sermon delivered on March 6, the day before Orthodox Lent began, that he regarded the Russian campaign as a war to defend Orthodox civilisation against western corruption, of which gay pride marches were singled out as the leading symptom.

In taking his stance, Kirill sees eye to eye with several descendants of famous Russians from the whole spectrum of tsarist and Soviet history.

Pyotr Tolstoy, the great-great-grandson of Leo Tolstoy, author of War and Peace (and a strict pacifist in his later life), growled in an Italian newspaper interview that Russia must “totally de-Nazify” Ukraine and not stop the war until its armed forces have reached the Polish border.

Then there is Vyacheslav Nikonov, grandson of Vyacheslav Molotov, Joseph Stalin’s foreign minister and a man with much blood on his hands during the mass Soviet repressions of the 1930s. “This is truly a holy war we’re waging and we must win,” Nikonov says.

This is the sort of hyperbole to which we have become accustomed in the Putin era. Yet the religion-inflected tensions between Russia and the west are real. On Friday, Cardinal Pietro Parolin, the Vatican’s secretary of state, suggested that western supplies of weapons for Ukraine’s self-defence were justifiable under the Church’s doctrine of a “just war” — an argument certain to go down badly in the Kremlin.

Notable, Quotable

Those with coasts and seaports can import oil by ship from anywhere in the world, but there are countries that don’t have sea coasts. We’d have one if it hadn’t been taken from us — Viktor Orbán, prime minister of Hungary

Today I’ve chosen this eye-catching statement which my colleague Val also flagged in Thursday’s edition of Europe Express. Here Orbán infuriates Croatia by lamenting the “loss” of Rijeka, once part of the Habsburg empire and now in Croatia. It’s a rare example of two countries in the EU squaring up in a historical dispute over territory.

Tony’s picks of the week

-

Don’t miss this gripping account by Clive Cookson, the FT’s science editor, of Nasa scientists who are testing new spacecraft to prevent asteroids from striking Earth

-

Securing access to vital minerals and metals is a strategic imperative for the EU, write Tobias Gehrke and Mart Smekens in a policy brief for the Egmont Institute, a Brussels-based think-tank

Are you enjoying Europe Express? Sign up here to have it delivered straight to your inbox every workday at 7am CET and on Saturdays at noon CET. Do tell us what you think, we love to hear from you: [email protected]. Keep up with the latest European stories @FT Europe