Starting next year, the number of high school graduates will start to fall in Mississippi. That’s the looming reality a joint hearing of the House and Senate Colleges and Universities committees zeroed in on Wednesday.

In Mississippi, this trend, called the “enrollment cliff,” will force the largely tuition-dependent colleges and universities to compete for a shrinking pool of students. Regional institutions like Delta State University, Mississippi University for Women and Mississippi Valley State University, all of which are already struggling with enrollment, will be especially hurt.

The state is poised to see the second-worst decline of high school graduation rates in the Southern U.S. by 2027 after Virginia, according to data presented by Noel Wilkin, the University of Mississippi’s provost and executive vice chancellor for academic affairs.

The committee wanted to know: What is the Institutions of Higher Learning Board of Trustees, the governing body for Mississippi’s eight public universities, doing about this?

“When can we expect a report to detail those recommendations and strategies for the future,” Sen. Scott DeLano, R-Biloxi vice chair of the Senate committee, asked Al Rankins, the IHL commissioner.

“Whenever you’d like to see a report,” Rankins responded. IHL has been talking about the enrollment cliff for years, he added, and has a working group focused on the regional college’s unique needs.

Kell Smith, the director of the Mississippi Community College Board, which operates differently from IHL, attended the hearing but did not present. He said MCCB doesn’t have a strategic plan for the enrollment cliff but some of the individual community colleges might.

“Very simply — how can we fix the problem to prepare for 15 years from now?” Rep. Donnie Scoggin, R-Ellisville the House chair, asked Wilkin.

There are few simple answers. The enrollment cliff is unavoidable, the product of declining birth rates that will be exacerbated by out-migration from Mississippi and deaths due to the COVID-19 pandemic, John Green, a Mississippi State University professor, told the committee.

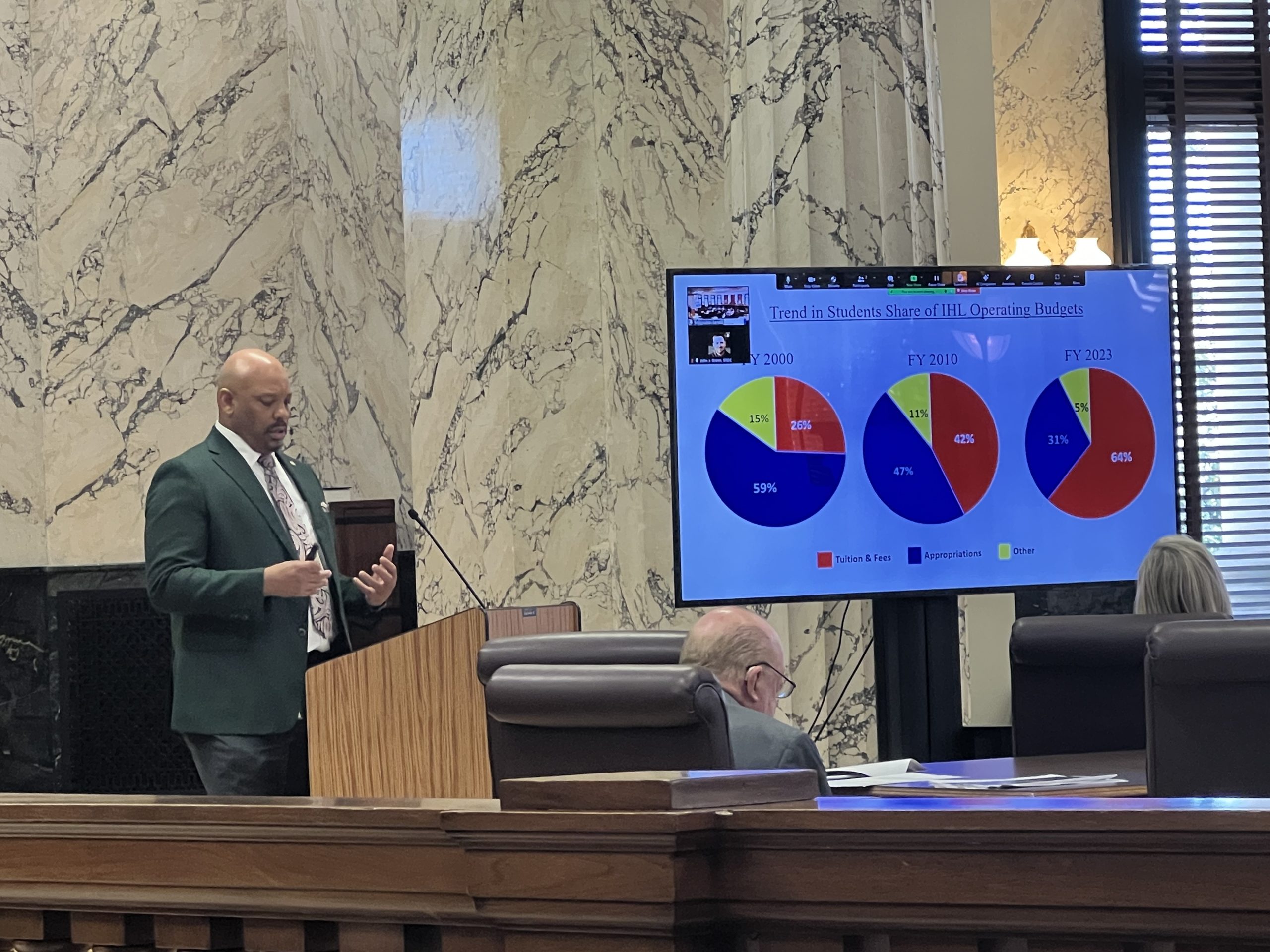

But the changing economics of higher education is largely the result of funding choices by the Legislature years ago. In Mississippi, the four-year public universities are all more dependent on tuition than they are state appropriations.

Rankins presented a chart showing that in 2000, state appropriations supported nearly 60% of the universities operating budgets, while tuition was 26%. In fiscal year 2023, that ratio had basically flipped, with tuition supporting 64% of operating budgets.

This raises the question: If Mississippi’s colleges and universities are increasingly reliant on student tuition, not taxpayer dollars, are they still a public service?

It’s complicated, said Rep. Lance Varner, a member of the House committee, whose 16-year-old daughter has started getting recruitment letters from out-of-state colleges hoping to attract her away from Mississippi.

“If you own a business, your goal is to try to get people to come to your business,” he said.

At the same time that he thinks higher education is a public good, Varner, R-Florence, said he bets the universities wish they could be even less dependent on state appropriations.

“Every one of those colleges is working hard to make sure they’re self-sufficient,” he said. “They don’t want to depend on the Legislature.”

At the University of Mississippi, tuition and fees now represent 78% of its total operating budget, according to IHL’s presentation, the highest of any public university.

A huge driver of that is the number of out-of-state students, who pay nearly three times more for tuition than Mississippi residents, now make up half the university’s total population of more than $21,000, Wilkin told the committee. This is one way Ole Miss is responding to the enrollment cliff, which it started preparing for in 2017.

“We have become a destination state for higher education,” Wilkin said.

University of Mississippi netted $62 million in tuition from in-state students in fiscal year 2023 — but brought in $188 million from non-resident students. It’s a crucial revenue source that, Wilkin said, allows Ole Miss to keep its costs down for in-state students.

“If I were to take all the revenue that comes from in-state students and all the state appropriations we get and compare that to what it costs us to educate those students, we’re still left with a multimillion-dollar hole,” Wilkin said.

Wilkin also discussed the “intangible” aspect of higher education that shapes if, why and where students attend college, especially in light of the fact high school graduates are becoming more diverse.

“All of us see there have been questions raised about the value of a higher education degree today,” he said.

By 2036, white students are projected to comprise 43% of high school graduates compared to 51% today. Black students will increase from 25% to 28%.

Smith, the MCCB director, said after the meeting that community colleges need to be focusing more on students who don’t have a high school diploma.

“We need to go after those students irregardless of what the enrollment cliff looks like,” he said.