Long before he became one of the most powerful judges in the country, James Ho sat down with one of his heroes, Edwin Meese III, in Washington, D.C. Ho was 26, fresh out of the University of Chicago Law School, and had come to interview Meese for a law journal article. Sixty-seven-year-old Meese had been a conservative star since the eighties, when he ranked among President Ronald Reagan’s most trusted aides, serving as counselor and attorney general. He had endeared himself to Christian leaders by declaring in a speech that out of all the laws written by mankind, “we haven’t improved one iota on the Ten Commandments.” Meese had resigned in 1988, after an independent counsel investigated possible ethics violations, then drifted into Washington’s small pond of former big fish.

His meeting with Ho, in 1999, marked a symbolic passing of the torch, from an old-guard Republican to a young turk. They spent most of their time talking about a rising conservative legal theory known as originalism. Meese had been evangelizing for the doctrine since 1985, when he publicly lambasted what he saw as the overreach of the federal judiciary. In his view, judges had inferred the existence of rights that weren’t spelled out in the Constitution. He called instead for “a jurisprudence of original intention”—interpreting the Constitution by adhering as closely as possible to its eighteenth-century meaning.

Originalism wasn’t entirely new. The concept had been bandied about since 1971, when conservative legal scholar Robert Bork gave a lecture that helped lay its foundations. But Meese’s speech—and the outraged reaction to it—raised its profile. Critics of the doctrine said it was foolish to limit Americans’ rights to those enumerated in a document mostly written in the eighteenth century. But by 1999, originalism had attracted numerous adherents—and a particularly energetic one in young Jim Ho.

His meeting that year with Meese wasn’t the first encounter between master and student. A year earlier, the older man had invited Ho to attend a Heritage Foundation forum and present his law-review article arguing that President Clinton had bypassed the Senate and made an unconstitutional appointment of a controversial assistant attorney general—an article that conservative columnist George Will had lauded.

During the interview with Ho, Meese praised originalism’s chief proponents on the Supreme Court, Justices Clarence Thomas—whom Ho would go on to clerk for—and Antonin Scalia. They shouted out the Federalist Society for revitalizing originalism, particularly through its presence at law schools. (Ho had joined a chapter during his first year at the University of Chicago.) Ho noted originalists’ objection to the “administrative state,” referring to the federal agencies created in the modern era to protect the environment and public health and otherwise regulate businesses. “Many originalists consider large portions of the administrative state to be unconstitutional,” said Ho. Meese said, “I’m very much in favor of having Congress carve back the administrative state.”

For a young person to seek out an old power broker, notebook in hand, is a classic sign of ambition, telegraphing that Ho was unlikely to fade away into an anonymous career as a corporate litigator. Toward the end of his interview with Meese, there was perhaps another sign when Ho asked, referring to the Supreme Court, “Do you have any predictions or suggestions with respect to who might be the next great originalist nominee?”

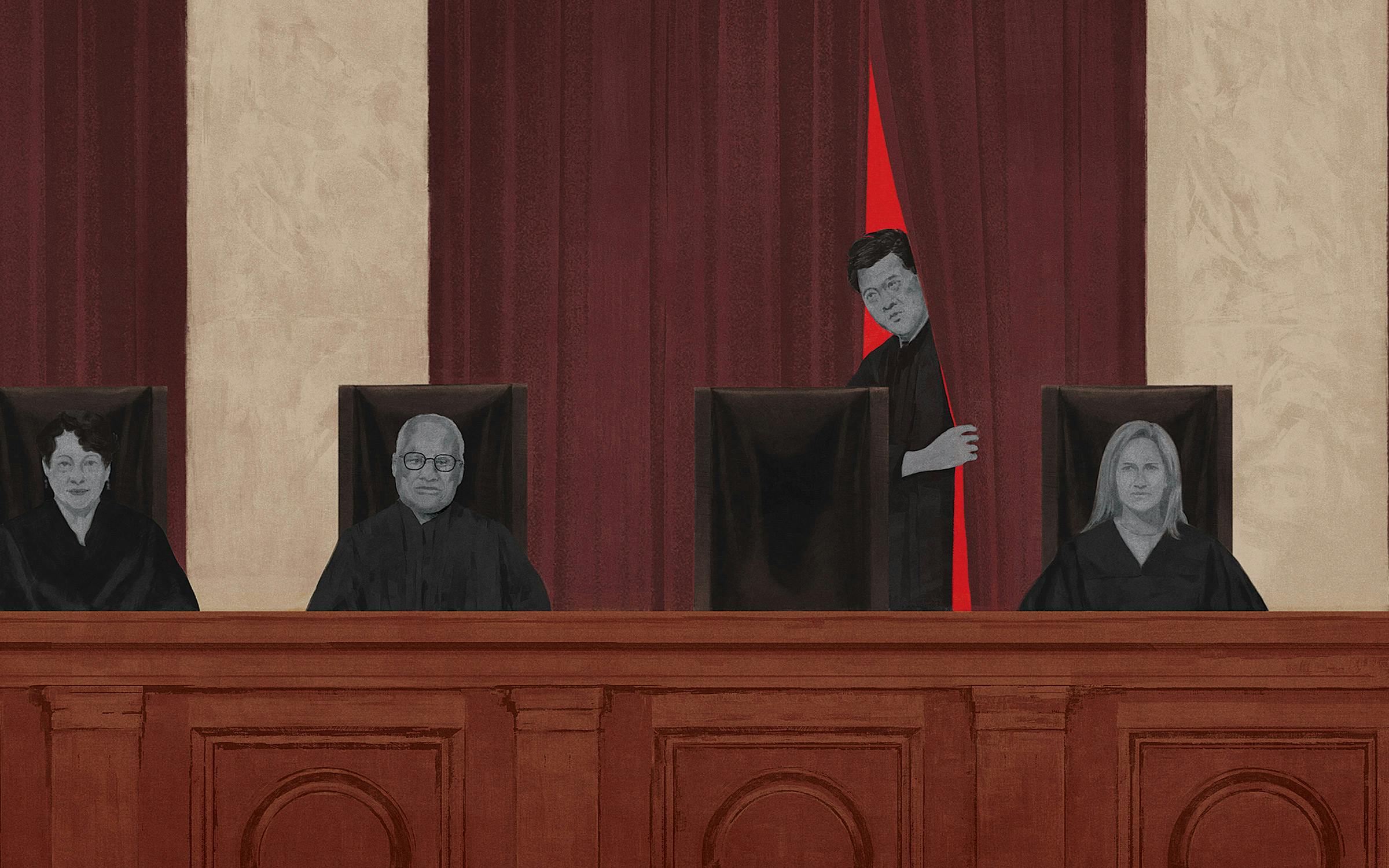

“I really don’t,” Meese answered. A quarter century later, Ho, the first Asian American judge on the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, just might become such a nominee, if Donald Trump wins the presidency in November. It is the hope of many of the faithful, as Ho has become a forceful and unusually public advocate for right-wing legal and political issues, especially when it comes to restricting access to abortion. In one of his early opinions as a Fifth Circuit judge, from 2018, he called the procedure “a moral tragedy”—words that, along with another ruling of his the following year, helped lay the groundwork for Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the 2022 Supreme Court decision eliminating a constitutional right to abortion. His name has appeared on judicial-nominee short lists from conservative groups and is expected to appear on Trump’s list. (Ho did not respond to interview requests, and some who know him would only speak if granted anonymity.)

Last year Ho made another visit to D.C. and the Heritage Foundation to speak at its Edwin Meese III Center for Legal and Judicial Studies. In the course of the introductions, a speaker noted that Ho had clerked for Thomas, then added, “Many of us, of course, would be happy to see Judge Ho serve as Justice Thomas’s colleague on that court.”

The crowd applauded enthusiastically, and Ho walked to the dais. A short man with a large head, he was supremely at ease—funny and self-deprecating but with an undercurrent of seriousness. “I didn’t enter this world as an American,” said Ho, who was born in Taiwan. “But I wake up every morning thanking God that I will leave this world as an American.”

Ho pivoted nimbly from one idea to the next in his characteristically assertive fashion. (As he articulates one thought, you can picture the next gathering in his head.) Arguing in favor of originalism, he complained that proponents of that approach have been maligned by woke cultural elites as “fundamentally bad people who are just too extreme for polite society. We’re mean-spirited, racist, sexist, homophobic. We’re just trolling or auditioning. We’re unethical if not corrupt.”

Most federal judges will concede, at least to friends, that their political philosophy—their sense of what constitutes a just society—influences their jurisprudence. But most take care not to cross the line into combative public partisanship. Ho is a different kind of federal judge. He is a brash right-wing Republican, groomed in Texas politics, appointed by Trump, and openly pushing a conservative agenda. He’s devoted to the cause of recovering what he describes as the original meaning of the Constitution, which was written when slavery was legal, flogging was widespread, women couldn’t vote, homosexuality was punishable by death, and businesses could generally treat their employees in whatever way they pleased. Ho has fought, and spoken out against, affirmative action, gun control, and vaccine mandates. He’s sought to dismantle long-accepted federal regulations. And he’s sided with those who say their religious beliefs should exempt them from laws that forbid discrimination against LGBTQ Americans. While much of his ideological tilt seems derived from his upbringing in a wealthy Republican suburb—along with his education among the conservative legal minds at the University of Chicago’s law school—some of it may also reflect a troubling part of his family history: his father, Steve Song-Shan Ho, was an ob-gyn who, according to California and New York state records, appears to have had a checkered career that ultimately resulted in the revocation of his medical license after he’d botched numerous abortions. (Steve Ho did not respond to interview requests.)

In many ways, Ho reflects the man who appointed him to the Fifth Circuit. But while Trump often behaves in an oafish and arrogant manner, Ho is typically polite and decent. A wealthy devout Christian, Ho has also become an expert at channeling conservative anger. For critics on the left such as Joe Patrice, who writes for the legal website Above the Law, Ho’s partisan rhetoric is a means to an end, “one of the thirstiest and most shameless campaigns for high federal judicial office in history.” Josh Blackman, a conservative professor at South Texas College of Law Houston and a friend of Ho’s, counters that there’s no such calculation behind Ho’s jurisprudence or public statements. “People don’t want to believe this is actually what Ho is like,” said Blackman, “so they make up these stories: ‘Oh, he’s auditioning. That’s the only reason he would ever do this.’ Well, the reality is: this is who he is.”

James Chiun-Yue Ho was born in Taipei in 1973, and the family immigrated to the U.S. soon after, settling first on Long Island and then in the late seventies moving to San Marino, an affluent town northeast of Los Angeles. With its wide, safe streets and its excellent library, botanical garden, and art museum, San Marino was a magnet for upper-income immigrants from China and Taiwan. During the eighties, the town’s Asian population quadrupled, and San Marino became known as “Beverly Hills for Asians.” Ho’s family fit right in.

San Marino was conservative—the John Birch Society had installed its West Coast office there by the early sixties—and anti-communist. In that way, too, the Ho household was well suited to the community. “Jim hates communist China, as most Taiwanese understandably do,” said a friend of his. He became a naturalized citizen and attended Polytechnic School, a small private institution in Pasadena. In 1991 the Ho family was featured in a Los Angeles Times article about San Marino, which described them as living in a six-bedroom, seven-thousand-square-foot colonial-style house worth $2 million (around $4.5 million today). Jim helped start a school newspaper. His coeditor, Joe Mathews, would later write that “Jim was super-intense; he walked fast, laid out pages fast, and drove too fast, in a Ford Probe.” Mathews also wrote that “Jim loved arguing with our classmates and wrote with a passionate, sometimes over-the-top style.” The child was clearly going to be father to the man.

Ho did a little of everything: he acted and danced in a musical and played as a lineman on the football team, though, as he later joked, “I had no athletic ability.” In his senior yearbook photo, Ho wears a big smile, next to a page of pop lyrics by Billy Joel and the Eagles and a quote from George H. W. Bush promising success in the Gulf War: “We will not fail.”

As an undergraduate at Stanford, Ho engaged with politics and wrote for the school paper. He didn’t always agree with his peers, but, he later said, “We’d duke it out in the student lounge, and then we’d have fun together. And that’s, to me, what this country is all about.”

After earning a bachelor’s degree in public policy with honors in 1995, he spent a year working as an aide to a state senator and was accepted by the University of Chicago’s law school. It was there, back in 1982, that Professor Antonin Scalia had helped found the Federalist Society, whose members were united by their loathing of expansive interpretations of the Constitution, and it was there that Ho’s conservatism burst into full bloom. He joined the Federalist Society, served on the law review and as an editor for a new law journal, the Green Bag, founded with the intention of making legal writing more entertaining. Ho did his part, later writing in one case summary, “Obedience to the Church of Marijuana is not enough to trigger the protection of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. Such protection might have been available had defendant smoked dope for God, however.”

Ho was already making a national name for himself. He wrote a piece for the Federalist Forum, calling for an end to all restrictions on campaign contributions by wealthy individuals and companies, as well as the law-review article that earned him the attention of Ed Meese and George Will. He graduated from law school with high honors, then clerked for Judge Jerry E. Smith, a Texan on the Fifth Circuit who just a few years before had written the majority opinion in the landmark anti–affirmative action case Hopwood v. Texas, which forbade the University of Texas’s law school from considering race in its admissions process. The job was in Houston, where Ho started dating Allyson Newton, a law student working at a Houston firm for the summer. She was seven years older and had earned a doctorate in English at Rice University.

He then took a job with the establishment firm Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher in Washington, D.C., where he helped one of its partners, Ted Olson, represent George W. Bush in the case Bush v. Gore, which determined the winner of the 2000 presidential election. Ho had begun his journey into politics, and after a stint in the Justice Department, in 2003 he became a top legal adviser to Texas senator John Cornyn, serving on the Senate Judiciary Committee staff. Two years later he clerked for Clarence Thomas, one of his heroes.

Allyson was a top lawyer too, having worked for President Bush and U.S. attorney general John Ashcroft and clerked for U.S. Supreme Court justice Sandra Day O’Connor. The couple married in 2004, and because Allyson wanted to go back to Texas, in 2006 they moved to Dallas, where Ho returned to Gibson Dunn, but not for long. He had also befriended Ted Cruz, who recruited Ho to replace him as the state solicitor general, a key role in the state attorney general’s office. Under Cruz, the office had often waged ideological war against the federal government, opposing abortion rights and gun control. The office didn’t always win, but it made a lot of noise and attracted attention from conservatives nationwide.

Greg Abbott, then the attorney general of Texas, hired Ho, who continued the fight, leading a team of twenty assertive lawyers who were often at odds with the Obama administration. In his nearly three years as solicitor general, Ho convinced the Fifth Circuit that adding the words “under God” to the Texas Pledge of Allegiance (as the Legislature recently had done) was constitutional. After the Fifth Circuit set aside a death sentence, he persuaded the U.S. Supreme Court to reinstate it—which the court rarely does. “It’s frankly a little embarrassing to describe how much fun this job is,” he said in 2009. His charges loved him. “Jim Ho is one of the hardest-working people I’ve ever met,” said one of them. “Just works like a crazy man. And he’s just a nice person. I mean, with a capital N.”

As Jim Ho’s career took wing, though, Steve Song-Shan Ho’s sank into disgrace. During the nineties, the physician was sued multiple times for medical malpractice; at least two cases led to monetary judgments against him. He separated from his wife and by 2000 had moved back to New York. Over the next decade, serious complaints were filed against Steve Ho, and in early 2010 the New York State Board for Professional Medical Conduct revoked his license, based on a review of seven different cases in which patients had sought abortions. The review was stunning, a litany of nightmares: perforated uteruses, extensive corrective surgeries, a hysterectomy. In several instances he left fetal body parts inside his patients, and in one woman, “a free floating, intact fetus.” In a 2004 abortion, after Ho had performed the procedure at a Brooklyn surgery center, his patient was in so much pain that she begged to be taken to a full hospital; he tried to give her a $20 bill to take a taxi home instead. The report noted that the doctor “has apparently left the country and moved to Taiwan without leaving a forwarding address.”

Meanwhile, in Texas, James Ho (who appears not to have publicly commented on his father’s medical career) continued to thrive. From the AG’s office, Ho went back to Gibson Dunn, where he made partner, and also worked without pay for the First Liberty Institute, a conservative religious legal organization. Arguing that discrimination against gay Americans should be legal when motivated by religious convictions, the group had famously defended a family-run Oregon bakery after it declined to make a cake for a same-sex wedding. One of Ho’s big wins was advocating successfully for the right of cheerleaders in the southeast Texas town of Kountze to paint Bible verses on their football-game banners.

By this point, Allyson and Jim Ho had a twin son and daughter and were living in a 7,200-square-foot Tudor-style home in the tony North Dallas neighborhood of Preston Hollow. Allyson, working for another firm, was becoming as distinguished an appellate lawyer as her husband, arguing several times before the U.S. Supreme Court. Ho maintained his Federalist Society connections and rallied support for Cornyn’s and Cruz’s campaigns. In 2015, when Cruz was running for president, a fresh-faced and earnest Ho declared in a campaign video that “there is no one in my generation who has done more to champion constitutional conservative causes than Ted Cruz.” Ho had come a long way since moving to Texas, rising, along with Allyson, into the ranks of the Republican elite.

And then he rose even higher, when Trump nominated him to the Fifth Circuit. In January 2018 he was sworn into office in the massive Highland Park home of Harlan Crow, the Dallas billionaire and Republican benefactor whose previously undisclosed generosity to Justice Thomas was reported last year by ProPublica. Thomas performed the swearing-in, held in Crow’s private library, a sanctuary of dark wood, tall ceilings, and expensive art—not far from the estate’s noted “Garden of Evil,” which is studded with statues of dead Communist dictators, including Lenin and Stalin. Cruz attended, and on Twitter he posted a photo of the whole gang, dwarfed by a gigantic fireplace. Allyson, positioned just behind her husband, holds out a large antique Bible, and Ho, with his left hand planted on top of it, stares solemnly ahead. It almost looks as if he’s girding for a fight.

Traditionally, judges have striven to be, well, judicious. They’ve promised to prudently interpret the law rather than seek to remake it. As Chief Justice John Roberts said during his confirmation hearings: “I will remember that it’s my job to call balls and strikes and not to pitch or bat.” Off the field, they’ve stayed quiet. If they gave speeches, it was to Rotary Clubs or bar associations, and they generally stuck to banalities about the rule of law. They avoided politics because they didn’t want to appear partisan. They were boring—on purpose.

Jim Ho isn’t like that. “He’s a political animal,” said a friend. “He loves politics, he loves gossiping about, you know, who’s going to be the new judge on the border.” He also loves hanging out with other true believers at Federalist Society meetings. “I think Judge Ho’s view of his role as a judge is that it provides a platform,” said Blackman, the law professor.

In his first judicial opinion, three months after joining the Fifth Circuit, he railed against “big government” and proclaimed his originalist beliefs: “The unfortunate trend in modern constitutional law is not only to create rights that appear nowhere in the Constitution, but also to disfavor rights expressly enumerated by our Founders.”

In person he was less dogmatic. When lawyers argued before him, Ho would usually engage with them, while some of his fellow judges sat silently. He was sharp, well prepared, and genial, and for the most part he got along with colleagues. “I loved talking about cases with him more than just about anyone on the court,” said former Fifth Circuit judge Gregg Costa. “He wasn’t there just for the prestige of being a judge. He was there because he cared about the law and ideas.”

On paper, though, Ho’s confidence sometimes crossed the line into arrogance. In 2020, responding to a dissent written by Judge Jacques Wiener, who was then 86, Ho wrote, “The loudest voice in the room is usually the weakest.” Court watchers were shocked by the tone of Ho’s opinion, written, another federal judge said, “for the sole purpose of bench-slapping a well-liked and long-tenured colleague.”

Some of Ho’s originalist legal arguments were propelled more by oratorical force than by legal history or logic. Consider the horrible case of an unarmed Arlington man who, during a mental health crisis, drenched himself in gasoline and threatened to light himself on fire, only to be set ablaze instead

by police officers who used their Tasers on him. In 2021, Ho was part of a majority that denied a rehearing of the case, after a three-judge panel had said the officers had no apparent options to avoid disaster—and were protected from a lawsuit by the doctrine of qualified immunity.

Ho’s colleague Don Willett, a fellow Trump appointee and no bleeding-heart liberal, wrote in a dissent that the cops’ actions were excessive, an “obvious” violation of the Fourth Amendment. “How is it reasonable,” Willett wrote, “to set someone on fire to prevent him from setting himself on fire?” In a response to Willett’s dissent, Ho defended the police and thundered, “As judges, we apply our written Constitution, not a woke Constitution.” Of course, the written Constitution says nothing about qualified immunity for police officers, and jurisprudence dating back to the eighties has considered the use of excessive force by police to be an infringement of Fourth Amendment rights. But Ho had a partisan point to make.

Critics of originalism, including some conservative jurists, find it incoherent in practice—a rationale used by right-wing judges to cherry-pick an interpretation of the Constitution that suits their politics. “As a matter of course,” said former federal judge Royal Furgeson, “the originalists seem to be able to reach the result they want through originalism. How fortunate is that?” Indeed, Ho’s legal opinions can be hard to distinguish from the op-eds he’s written over the years. “Even if you agree with him,” said one appellate attorney, “that’s not a judicial opinion—that’s something else. He’s telling us what he thinks about some kind of political issue.”

Ho is a product of the polarized times, influenced by the president who appointed him and his peers at the Federalist Society, who believe that even long-standing precedents should be overturned if they are based on rights not explicitly enumerated in the Constitution. “And the more colorfully, persuasively, and firmly you do it,” said a former judge, “the more acclaim you get within this important circle of very brilliant people.” Ho belongs to a cadre of right-wing judges on the Fifth Circuit who seek to demolish much of the federal government. Last year, for example, he ruled that the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission didn’t have the authority to license a nuclear waste storage facility, even though courts have repeatedly maintained that Congress gave the NRC that power.

Ambitious judges sometimes advance arguments that they hope will draw attention from the U.S. Supreme Court justices, and Ho has done this effectively. “You can draw a straight line between Ho’s opinions about the unconstitutionality of abortion in 2018 and 2019 and the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs in 2022,” said Blackman.

Seeking to further restrict abortion rights, Ho has continued to put forth novel lines of reasoning. In 2022 a coalition of antiabortion doctors and other medical professionals incorporated in Amarillo, then sued in federal court to rescind the approval of mifepristone, a drug used to terminate early-stage pregnancies that the federal Food and Drug Administration had declared safe in 2000. Normally, before plaintiffs can sue, they must be able to show they have been injured by the defendant—that they have “standing” to bring a claim. In this case, the allegation by doctors—represented by the Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF), a conservative Christian legal group—was largely that they might someday have to treat women who had experienced negative reactions to the drug. Many judges would have denied standing, but conveniently enough the plaintiffs had filed their case in the Amarillo court of Matthew Kacsmaryk, a Trump appointee (and a friend of Ho’s). Kacsmaryk agreed that the doctors had standing and threw out the FDA’s approval.

When the Fifth Circuit issued its ruling in August 2023, the court upheld the plaintiffs’ standing but ruled that the drug was still legal, with some limitations. That’s when Ho stepped in, penning a thirty-page opinion in which he not only called for outlawing the drug outright but offered the doctors an entirely new basis for establishing their standing to sue. “Unborn babies are a source of profound joy for those who view them,” he wrote. “Doctors delight in working with their unborn patients—and experience an aesthetic injury when they are aborted.” The idea of “aesthetic injury” came from environmental law; Ho cited cases in which groups of nature lovers were granted standing to sue to protect threatened species and habitats. For Ho, doctors had as much a right to see the birth of a baby—and indeed to compel that birth—as wildlife enthusiasts had a right to see beetles and butterflies. To many lawyers, such as the Nation writer Elie Mystal, the opinion was “inane and insulting.” To others, it was Ho as usual. “He pontificates so aggressively,” said a former federal judge. “He is coming at everything from an advocacy point of view.” Then again, considered in light of Steve Ho’s medical misconduct, Judge Ho’s theory of aesthetic injury presents itself as a kind of compensatory vision, one in which right-thinking, fetus-cherishing doctors stand in opposition to the negligence and incompetence of abortion providers like Dr. Ho. In June, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that the doctors in fact did not have standing to bring the case.

James Ho glories in the nation’s culture wars. He has championed free speech since he was a student at Stanford, and he sometimes views criticism of those with whom he agrees as tantamount to censorship. In February 2022, at a Georgetown University Federalist Society event, he rose to the defense of Ilya Shapiro, then a Georgetown lecturer and a libertarian scholar who had recently tweeted that President Biden’s pledge to appoint a Black woman to the Supreme Court could lead to a “lesser Black woman” on the court. Shapiro had apologized for the comment; the school launched an investigation. Ho saw an opportunity to make a point. “If Ilya Shapiro is deserving of cancelation,” he said, “then you should go ahead and cancel me too.”

In other circumstances, however, Ho is not above doing some canceling of his own. In 2022 he announced that he would no longer accept law clerks from Yale Law School, after a couple of instances in which he felt the university didn’t do enough to prevent protesters from heckling conservative speakers, including Kristen Waggoner, the head of the ADF. “Yale not only tolerates the cancelation of views,” Ho said, “it actively practices it.” (In the wake of the announcement, Jerry Smith, the Houston judge Ho had once clerked for and a Yale graduate, called the boycott idea regrettable and let it be known that he would continue to welcome clerks from his alma mater.) Ho has since widened his boycott list to the law school at Stanford and to Columbia University, even though those most directly affected by the boycott would be the conservative students at those schools who were hoping to clerk for him.

Ho’s defiance brings to mind his mentor and former boss, Clarence Thomas, who also enjoys speaking at Federalist Society gatherings and hobnobbing with the wealthy and powerful, even as he radiates a sense of victimhood at the hands of elites. They are both men of color who have fought against affirmative action most of their lives. They’ve fought zealously against abortion rights—and won. They’re both characterized by the left as ideologues—and by the right as stalwart defenders of the Constitution. After stories by ProPublica described the lavish trips and other gifts Thomas had received from billionaire Crow—and had failed to disclose as the high court’s rules require—Ho denounced the articles as part of a political witch hunt.

Last summer, Ho himself came under fire for a conflict of interest. The news website the Lever reported that Allyson Ho had been a longtime ally of the Alliance Defending Freedom, and in the two years before the group filed its suit seeking to outlaw mifepristone, she had received at least $4,000 in honoraria for speaking at ADF events. Ho didn’t recuse himself from the case because, he told a reporter, “I consulted the judiciary’s ethics adviser prior to sitting in this case and was advised that there was no basis for recusal.”

To the left, it was another sign that Ho—like Thomas and Justice Samuel Alito, another recipient of undisclosed gifts from wealthy benefactors—was beholden to right-wing power brokers, and another blow to the public’s falling confidence in the federal court system, which is near its lowest levels in history.

Some conservatives would like nothing better than to see Ho fill the next opening on the U.S. Supreme Court. But not everyone thinks his appointment is a sure thing, even if Trump is elected. “A lot of Republicans view him as a bit of a wild card,” said a former judge. “He has an independent streak. He’s unpredictable, not viewed as a reliable.” For example, in the past two years Ho, the champion of free speech, has written a couple of opinions siding with citizens who criticized or otherwise ran afoul of the police—decisions that threatened his standing among those who want judges to offer unqualified support to cops and prosecutors.

Ho also disagrees with Trump on a key issue: birthright citizenship, the provision of the Constitution ensuring that children born in the U.S., even to undocumented immigrants, are citizens. An immigrant who came to the U.S. as an infant, Ho has been steadfast in his support of the idea. “Birthright citizenship is a constitutional right,” he wrote in 2007, referring to the Fourteenth Amendment, “no less for the children of undocumented persons than for descendants of passengers of the Mayflower.” But for those who oppose birthright citizenship, such as former Trump adviser Michael Anton, the intent of the Fourteenth Amendment was to grant citizenship to newly freed slaves—not the children of undocumented immigrants. Originalism, it seems, is in the eye of the beholder, even for conservatives.

Ho complains about conservative voices being canceled, but the truth is that his side has triumphed. Back in 1999, originalists were still battling to be taken seriously, united by a sense of nostalgia for some imagined less complicated time before the activists got hold of the Constitution and began finding rights that weren’t specifically spelled out. Twenty-five years later, the Supreme Court is reliably originalist, as is the Fifth Circuit. Abortion, one of Meese’s top priorities, is no longer recognized as a constitutional right, and regulations that protect the environment and consumers have been significantly weakened—thanks to Ho and his fellow originalists.

It’s not in Ho’s nature to declare victory, though, or to dial back his tone of embattled victimhood—not while mifepristone is still legal, the unelected bureaucrats at the EPA keep telling companies how to do business, and woke liberals run amok on college campuses. In a speech last year, Ho quoted a New Testament passage about the persecution and suffering that Christians have endured. “Being faithful to the Constitution,” he said, “is like being a faithful Christian.” Ho is a true believer, and his judicial crusade has only just begun.

This article originally appeared in the September 2024 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Our Next Supreme Court Justice?” Subscribe today.