Even people who want to use their embryos may “age out” of using them. Dalla Costa gives the example of a 48-year-old woman who undergoes IVF and creates five embryos. If the first embryo transfer happens to result in a successful pregnancy, the other four will end up in storage. Once she turns 50, this woman won’t be eligible for IVF in Italy. Her remaining embryos become stuck in limbo. “They will be stored in our biobanks forever,” says Dalla Costa.

Dalla Costa says she has “a lot of examples” of couples who separate after creating embryos together. For many of them, the stored embryos become a psychological burden. With no way of discarding them, these couples are forever connected through their cryopreserved cells. “A lot of our patients are stressed for this reason,” she says.

Earlier this year, one of Dalla Costa’s clients passed away, leaving behind the embryos she’d created with her husband. He asked the clinic to destroy them. In cases like these, Dalla Costa will contact the Italian Ministry of Health. She has never been granted permission to discard an embryo, but she hopes that highlighting cases like these might at least raise awareness about the dilemmas the country’s policies are creating for some people.

Snowflakes and embabies

In Italy, embryos have a legal status. They have protected rights and are viewed almost as children. This sentiment isn’t specific to Italy. It is shared by plenty of individuals who have been through IVF. “Some people call them ‘embabies’ or ‘freezer babies,’” says Cattapan.

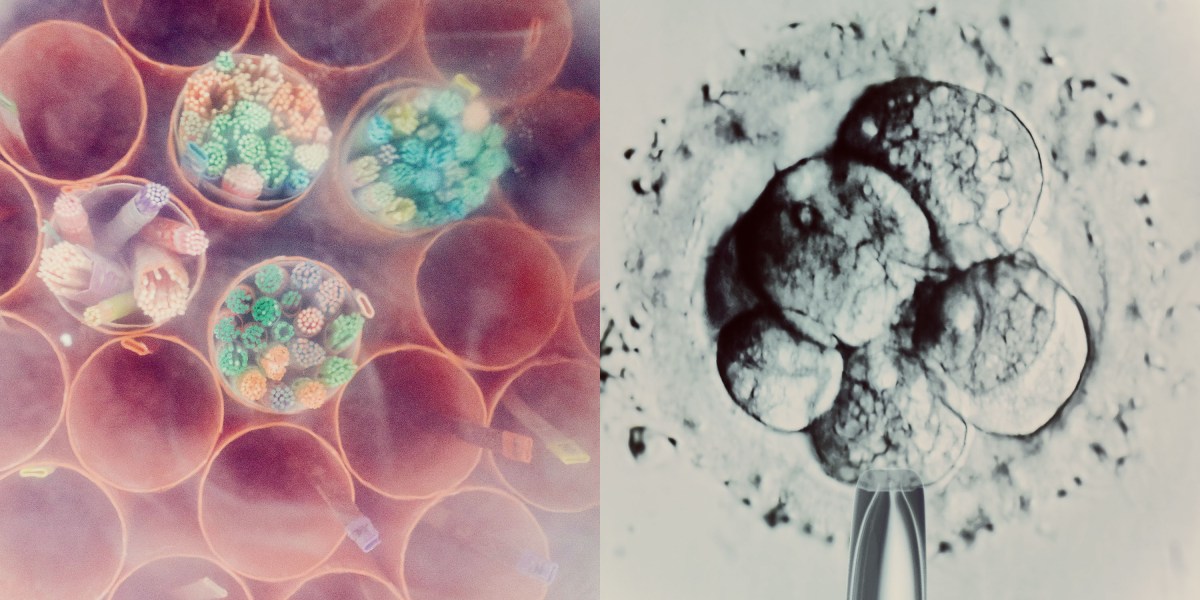

It is also shared by embryo adoption agencies in the US. Beth Button is executive director of one such program, called Snowflakes—a division of Nightlight Christian Adoptions agency, which considers cryopreserved embryos to be children, frozen in time, waiting to be born. Snowflakes matches embryo donors, or “placing families,” with recipients, termed “adopting families.” Both parties share their information and essentially get to choose who they donate to or receive from. By the end of 2024, 1,316 babies had been born through the Snowflakes embryo adoption program, says Button.

Button thinks that far too many embryos are being created in IVF labs around the US. Around 10 years ago, her agency received a donation from a couple that had around 38 leftover embryos to donate. “We really encourage [people with leftover embryos in storage] to make a decision [about their fate], even though it’s an emotional, difficult decision,” she says. “Obviously, we just try to keep [that discussion] focused on the child,” she says. “Is it better for these children to be sitting in a freezer, even though that might be easier for you, or is it better for them to have a chance to be born into a loving family? That kind of pushes them to the point where they’re ready to make that decision.”

Button and her colleagues feel especially strongly about embryos that have been in storage for a long time. These embryos are usually difficult to place, because they are thought to be of poorer quality, or less likely to successfully thaw and result in a healthy birth. The agency runs a program called Open Hearts specifically to place them, along with others that are harder to match for various reasons. People who accept one but fail to conceive are given a shot with another embryo, free of charge.

GETTY IMAGES

“We have seen perfectly healthy children born from very old embryos, [as well as] embryos that were considered such poor quality that doctors didn’t even want to transfer them,” says Button. “Right now, we have a couple who is pregnant with [an embryo] that was frozen for 30 and a half years. If that pregnancy is successful, that will be a record for us, and I think it will be a worldwide record as well.”