Ferlando Esco hasn’t been home in nearly 20 years.

The former Canton resident is serving a life sentence in Mississippi’s prisons not because he was convicted of killing or seriously hurting anyone. The 50-year-old received that sentence under the state’s habitual offender law.

That law states that two prior, separate felony convictions that resulted in a prison sentence of at least one year in state or federal prison can result in a life conviction without the possibility of parole. Only one of the felonies has to be a violent crime.

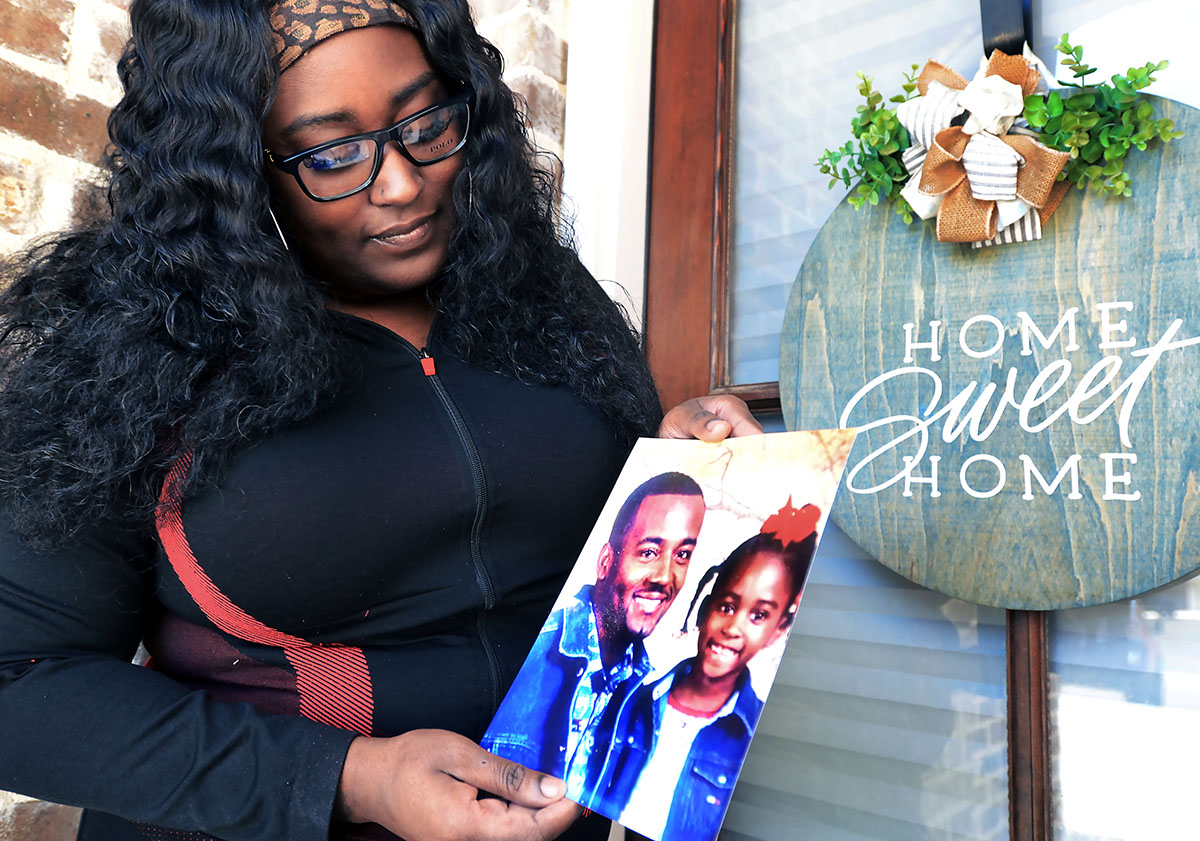

His daughter, Ferlandria Porter, 30, has been fighting for his release and is calling on the state Legislature to pass laws that give people like her father a chance at parole – a chance to come home.

“I’m still fighting and praying that the laws change, that the habitual offender law changes,” Esco said in a phone interview from a Colorado prison, where he was transferred last year and remains in the custody of the Mississippi Department of Corrections.

Porter is collecting signatures for a petition asking for changes to the habitual offender law. In the petition, she writes the state’s habitual offender law significantly affects those like Esco who committed a felony in adolescence and leaves them without hope.

Esco, who is 50, said the laws don’t recognize how he and others have matured and changed while incarcerated. He tries to help younger men when they come to prison because he sees himself in them. Esco has also taken classes that are available to him and he prays.

A 2019 report by FWD.us found that more than 2,600 people are serving prison time under Mississippi’s habitual offender laws, and nearly half have been sentenced to life or a virtual life sentence of 50 years or more. Black men are disproportionately sentenced under these laws.

Among those sentenced as habitual offenders are people serving time for nonviolent offenses, like Tameka Drummer, who went to prison in 2008 for possessing less than two ounces of marijuana. She had two prior violent felonies that she already served time for.

Porter sees a life sentence without parole as essentially a death sentence. She understands that the Parole Board, especially in recent years, is tough about its decisions, but at least people would have a chance to be released.

“Give him a chance to come home to be a grandfather,” she said.

Esco has seen how his daughter is advocating for his release and reform to the state’s habitual offender law. Visits with his grandchildren have renewed his hope of returning home, even over the years as lawmakers file reform bills and they don’t become law.

In November, Esco was transferred from Walnut Grove Correctional Facility to a prison in Colorado, according to prison records. Porter said the family was not given a reason for his move, and they hope to visit him there.

The first felony conviction on Esco’s record was a strong arm robbery from 1991 when he was 16, according to court records.

He said the habitual offender law penalized him for a mistake he made as a teenager, when his mindset made him more likely to take risks and not think about consequences.

“You don’t know that it will come back to haunt you … and that’s what happened to me,” Esco said.

The next conviction that paved the way for his sentence as a habitual offender was in 2005, when he was 30. Esco received six sentences stemming from his role in an attempted robbery in the parking lot of a McDonalds in Madison, where one man was shot. His two co-defendants pointed to Esco as the mastermind of the plot to lure the man there, according to court records.

Esco remembered being in a state of disbelief when he was sentenced to life. He said all he could think about were his young children and what would happen to them.

Porter, family members and supporters believe Esco is innocent and was wrongfully convicted in the Madison case. He maintains he was not at the McDonalds at the time of the failed robbery.

Porter has another petition laying out the details of her father’s case and calling for his release.

In his appeal and a petition for post-conviction relief, Esco argued that his co-defendants were coerced into implicating him in exchange for lesser prison sentences. He also argued that an eyewitness, a McDonald’s worker, did not identify Esco from a lineup and that evidence wasn’t presented in court, according to case records.

The Mississippi Court of Appeals rejected the arguments.

In recent years, there have been bills proposed in Mississippi to alter how people are sentenced as habitual offenders, but many of those efforts died in committee.

So far this session, Rep. Bryant Clark, D-Pickens, filed a House Bill 225 that would revise the habitual offender penalty so someone would have to have been previously convicted of two violent crimes, and they would be eligible for parole or early release consistent with the eligibility for the offenses they were sentenced to. Life sentences would be calculated at 50 years.

House Minority Leader Rep. Robert Johson III of Natchez refiled bills to make habitual offenders parole eligible (HB 572) if they serve 10 years for a sentence that is 40 years or longer and to exclude drug and nonviolent offenses when computing prior offenses (HB 570).

Rep. Jeffrey Harness, D-Fayette, refiled HB 285 to exclude nonviolent offenses from habitual offender penalties.

Last session, Senate Minority Leader Derrick Simmons of Greenville filed a series of bills, which would have changed how former convictions count toward sentencing someone as a habitual offender, including whether they were at least 18 when the crime was committed and the two prior felonies were violent crimes.

Without a law change, there aren’t many avenues for Esco to be released from prison.

He has tried to fight his case in court but that hasn’t been successful. The most recent attempt was a federal habeas petition, but it was dismissed in 2017 after going up to the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Porter said the family will look into whether her father can apply for a pardon from Gov. Tate Reeves. To date, the governor has not pardoned anyone.

“We suffer,” Porter said about how her family is affected by her father’s incarceration. “I feel like we’re being chained up, too.”