From the Spring 2025 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

In the scrubby oak landscapes of central Florida, winters are heating up, and Florida Scrub-Jays—those chatty, curious birds endemic to the Sunshine State—are being impacted in unexpected ways.

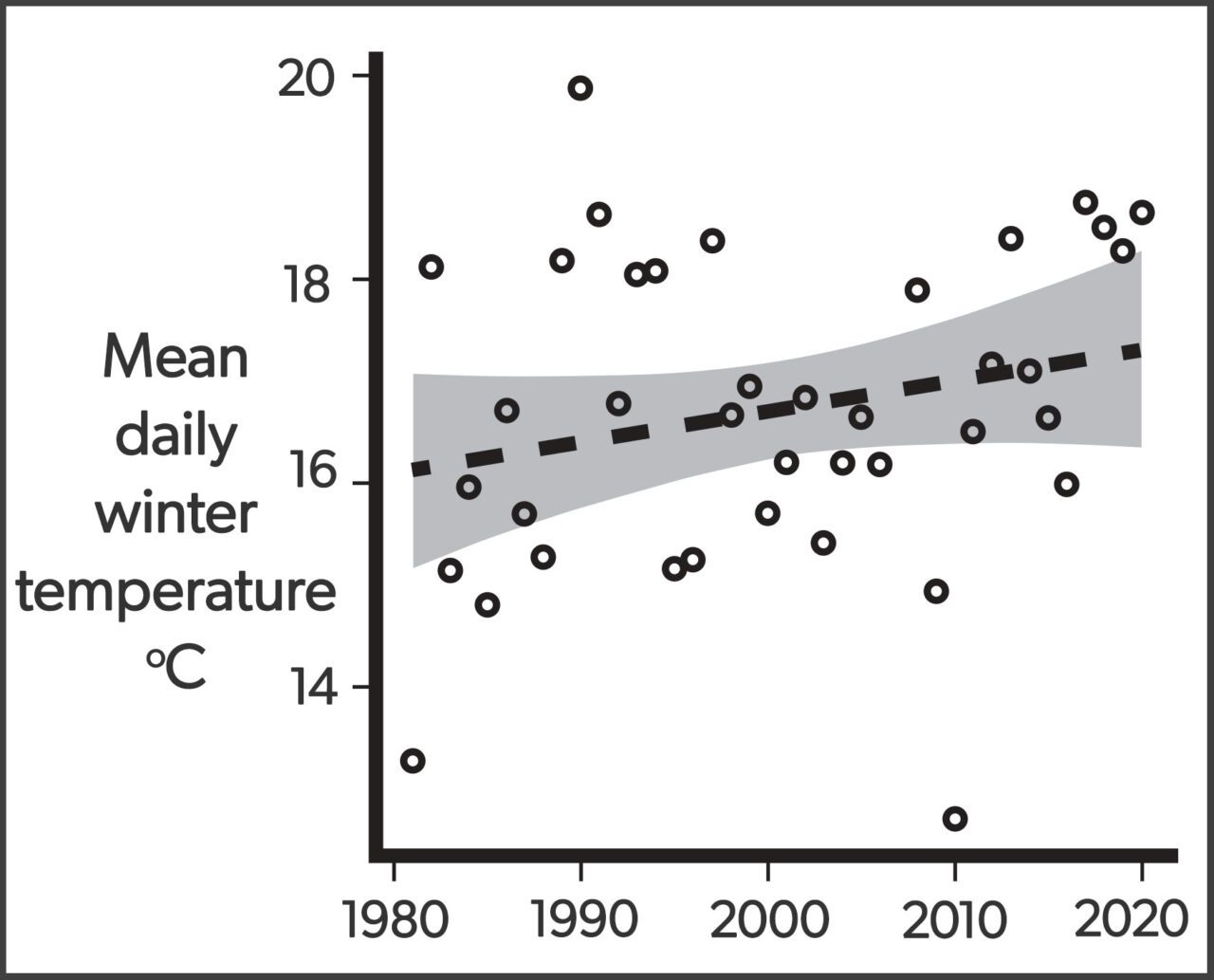

A groundbreaking 37-year study published last October in the journal Ornithology, led by researchers at the Archbold Biological Station in Florida and Cornell Lab of Ornithology, documented a concerning pattern. From 1981 to 2018, the average winter temperature measured at Archbold Biological Station increased by 2.5°F. These warmer winters resulted in Florida Scrub-Jays now nesting one week earlier than they did in 1981, according to scientists.

At first glance, earlier nesting might seem advantageous. “Generally speaking, earlier nests tend to be more successful in many bird species,” explains study coauthor John Fitzpatrick, director emeritus of the Cornell Lab. Early-breeding birds tend to acquire the best territories, giving them a leg up in producing offspring. But among Florida Scrub-Jays, the early birds are not getting the worm. A federally protected bird under the Endangered Species Act, the Florida Scrub-Jay population declined by 15% between 2011 and 2021, according to eBird Trends data, though Fitzpatrick says some local scrub-jay populations increased where scrub habitat is properly managed. Today there are fewer than 10,000 Florida Scrub-Jays left in existence, less than 10% of the historic population size.

The benefits or consequences of breeding early are dependent on a number of factors, says Robyn Bailey, a scientist who was not involved in the scrub-jay study. Bailey is project leader of the NestWatch participatory science program at the Cornell Lab, which keeps a long-term record of bird nesting data contributed by the public.

“For some species nesting in the colder parts of their range that have been affected by climate change, it might be beneficial to nest early,” says Bailey. “But for range-restricted species like the Florida Scrub-Jay, nesting early could have consequences.”

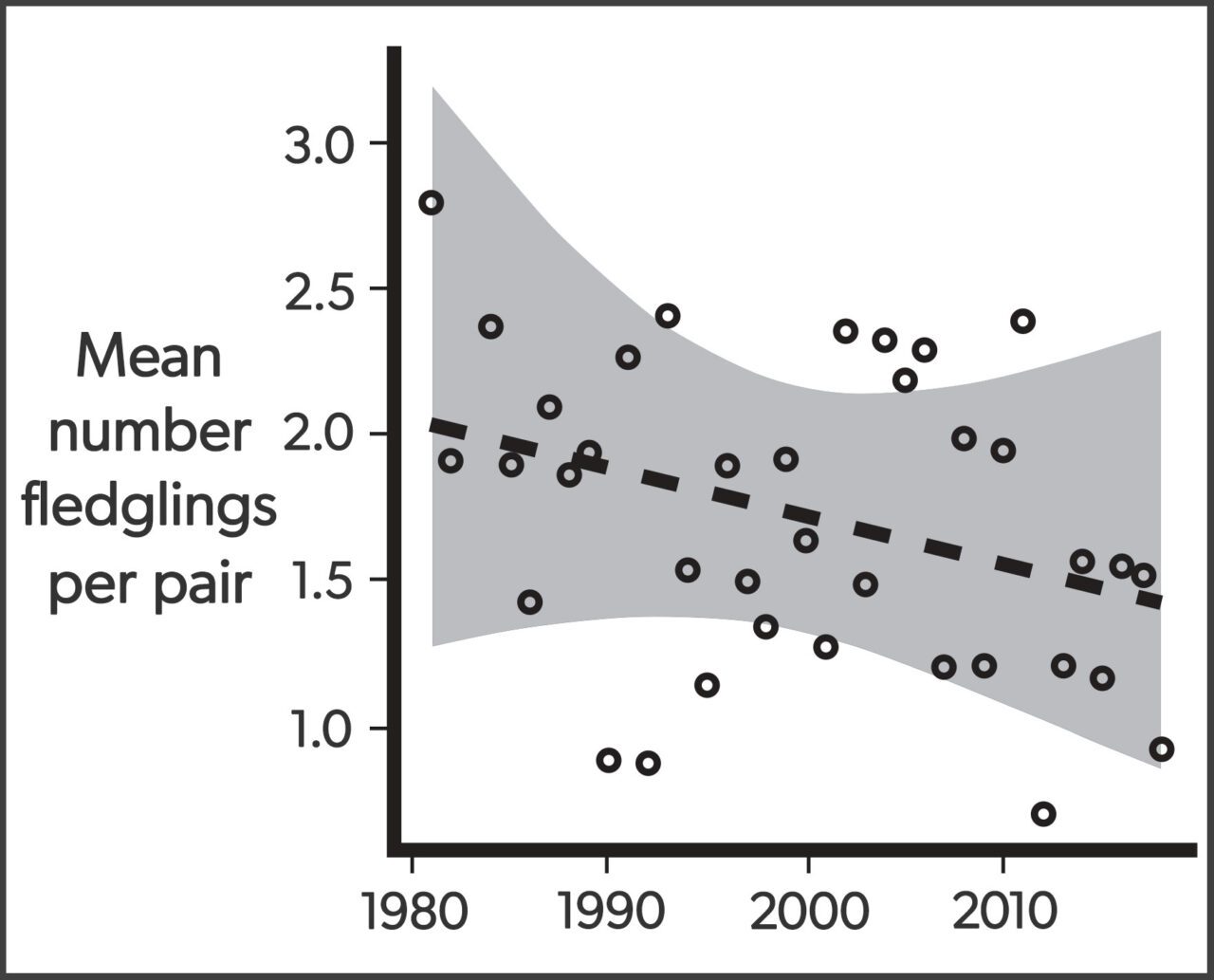

“We’re watching evolution in real time, but not in a good way,” says Fitzpatrick. “These [scrub-jays] are showing remarkable flexibility in their breeding behavior, but it’s coming at a cost we’re only beginning to understand. … Despite nesting earlier, Florida Scrub-Jay pairs actually produced fewer offspring after warmer winters.”

The numbers tell a sobering story. Warmer winters over the course of 37 years reduced the number of offspring raised annually by Florida Scrub-Jays by 25%. After nest failures during warm winters, the scrub-jay pairs built more nests (up to seven attempts in a season), which meant they laid more eggs and spent more days engaged in breeding activities.

“Think about a female scrub-jay laying up to 16 eggs in a season,” explains Sahas Barve, lead author on the study and director of avian ecology at Archbold. “Each egg weighs about 7% of her body mass. Some females are literally laying more than their own body weight in eggs during these extended breeding seasons.”

“There is a well-known trade-off between the number of breeding attempts and senescence in the bird world,” says Fitzpatrick. “The more breeding effort expended, the less likely the bird is to be alive 10 years later.”

The researchers suspect that increased predation may be one reason nests are failing. Florida Scrub-Jays typically nest close to the ground, making them vulnerable to snakes—their primary nest predators.

“There is significantly more snake activity in warmer weather,” says Barve, “so even though the jays are nesting earlier, they’re running into higher predation pressure right from the start.”

Barve says that given the additional pressures from climate change, conservation plans for the scrub-jay need to double down on the species’ primary threats of habitat loss and fragmentation.

“We need to do a better job of managing their existing habitats with fire and bringing more habitats under conservation for the species,” says Barve.

“Permanent, managed protection of every remaining patch of oak scrub is needed,” adds Fitzpatrick. “Even the seemingly insignificant, isolated patches of oak scrub can provide stepping stones for local pairs of jays to thrive and produce offspring.”

It’s not just scrub-jays that are nesting earlier. Bailey says that the Cornell Lab’s NestWatch program has documented nesting data for the past 50 years that shows that many bird species are nesting weeks earlier than they used to.

“We have reports of Eastern Bluebirds nesting in early January in Texas and Florida,” says Bailey, much earlier than their typical nesting, which starts in February in those states.

Few studies have been able to examine the consequences to overall survival when climate change alters a bird’s breeding period. In the case of the Florida Scrub-Jay, long-term data collection helped scientists quantify the costs of early nesting. Additional long-term datasets such as NestWatch are invaluable to understand how a changing environment affects birds, says Bailey.

“Researchers are using decades of NestWatch data to delve deeper into the effects of climate change,” says Bailey. “With the information we get from participants we can better understand what nesting birds are dealing with now, what they may be facing years from now, and prepare strategies to help them cope with a more variable future.”